‘Thai Stick’ or ‘Lao Stick’?

*Bolikhamsai is one of the main production centres for export ganja right across the Mekong from northern Isan (Northeast Thailand) – both sides of the river being ethnic Lao and speaking Lao anywhere outside the towns.

*

In the ‘Thai Stick’ era, nominally ‘Thai’ ganja came from north Isan and Central Laos, one of the most famous batches being Central Lao ‘Golden Voice’ – as branded by Western smugglers…

*

Cultivation across north Isan was part of a very Lao tradition of growing and smoking ganja that expanded and commercialized with the major urban centre of the region, Vientiane.

*

In Vientiane’s decadent 60s Cold War heyday, the villagers of northern Isan supplied most of the young women who were trafficked or migrated to brothels, opium palaces, and go-go bars as the Lao economy boomed during America’s anti-Communist crusade in Indochina.

*

Western money also poured into provincial Isan towns such as Udon, now once again eclipsed by Vientiane, but then profiting from a commodity that could literally fetch more than its weight in gold in the USA.

*

The close careless planting in the photo is a sign of bulk production. But now that Thailand and Laos are eyeing full legalization, the crop is set to once again realize its potential and no doubt ultimately exceed the days when it was branded by Westerners as ‘Thai Stick’.

BBC JOURNALIST NEVER TRIED THAI GANJA, FEEDS ‘SKUNK’ HYSTERIA

February 21, 2015 · by The Real Seed Company · in cannabis, CBD, drug policy, history, landraces, skunk. ·David Shukman of the BBC claims that “The weed so familiar to many of my generation was characterised by a relatively balanced amount of THC and CBD” when compared to today’s hybrid strains. This is true only of traditional hashish from regions such as Afghanistan, Morocco, Lebanon and Nepal.

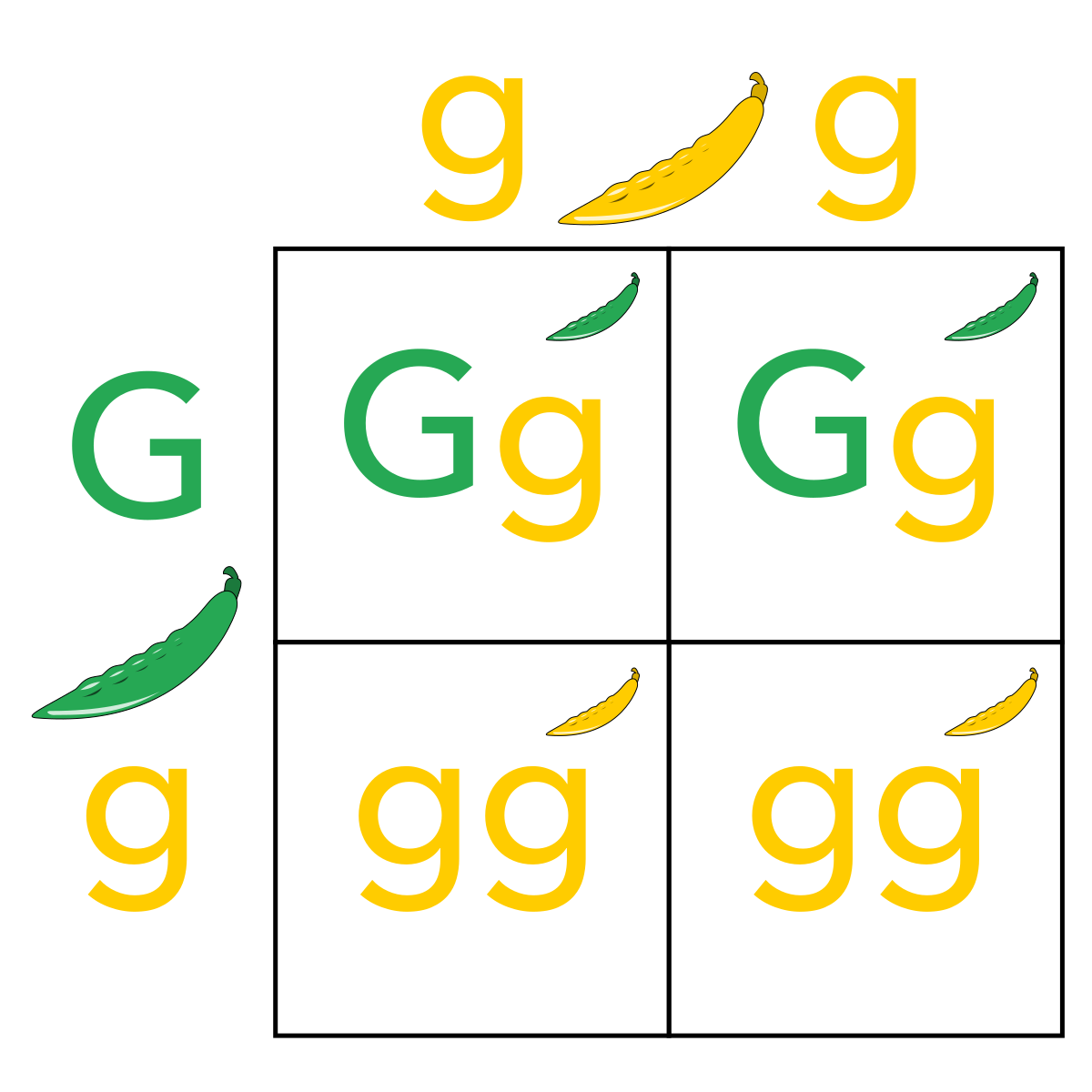

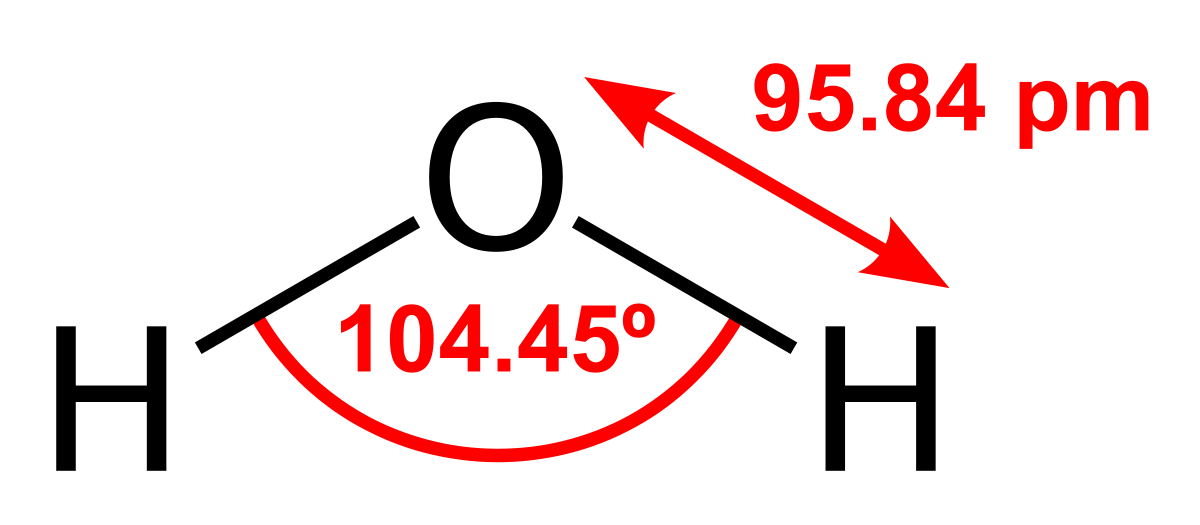

Because old-fashioned cannabis resin (‘hash’) is made from landraces which have been selected for resin production and had little selection for potency, it does indeed often exhibit something approximating a balanced 1:1 THC:CBD ratio. But even back in the ’60s and ’70s, an era in which we are told cannabis was a more innocent and far gentler plant, there was plenty of imported pot in which CBD was often more or less absent and THC levels could be very high. Typically, this took the form either of refined cannabis oil or—more usually—of high quality ganja, meaning cured unseeded or lightly seeded flowering tops from the tropics and subtropics – ‘Thai Stick’ and the like.

A traditional ganja strain flowering in Manipur, in the Indian tropics.

In Thailand, Malawi, or regions such as South India, the strains of cannabis that have been grown for centuries to produce ganja most often produce only minimal quantities of CBD and can even exhibit levels of THC comparable to those of so-called ‘skunk’. Back in the hippie heyday, such pot was given informal underground brands like ‘Swazi Red’ or ‘Colombian Gold’.

Traditional Indian ganja (‘herbal cannabis’) from Manipur, Northeast India.

In 1975 and 1976 the Laboratory of the Government Chemist reported Thai with as much as 17% THC—and that was after the bud had spent months on boats reaching England. THC levels such as this are far from unusual in Southeast Asia. In the ganja growing heartlands along the Mekong River generations of farmers have provided a continuous selective pressure for potency. Traditionally, a key part of the cannabis economy in Thailand and Laos is said to have been formed by specialists who produced high-quality seed, which was then supplied to farmers. The best of any season’s harvest would come from such fields. Similarly, in the Imphal Valley of Manipur, farmers and home growers know to keep seeds from good (i.e., potent) batches of ganja for sowing the following season. On an early collecting trip to Manipur, for example, I found a householder who only relucantly parted with seed from a standout plant. Growers who know this batch can attest to how potent the best individuals were.

A garden of ganja plants midway through harvest in Manipur, India.

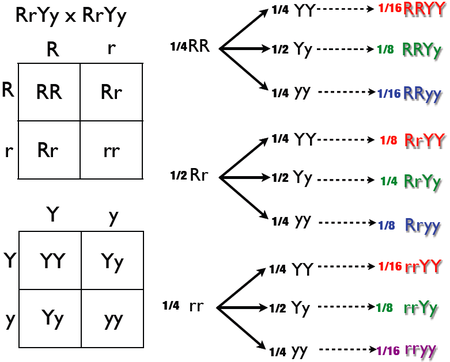

Clearly the selective pressure in traditional ganja growing is less intensive than that of the modern so-called ‘clone’ method for breeding skunk, in which selected ‘mother plants’ can be kept indefinitely under 24-hour light regimes. However, the cumulative effect over generations of traditional ganja farming can result in very strong cannabis that’s often in any meaninful sense devoid of CBD. Analysis of samples from tropical India indicates that CBD is typically absent—even in some of the milder Bengali strains. This was the case in the ’60s and remains so today. Regarding THC levels, further evidence that the potency of modern hybrids is far from unprecedented comes, once again, from British seizures. In the words of the Home Office, as recorded in Hansard:

The latest data from the Forensic Science Service Ltd (FSS) show that the average tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content of mature flowering tops from plants, otherwise known as sinsemilla, seized and submitted to the FSS from the 1 January 2008 to the present day was 14.0%. By comparison, during the same period, the average THC content of traditional imported cannabis and cannabis resin was 12.5% and 5.5% respectively.

On average, skunk (the FSS called it ‘sinsemilla’) showed only 1.5% more THC than ganja. So much for many times more potent. And, importantly, only in hashish would THC have been offset by a similar quantity of CBD.

In fairness, the BBC’s reporting on cannabis does seem to be improving. But—even if unwittingly—Aunty is still feeding the skunk hysteria.

Postscript:

Looking again at the LGC data I see that in ’78 a sample of Indian cannabis resin showed 26% THC. Customs bagged a 16% THC batch of Moroccan resin in ’75, and a shipment of Pakistani resin with the same strength in ’78. And then there are the concentrated extracts—‘hash oils’—with Indian, Kenyan and Pakistani samples all hitting around 40% THC. Simple extracts of this potency need to be made from starter material with a high cannabinoid content. The most potent was 48% THC oil from India seized in 1975. This is likely to have been prepared from tropical ganja plants rather than northern, Himalayan charas landraces.

The LGC does make the important point that “Cannabis resins normally had higher THC contents than most herbal material…”. Typically, the ‘herbal cannabis’ reaching UK shores during this era was of fairly low potency—mid to low single figures THC—either because it was from poor stock, or had degraded en route. This does, to be fair, support the kind of line Shukman is taking, though not the current media focus on CBD. Historically, ganja is most unlikely to have contained CBD in any relevant quantity. Some of the best bud to reach Britain in the ’70s appears to have been coming from southern Africa, such as Rhodesia—now Zimbabwe—with a sample hitting 12%. Nigerian and South Indian ganja seizures were milder, at 7.4% and 7.8%—less potent, but still typically without any meaningful quantity of CBD.

Manipuri ganja landrace in full flower, Imphal Valley, Northeast India

Should Thai ganja be seen as exceptional? Perhaps for this era in the UK it should, though both the proportion of samples available from seizures and ample anecdotal evidence suggest there was plenty of it about in the country, in addition to the stronger resins and concentrated oils. The LGC points out the unique appearance of the “Thai Stick” brand: “Green or brown sticks of several seedless tops tied around bamboo with a number of sticks compressed into a slab.” I’m sure there are readers who recognise this, either from having seen the real thing back in the day or on their travels.

Thai sticks, as shared on Facebook by Peter Maguire, author of Thai Stick: Surfers, Scammers, and the Untold Story of the Marijuana Trade

The LGC figures suggest that the potency of Thai seizures peaked in the early to mid ’70s, and then began to decline after the Vietnam War and the Fall of Saigon. It’s not clear whether this sample is indicative of changes at the source in Isan, Northeast Thailand. But as the authors state, in ’75 and ’76 “by far the highest quality cannabis originated in South East Asia (exclusively in the form of “Thai sticks”) and this was reflected in its street price, at least in the United Kingdom, over the same period. However, the 1978 seizures which originated in Thailand, while still prepared in the form of sticks, showed a dramatic decrease in THC level compared with previous years. A careful study of the physical appearance of seizures of Thai origin for the three years revealed an increasing seed content in the cannabis.”

To take a contrarian line, perhaps the changes that have occurred in the UK over the last two decades are about catching up to highs the market, and its consumers, had already reached in 1975.

The featured image on the homepage is via the authors of a superb new book, Thai Stick: Surfers, Scammers, and the Untold Story of the International Marijuana Trade.

Last edited: