Eltitoguay

Well-known member

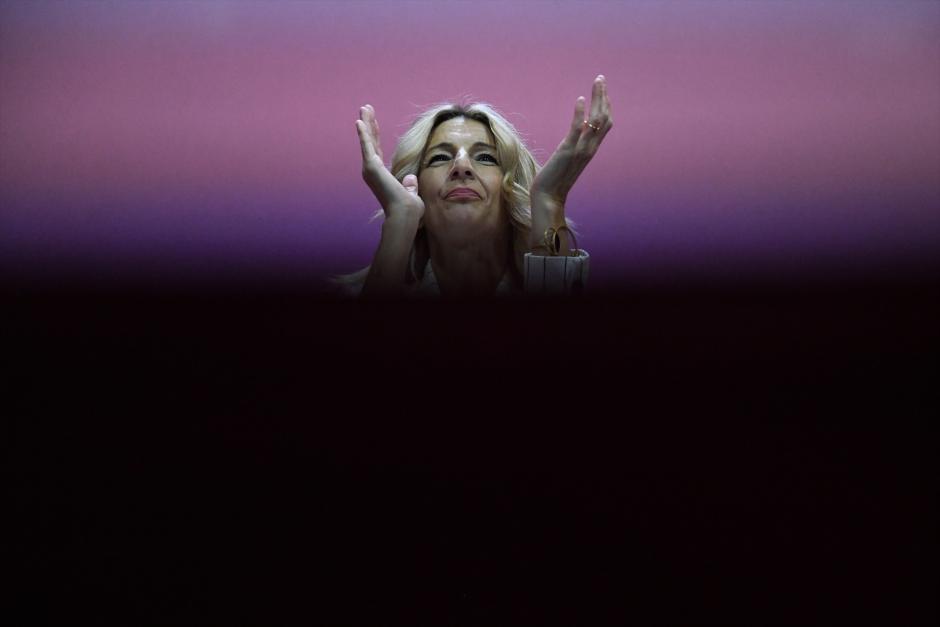

Yolanda Diaz, the Communist Vice-President of the Spanish government and Minister of Labor and Social Economy :

Yolanda Díaz - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

es.wikipedia.org

Yolanda Díaz - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

Second Vice President of the Government and leader of Sumar, Yolanda Díaz;

Social-communist government.

Yolanda Díaz expresses her communist activism: “The capitalist system is leading us to disaster”

The leader of Sumar has also stated that "there is no room for free women in the country of the masculinity of Mr. Feijóo (right, Popular Party) and Abascal (ultraright, VOX) "

Ramiro Fdez-Chillon

Madrid 01/14/2024

The Vice President of the Government and leader of Sumar, Yolanda Díaz –affiliated to the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) since 1986– has stated during a rally of the 'magenta' party that «the very inertia of the capitalist economic system takes us and leads us to disaster ; because this is where we are going, to environmental disaster, and to disaster for lives ».

THE PROFILE:

Yoli's blonde hair, Iglesias' best trophy

View attachment 19058469

Mayte Alcaraz

This is what Díaz said at a Sumar rally in Madrid, where, in economic matters, she also pointed out that "democracy has to reach the economy, without a doubt, and the jobs. It should really be the public thing that decides the economic reasons of our country, and it would be a serious attack and risk if, as has happened for a long time, they were the ones that governed the economic destiny ."

Sumar leader and Second Vice President and Minister of Labor and Social Economy, Yolanda Díaz, during a Sumar EP event

Regarding social policies, the vice president has indicated –in an unclear manner– that “if we know how to leave something behind it is the domination of women , their lack of freedom, but also the lack of freedom that implies for men a form of masculinity that is accompanied by the obligation to dominate women, a form of masculinity that we do not share, which we have seen in the Madrid Assembly with Mr. Smith attacking our colleague Edu Rubiño , who is with us today (sic)”. “There is no room for free women in the country of Mr. Feijóo(P.P.) and Abascal’s (VOX) masculinity” , she added.

Ortega Smith says he does not apologize for his conduct in the Plenary because there is a "double standard" with Vox

View attachment 19058472

The Debate

Evaluating Yolanda Díaz's management

By Luis Molina Temboury | March 14, 2022

Yolanda Díaz - Wikipedia

Communist Party of Spain - Wikipedia

Sumar (electoral platform) - Wikipedia

In his book A People Betrayed , historian Paul Preston explains, with a wealth of episodes, that during the last century and a half the Spanish elites have been an obstacle to progress due to their corruption and ineptitude. And that this unfortunate attitude has caused serious social problems that the same elites have tried to resolve through repression, sometimes using extreme violence.

The bloody Franco dictatorship (Preston provides extensive documentation on this in other books) was a period of intense exercise of both baseness, although the arrival of the Opus Dei technocrats significantly reduced the level of ineptitude. Ineptitude diminished rapidly after the new democratic consensus, but with niches of dramatic growth, as during the long gestation of the financial-real estate bubble, whose responsible watchdogs did not want or did not know how to see in the data that they sang for soleares. The consequence was that, once again, many at the bottom paid the price for the ineptitude or corruption of a few at the top, in addition to suffering in their ears the tiresome sermon of collective responsibility. The real culprits got off scot-free this time, always so flamenco, and they got away with it, advising painful measures that they would not suffer. A classic.

Corruption, which during Franco's regime remained at stratospheric levels thanks to an extensive collaborative network between economic and political power, struggled to remain rooted after the Transition. Like incompetence, both vices know how to protect and succeed each other well through a network of complicit silence, if not mafia-like practices, which delays the true knowledge of History. It took us many years to learn of the foundational and endemic corrupt nature of the PP, we are still in it, of the adventures of Pujol, the protégé on the left and right to obtain political gain, or of some in the PSOE, whose practices were metastasizing throughout Andalusia. The process of knowing the truth is even slower at the top of the State, the latest episode with a King Emeritus who was once exemplary and now silent, enjoying his dark fortune as if nothing had happened... in the happy company of kings and princes like him.

Looking at the glass half full, it can be said that, although with exasperating delay, the corruption and ineptitude of the elites has diminished considerably due to the denunciation of the press and the action of justice, although the Spanish people continue to watch brand new chapters, waiting for explanations and apologies that take a long time to arrive and putting up with the denial of the obvious, the complicit silence or the you more of the politicians.

Social dialogue

In civilized countries, and following the recommendations of international organizations, the ideal is that labor issues are resolved by consensus through social dialogue between the two parties in a potential conflict: representatives of employers and workers. It is evident that this system favors social peace and progress, so the role of politicians should be to encourage and bless with the norm the possible consensus.

Spain is a country where social dialogue has been improving and is currently working reasonably well. One only has to see the patience and responsibility of union representatives in moderating their demands in crisis situations or the concessions of employers to achieve a consensus favourable to workers when the economy improves, as has happened with the latest labour reform.

The problem arises when politicians in the style described by Preston and the usual elites, turning on their media loudspeakers, instead of celebrating agreements, position themselves against one of the parties, mainly the workers, in order to dynamite the dialogue. Take for example what happened with the increases in the minimum wage to which I referred in this article , an issue in which the mercenary ideologues of the big companies disguised as technical economists, the neoliberals accustomed to lying as an argument, on this occasion accompanied by other technicians from intermediary companies whose activity consists precisely in squeezing workers who receive the minimum wage, or the Governor of the Bank of Spain and his experts, systematically positioned against the workers, do not cease to proclaim misfortunes for the increases in the minimum wage, even though they contradict the evidence of the data.

For those who think that the consensus on minimum wage increases is broken by the employers' association, which has done nothing but give in to the powerful media avalanche and then join in, it should be remembered that, in July 2018, within the framework of the IV Agreement for Employment and Collective Bargaining, the employers' association and the unions reached an agreement to increase the minimum wage to 1,000 euros in 14 instalments in 2020. That is exactly the scandalous and dangerous figure now set by the Government in 2022, with the approval of the unions, but now without the employers' association, at the end of a pandemic that has mainly affected workers with the lowest salaries and with a record number of employed workers, to the discredit of those who deny the beneficial effects of the increases.

It is no coincidence that the CEOE president is now demanding that electricity prices not be affected by the rise in gas prices, nor that his opinion coincides with the offensive of the electricity lobby, perhaps even more powerful than the banking lobby, which has brought its “prestigious technical economists” out of their austerity -seeking hiding place to urgently defend the same nonsense in the media. The businessmen who suffer from the brutal rise in electricity prices, whose utility consists in fattening the obscene profits of the large electricity companies at the cost of the collapse of many energy-consuming companies, must have been amazed by the opinion of their president, but it seems that where there is a captain, the sailor does not command.

The processing of labor reform

The passage of the latest labour reform through Congress was an episode that should be included as an appendix in a possible reissue of Preston's book, as it clearly confirms his arguments. It is rare to witness an open-chested battle between the corrupt and inept against the hard-working Spanish people, although the recent crisis of the PP could suggest that we are facing a new cycle in which both defects, to the greater astonishment of the audience, shamelessly air their differences in public.

For the processing of the latest reform, an unprecedented pact in which workers gain rights, this time the best allies were available. The document had been agreed upon, in an exercise of tenacity and patience by the Minister of Labour (you can see where the title is going), between a modern employers' association determined to leave behind the years of entrenchment and some corrupt prisoners and majority unions aware that it is better to consolidate something less than to go back much further later due to a probable revengeful change of the norm.

The three parties had previously been the protagonists of a greater feat, when they agreed to avoid layoffs in the face of the massive cessation of work activity due to COVID-19. The cruel nightmare that we would have had to endure if they had not agreed to support millions of families by resorting to ERTES can be imagined from the data in graph G.1 below. For now, hats off!

After having saved jobs in the face of the greatest labour crisis since the post-war period and then having held out at the negotiating table to design a better future for the people, one could begin to think of a well-deserved monument to the protagonists and collaborators who had made the new reform possible, but... not so fast, the approval of Congress was still missing. Some optimists, blinded by the success of the negotiation and fleetingly forgetting that stepmother Spain prone to bringing out its two demons, glimpsed a broad consensus, but the story would be different, more realistic and traditional.

In a Dalinian-Berlangian exercise, inept and/or corrupt deputies burst in to make Spanish history again. Needless to say, the Francoist extreme right was in favor of boycotting the law: the worse, the better. The right of the PP yearned for its previous law excluding unions, so its deputies would not give in either, even if the new law was signed by the businessmen. Nor would the patriotic separatists on one side or the other, who, confident that others would get involved for them, once again made use of their nationalist blinkers so as not to see the working people on either side and to demonstrate once again their power to annoy. The deputies of the dying Ciudadanos party offered to lend a hand, thank goodness, but it was still not enough to guarantee approval. A couple more votes had to be added, which were desperately sought from the two UPN deputies, the coalition with Ciudadanos and the PP of the Navarrese regionalists, who, by exchanging a few cards, finally joined the task, again, thank goodness, just barely. But there was still another but. Just at the time of the vote, both deputies suffered a fit of ineptitude, corruption or perhaps a combination, and surprisingly voted the opposite of what they had promised. The Spanish people were once again stunned to witness a reissue of the “tamayazo”, which condemned the people of Madrid to decades of unbridled corruption, this time on a national scale and in the Congress of Deputies.

Had it not been for the hand of God, like that of Maradona for the Argentines in that football World Cup, materialized this time in the finger of a PP deputy who insisted on repeatedly clicking on the option he did not want, the Spanish people would have seen once again that history repeats itself, the social agents who architected the reform would have been left with nothing after so many months of effort, and it is likely that the minister would have thrown in the towel in the face of such nonsense, causing an unnecessary political crisis in the midst of the economic crisis caused by the pandemic and on the verge of another that would come from Putin's war.

Employment management by the 2nd Vice President and Minister of Labour

Let us now turn to the history of data. Some insist that past data with “adjusted simulations” provide better conclusions than the known data of the present. This magical method, capable of fulfilling wishes, was widely used by the representatives of the men in black after the bubble crisis, who defended the disastrous results of their wage devaluation policies with the argument that, according to their complex models, if these measures had not been applied, the data would have been worse.

Although I love science fiction, when it comes to evaluating political action I prefer to avoid time travel, which is even more mind-blowing if it is backwards, and to rely on published statistical data. This is what I did in this article , which verified the disproportionate temporary nature of employment in Spain compared to the EU with data published by EUROSTAT, or in this other one mentioned above , in which I explained that according to official Spanish statistics on the labour market, increases in the minimum wage have not destroyed employment in Spain, but have created it in all areas where there are rumours or simulations of something else.

To answer the question in the title, we have statistical series that stand out for their immediacy, such as those on Social Security affiliation or summaries of registered unemployment and contracts, which can be known just a couple of days after the end of the month and which have the advantage of being mandatory administrative records. Either you are or you are not, without sampling or mathematical complexities.

The first verification chart, which condenses more than fifteen years of employment history, represents the evolution of employment according to Social Security affiliation data between January 2007 and February 2022.

In G.1, it can be seen that the peak of employment during the financial-real estate bubble occurred in July 2007, when 19,493,050 members were registered according to the monthly average of the daily data. During the PSOE Government, the bubble burst, causing an abrupt fall in employment in construction that dragged down employment in industry and, to a lesser extent, in services. The fall in employment continued to a minimum of 16,150,747 members in February 2013.

Only since 2014 did employment begin to rise steadily, until 2019, shortly before the outbreak of the pandemic, when it recovered the maximum level of the bubble, no less than twelve years later, but having generated a bigger problem. The excessive and chronic temporary nature of employment worsened with the labour reform of 2012, and the growth of inequality due to wage devaluation added a new distinctive scourge to Spain in the European tail end: an alarming level of job insecurity and poverty.

Redirecting labour regulations that had driven a significant percentage of well-educated young people from Spain, that had condemned 30% of the population to precarious employment, that had been driving unsustainable pockets of child poverty even in households with workers in employment, that, in short, had been increasing an inequality that not only hampered the progress of the people, but also the economy itself, which had become a jammed machine that sucked wealth upwards and distributed poverty downwards, was a major challenge for whoever was going to pilot labour policy in the apparently fragile coalition government.

Minister Yolanda Díaz arrived at the Ministry of Labour in January 2020, but her first task was not to develop the regulatory reform to alleviate temporary and precarious employment because the pandemic broke out. As has been said, the mandatory confinement left millions of workers without activity, which threatened a tremendous wave of layoffs that was saved by using the ERTES, an old resource that appeared in a 1995 regulation that was modified several times, the last in the PP's labour reform in February 2012. Nobody had foreseen that the ERTES would serve to save a crisis of these proportions, so many economists celebrate the firm and rapid decision of the Sánchez Government and the willingness of the social partners to use this resource and save people before the bills, a 180-degree turn with respect to the previous sad and failed labour policy.

The new policy proved to be a resounding success, saving thousands of companies and millions of working-class families from ruin. In February 2022, 19,694,272 average Social Security affiliates were registered, the ninth consecutive monthly historical record, unexpectedly recorded two years after the greatest labour crisis since the post-war period. In those two years, the labour market has absorbed and recovered 4.7 million jobs, 3.5 million that were inactive in a situation of ERTE and an additional 1.2 million that were lost in the crisis. These data already seem sufficient to highlight Yolanda Díaz's aptitude at the head of the Ministry of Labour and to establish her provisional position in the best history of Spain yet to be written, but let's continue.

To better visualise what has happened, G.2 represents the variations in the monthly affiliation data compared to the same period of the previous year, which cushion the sawtooth of the employment curve in G.1, significant of this exceptional rate of Spanish temporary employment that disproportionately creates and destroys employment depending on the month of the year.

In G.2 it is clearly seen that the recovery of employment after the explosion of the real estate bubble took no less than six years, until 2014, when after its initial sharp decline, employment was recovering under the Zapatero government, but the "inevitable" austerity policy imposed by Brussels even before the arrival of the PP in December 2011 brought it down again, causing a second enormous accumulated pocket of destruction that was reflected in an unemployment rate that reached almost 27% in the first quarter of 2013. An unusual figure.

It is also clear that since 2014, when the sadistic measures applied to people to save the numbers of finances whose loss of control had caused the crisis culminated, employment has picked up speed, one would say not because of the measures but in spite of them, when the torture hit rock bottom. After the new sharp collapse of employment due to the pandemic, managed in a spectacularly effective manner with the use of ERTES, employment has taken off again with a force never seen before and also on an increasing trend.

But, as has been said, the minister's objective upon her arrival at the ministry had not been to solve the unforeseeable employment crisis caused by COVID-19, but rather the problem of temporary and precarious employment, for which the labour reform was designed. Once it has come into force, it is time to verify with data whether it is being effective.

The Minister's management of excessive temporary and precarious employment

In order to assess the reduction in the temporary employment rate that the labour reform aims for, the EPA for the next few quarters will have to be consulted. A semester would begin to give good clues and a year should be enough to draw conclusions. Regarding the reduction in precariousness, we will have to wait a long time. The Survey of Living Conditions, the Annual Survey of Salary Structure, the Decile of Salaries in Main Employment or the statistics of the Tax Agency will still take a year and a half or more to give a definitive answer. In the meantime, we will have to draw on other statistics with less lag that can give good clues, such as the SEPE statistics on employment contracts, whose series are handled below.

In G.3, the employment and contract series have been represented in the form of indices, taking as a starting point the period before the first crisis (January 2007) and using twelve-term moving averages. Moving averages are a simple statistical tool that consists of representing the data of a period as the average of that period and other previous ones, in this case the previous 11 months plus the current one, to cushion the fluctuations, which, being extreme in the case of contracts, make it difficult to visualise trends. In these smoothed curves it is clearly observed that after the bubble crisis, labour contracts decreased sharply, that they began to recover with the Zapatero Government, but that with the aforementioned turn of the screw due to austerity during the PP mandate they fell again. From 2013, hiring was encouraged, with a spectacular rise that for a bad analyst would be very good news, but it is not for someone who knows the abnormal behaviour of Spain with respect to the EU (again the article on temporality ).

It is not good news for employment that the number of contracts increases sharply if there are many of them of short or very short duration that are frequently terminated, which had been happening for almost 40 years before the last reform. It is not worth celebrating that many chickens enter the coop (contracts, in this case) without checking that they are not leaving through another channel. So the explosion in hiring after the 2012 labour reform was not good news. It was, of course, that employment increased, but it left as a consequence this new increase in temporary employment, chronically very high, and that precariousness soared, due to excessive labour rotation which, added to the policy of wage devaluation, mortgaged the life plans of a large portion of Spanish workers.

The comparison in the months of February represented in G.4 (the monthly fluctuation is very high, so it is advisable to compare the same months) shows that at the beginning of the recovery in 2014 the contracts had decreased compared to the times of the bubble (1.1 million in total vs. 1.4 million then) and in a greater proportion the permanent ones. In February 2007 the permanent contracts were 12.5% of the contracts and in February 2014 9%, a symptom of worsening, not so much because there were fewer contracts, as has been commented, but because the temporary nature of the contracts, which was chronically high, increased.

February 2007, in the midst of the bubble, was not a month in which temporary employment was low. The chronic defect of the Spanish labour market that had been dragging on since 1986, a very high rate of temporary employment, remained between 1992 and 2006 at around 34%, more than 20 pp. above the average rate in the EU. In February 2020, the rate differential had fallen, standing at 13 pp. above, but still double the European rate. If the rate was then lower than in the times of the bubble, it was not because of a policy that sought to achieve it, since it had been growing after the PP's labour reform, but because of the very dynamics of the excess of temporary employment in Spain, with a disproportionate destruction of temporary employment in crises, and a greater creation of temporary employment in recovery cycles. The PP's labour reform did not correct this defect, but rather enhanced it, sharpening labour turnover.

The effects of the PP's labour reform would be noticeable in that temporary contracts rose sharply. In February 2020, just before the pandemic, there were 420,000 more monthly temporary contracts than at the beginning of the recovery, in February 2014. The number of permanent contracts was similar to that of the bubble times, 180,000, but their weight in the total number of contracts was lower, due to the greater number of contracts (11.1% in February 2020 vs. 12.5% in February 2007). The hiring situation was therefore very bad before the pandemic, when the first coalition government came into being.

After two years of Yolanda Díaz's management (between February 2020 and February 2022), with employment at record levels after overcoming its biggest drop, temporary contracts have fallen significantly (by around 300,000) and permanent contracts have risen (140,000), which is good news in both senses, which can be summed up by the fact that the proportion of permanent contracts out of the total number of contracts in February 2022 was 21.9%, a figure never seen before in the entire historical series.

The SEPE data also allow us to check the evolution of temporary contracts according to their duration, which is represented in G.5. The first thing that draws attention in this graph is the large portion of temporary contracts of indefinite duration, which should decrease considerably after the latest labour reform, which has repealed contracts for work or service, in which the time was not previously fixed.

But the most striking thing by far in G.5 is the increase in the percentage of contracts lasting one week or less, which went from representing 13.6% of all contracts in February 2007 to 27.2%, exactly double, thirteen years later; from 191,805 contracts, a figure that was already very high at the time, to 433,874, an incredible magnitude. Before the last labour reform in Spain, a huge volume of temporary contracts were signed each month, 1.42 million in February 2020, and of these, 30.6% were very short-term. Another serious partial problem to be solved when the portfolio in the Ministry of Labour changed.

Since Yolanda Díaz arrived at the Ministry until two years later, with the pandemic in decline, temporary contracts as a whole fell by 20.4%, and those of seven days or less duration by 37.8%. With record levels of employment. Compared to the time when employment began to recover, in 2014, temporary contracts have deflated much of the excess generated by the PP's 2012 labor reform, but with a very significant difference: in February 2014 the average number of Social Security affiliates was 16,212,304, while in February 2022 there were 19,694,272, three and a half million more employed people.

An early indicator of the effects of the labour reform on the temporary employment rate, which will be provided by the official quarterly EPA, can be observed by observing the monthly evolution of the percentage of permanent contracts out of the total, which is represented in G.6.

A clear indication that the reform is having immediate effects is that this proportion (blue line) jumped in January 2022 to 15%, to continue its progression in February 2022 to a historic 22%.

Given that the fluctuations are very marked throughout the series, and even more so after the entry into force of the latest reform, another interesting series to observe in the coming months will be the 12-term moving average. In this smoothed curve, represented in red in the graph, it is clearly observed that after the worst of the pandemic, the proportion of permanent contracts has a very upward trend, which will foreseeably be reflected in an improvement in the temporary nature of employment in the next EPA data.

And to finish with the verifications on the data, graph G.7 represents the long series, from before the bubble, of the evolution of monthly temporary contracts according to their duration, leading monthly indicators that can also give good clues about the foreseeable results in the medium and long term of the labour reform.

The data on contracts broken down by duration are not published two days after the end of the month, like the monthly summaries. They take a few more days, but in any case they allow early monitoring of the possible effects of the labour reform. The data for February 2022 were published on 11 March.

The graph shows the explosion of very short-term contracts (seven days or less) following the PP's labour reform, and the evolution of permanent contracts, the other largest volume of monthly contracts (see G.5), which corresponds mainly to work and service contracts, which should fall considerably from April with the new reform.

For the moment, in view of G.7, it can be anticipated that even before the reform, presumably due to a reinforcement of the fraud inspection work in this type of contract, positive results were perceived in the case of open-ended contracts, which registered a monthly downward trend with a record level of employment. And positive results were also recorded in very short-term contracts, 7 days or less, which, although with an upward trend after the pandemic, still maintained a level much lower than two years earlier with a higher level of employment. In February 2022, the series of moving averages of very short-term contracts shows a stabilization, which is also a very good sign, which will have to be followed in the coming months.

Summary

Yolanda Díaz's management at the head of the Ministry of Labour and Social Economy has been of monumental excellence.

From her ministry, the collapse of employment during the COVID-19 crisis was avoided, which rose in a surprisingly short time to historic levels; avant-garde regulations have been approved, even at an international level, such as the rider law , or urgent, such as the teleworking law; the reduction of inequality among the most vulnerable workers has been pushed by defending and applying increases in the minimum wage; social dialogue and collective bargaining have been successfully promoted and precariousness in hiring has been reduced even before the regulatory change of the labour reform. Since it came into force, the data, just a couple of months later, indicate that the reform will mark a before and after in the fight against job insecurity and excessive temporary employment.

The minister's merit is all the more remarkable for having had to face a powerful gang of politicians who, for their own personal interests, have positioned themselves against a historic social pact between the representatives of workers and employers. She has demonstrated that she has baraka (this cannot be verified with data, but rather indicatively by facts) by miraculously overcoming a corrupt political intrigue expressly designed to overthrow the reform and remove her from office. And she has also overcome stubborn resistance within her own ranks, obtaining the unanimity of that part of the left that does not conceive the regulatory framework of the labour market as a constructive place for dialogue and consensus, but as a disorderly field of normative revenge.

Corollary

Although in Spanish politics it is not well-regarded that someone at the top makes an effort and makes things better for people (see the atmosphere in the Congress of Deputies against the Sánchez Government before, during and after the pandemic), the case of the management of Minister Yolanda Díaz at the head of the Ministry of Labor is worthy of highlighting, thanking and celebrating.

Here's a toast to her from someone who is not a member of any party.

Let us hope that the minister will have the opportunity to continue to manage the foreseeable negative effects on the labour market of the terrible war that is ravaging Europe so well. The protection of workers and employers against the fluctuations in prices and supplies or the labour integration of refugees will give her the opportunity to once again demonstrate what she is capable of.

Published in eldiario.es , Work / Employment , Work and employment

About Luis Molina Temboury

Economist specializing in statistical analysis of inequality. Convinced that to reverse the escalation of extreme inequality we will have to agree on a limit to wealth. The sooner the better. Member of Economists Against the Crisis.

Evaluando la gestión de Yolanda Díaz | Economistas Frente a la Crisis

En su libro Un pueblo traicionado, el historiador Paul Preston explica, con profusión de episodios, que durante el último siglo y medio las élites españolas han sido un obstáculo para el progreso por su corrupción e ineptitud. Y que esa desgraciada actitud ha provocado graves problemas sociales...

economistasfrentealacrisis.com

economistasfrentealacrisis.com

Last edited: