acespicoli

Well-known member

A Farmer’s Guide to Rearing Predatory Mites La Trinidad Benguet 2007

Beverly S. Gerdeman1 and Rufino C. Garcia2

Lynell K. Tanigoshi1

1 Washington State University, USA

2 UPLB Laguna, Philippines

Basically the methods described follow two simple principles to rear predatory mites:

- leaves are stacked.

- the device is inverted.

I. Tile Method (developed by Glen Scriven and James McMurtry, UC Riverside)

Materials

- Shallow pan filled with ½ inch of water.

- 1-inch mattress foam cut to fit pan. Squeeze in water until soaked.

- Black plastic or vinyl tile cut to fit foam. Leave a narrow margin of foam exposed.

- Tissue cut to fit around the edge of the black plastic. Drape it over the edge of the foam and touch the water.

Preparation

- Place a handful of spider mite infested leaves on the black plastic.

- Place a leaf with predatory mites on the spider mite infested leaves.

Where to find a start of predatory mites

(We are using Neoseiulus longispinosus.)- Search abandoned strawberry fields.

- Look for poinsettia leaves infested with spider mites.

- Look for spider mite infested cassava leaves.

Maintenance

There is no exact schedule for maintenance. It depends on the rearing method you choose, where you place your colony and the weather. How often you add food depends on the number of predatory mites you begin with and how many spider mites you feed them.- Maintain correct water level.

- If only a few live spider mites remain, add more infested leaves.

- Keep leaves in the center of the tile or plastic, to prevent moldy leaves.

- Remove moldy leaves.

Release

(Refers to all the rearing methods presented.)- When you can see predators on every leaf

- When you see only a few live spider mites on each leaf.

II. Clay Pot Method (developed by Carl Shanks, Washington State University)

Materials

- Two shallow clay pots (you may use a single pot if you prefer).

- One shallow basin large enough to hold the clay pots

Preparation

- Wet but don’t soak the pots in water.

- Invert one pot in the basin.

- Fill the basin so that the water comes up to the middle of the pot.

- Place a handful of spider mite infested on the clay pot.

- Place a start of predators on the leaves.

Maintenance

- Maintain proper water level.

- Remove moldy/black leaves.

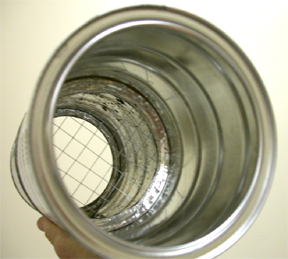

III. Can Method (developed by Lynell K. Tanigoshi, Washington State University)

Materials

- Two cans with plastic snap-top lids (such as cans containing powdered milk for infants)

- small amount of chickenwire

- elastomeric sealant

Construction

- Cut out the bottom of the cans leaving a narrow ledge.

- Cut a circle of chicken wire to fit between the two cans.

- Run a bead of sealant along the ledge of one can and press the chickenwire in place.

- Run a bead of sealant along the ledge of the other can and press the two cans together.

- Run a bead of sealant outside where the cans join, to seal any gaps between the cans.

- Allow to air dry before using.

- Cut a hole in each snap-top lid and glue in a 120 mesh silkscreen window for ventilation.

Preparation

- Fill one side of the can with dry, spider mite infested strawberry leaves.

- Set the cans upright with the leaves in the upper can.

- Place a start of predators inside the upper can with the spider mite infested leaves.

- Snap both lids on the cans.

Maintenance and Use

- Check for moisture inside the cans. Dry them out.

- If fungus develops in the can or on the leaves, clean it out and start all over.

- When only a few live spider mites remain, fill the lower can with spider mite infested leaves and invert so the new leaves are now in the upper can (do not remove the old leaves yet).

- When there are only a few live spider mites in the upper can, invert and remove the oldest leaves (now in the upper can) and replace with fresh spider mite infested leaves.

- Repeat until you can see at least one predator on each leaf and there are few spider mites.

IV. Bag Method (developed by Beverly S. Gerdeman, Washington State University and Rufino C. Garcia, UPLB)

Materials

You can sew any size but remember—the larger the bag, the farther the mites have to crawl to reach the fresh leaves.

- Silkscreen (at least 120 mesh)

- Netting

- Two bamboo sticks or flat Plexiglas strips. The length should match the width of your tube.

- Two hangers

Construction

- Sew the silkscreen into a tube. (Be careful and do not make any unnecessary holes with the needle or the predatory mites will escape.)

- Cut a circle of netting and sew inside the tube, dividing it into two equal halves.

How to Use

- Place spider mite infested leaves in one side of the bag.

- To close, roll the silkscreen ends of the bag on a bamboo stick and hang the bag in a shady, warm spot protected from rain.

- Check leaves and when only a few live spider mites remain, place new spider mite infested leaves in the empty side of the bag and invert but do not discard the old leaves yet because they contain eggs which haven’t hatched yet. (Remember, new leaves are always in the top portion of the can).

- When few live spider mites remain on the newest set of leaves, invert the bag, now remove the old leaves and fill the top portion with fresh spider mite infested leaves.

- Repeat the process, until you can see at least one predator on each leaf and only a few live spider mites remain.

Abstract: Coccinella novemnotata L., the ninespotted lady beetle, and Coccinella transversoguttata richardsoni Brown,

the transverse lady beetle, are predatory species whose abundance has declined significantly over the last few decades in

North America. An ex situ system for continuously rearing these two beetles is described here to aid conservation efforts

and facilitate studies aimed at determining factors in their decline and possible recovery. All rearing of lady beetles was

conducted in the laboratory at or near room temperatures and 16:8 L

each reared separately, and different life stages were handled independently. Eggs were collected every 1 to 2 d and

placed in holding containers, and individual clutches were transferred to cages with prey when their eggs began to hatch.

Neonate larvae were fed live bird cherry-oat aphids [Rhopalosiphum padi (L.)] for 3 to 4 d, and second instars were trans-

ferred to different cages and fed live pea aphids [Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris)]. Third and fourth instars were also fed pea

aphids, but reared individually in small cups to preclude cannibalism. Upon pupation, individuals were collectively trans-

ferred to fresh cups and placed in a different container for the duration of pupation. Newly emerged adults were collected

within containers about 2 d after eclosion. Adults were housed in cages stocked with live pea aphids, supplemental food,

and rumpled paper towels as oviposition substrate. Over 80% of egg clutches were deposited by beetles on rumpled paper

towels versus other surfaces within cages, and incidence of cannibalism of egg clutches was greatly reduced on rumpled

paper towels. Techniques for successful rearing of these two coccinellids and future research regarding adaptations to fur-

ther optimize their rearing methods are discussed.

Keywords: Coccinella novemnotata, Coccinella transversoguttata, Coccinella septempunctata, bird cherry-oat aphid, pea

aphid, insect conservation.