-

ICMag with help from Phlizon, Landrace Warden and The Vault is running a NEW contest for Christmas! You can check it here. Prizes are: full spectrum led light, seeds & forum premium access. Come join in!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

commies

- Thread starter Cannavore

- Start date

Americans seem to have an obsession to limiting things to pairs...

There's only room for two parties and two genders and two economic systems.

I hope someone else starts running things soon.

There's only room for two parties and two genders and two economic systems.

I hope someone else starts running things soon.

Eltitoguay

Well-known member

A Black Panther in Franco's Madrid

By Jordi Chantres

BLACK PANTHER PARTY WOMEN ACTIVISTS (1969).

In 1967, Roberta Alexander, a Black Panther activist, held a rally at the University of Madrid against the Vietnam War. The event ended with protests, communist flags and riots in the streets of the city centre. After singing "We shall overcome" in the basement of the DGS (Dirección General de Segurida) she was expelled from the country.

It is an unusual chapter of Francoist dissidence in the heart of Francoism: a black militant of the then newly formed Black Panthers who gave a rally at a Madrid university and, for several weeks, kept Francoism in check .

Her testimony tells us about the famous "jumps" (meetings with the intention of demonstrating that lasted minutes until the armed police arrived and dispersed them with blood and fire), but also about the impetus of the radicalized students, who did not hesitate to take over the campus and demonstrate in front of the United States institutions in Madrid to protest against the Vietnam War, which had become the great internationalist cause of the second half of the sixties.

FROM BERKELEY'S PACIFISM TO THE MADRID OF THE GRAYS:

BLACK PANTHER ACTIVIST AT A PROPAGANDA TABLE (1969). PHOTOGRAPH: DAVID FENTON

Roberta was not a newcomer to activism. Before joining the Panthers, she had participated in the Free Speech Movement , the civil rights movement that emerged in Berkeley.

However, her visit to Spain in the midst of the dictatorship was an experience that had an impact on her.

She knew nothing about our country. She was fascinated by the Civil War and the role of the International Brigades (her uncle had belonged to the Lincoln Brigade, made up entirely of blacks), but little else.

ROBERTA ALEXANDER DURING AN EVENT IN GERMANY. PHOTO: REBELIÓN

She did not travel alone. She was accompanied by two friends, all of them communists . After a long journey by boat (she left New York and, after stopping in Dover, arrived in Le Havre, France, from where she took a train and landed in Madrid), she arrived as an exchange student at the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, which gave her a certain protection . After all, she was a foreign national from a country like the United States, with which, from 1960, Franco's regime, aware of the need to seek economic openness, signed a trade agreement. Franco was trying to "normalize" his international relations. Among other things, the pact meant the publication of numerous American writers through the United States Information Service of the Embassy (John Dos Passos, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Erskine Cladwell, John Steinbeck, James T. Farrell, Pearl S. Buck or John P. Marquand, among others).

As soon as she arrived, she was greeted by Carlos Blanco, a Marxist, writer, literary critic and director of the exchange program. Roberta did not know that he would be instrumental in the events that were to come.

The first few weeks were strange. She was determined to get involved in political activism despite the repression, but she was unable to find any leftist groups. “At first I couldn’t find the political people, because the students would throw out leaflets and disappear, there would be a demonstration and they would disappear, I couldn’t find out who was behind it, or meet anyone,” she told Luis Martín-Cabrera in an interview published in Rebelión in October 2011. Carlos Blanco secretly organized the students, who were planning a boycott of Ronald Reagan’s visit to Madrid. They would go to the airport to greet him with banners, but the trip was eventually cancelled . Without hesitation, some mornings she set up several information tables at the entrance to the faculty denouncing the war. It was then that, in order to put pressure on the Spanish government not to renew its agreements with the United States on the use of its military bases in Spain, especially in Torrejón de Ardoz, a campaign against the Vietnam War and imperialism was organized that would begin on April 28.

THE BLACK PANTHER WHO SPOKE TO THE STUDENTS OF MADRID:

"You have to get out from behind those bushes, we have a taxi waiting for you; the best thing is that you go to Andalusia for a couple of weeks until they forget about you."

Roberta, although with reservations, agreed to speak at a rally at the university. The idea was to speak only about the United States, but not to make any reference to Franco. Outside, some groups were burning American flags , while the hall was packed (between 400 and 500 people). Everyone was looking towards the door, waiting to see the police enter. Roberta spoke excitedly. The audience, which had a real panther in front of it, burst into a great ovation.At the end, what seemed almost inevitable arrived :

«I was already getting ready to leave when a small group of students, led by Fini Rubio, came up to me and said: “You have to go behind those bushes, we have a taxi waiting for you; the best thing is to go to Andalusia for a couple of weeks until they forget about you .” This didn’t seem like a very promising plan [laughs]. I hadn’t thought much further, it hadn’t occurred to me what would happen after the speech, until these students told me that they had a taxi waiting for me. In this sense, I was quite naive. I knew that the Andalusia plan wasn’t going to work, so I went to my small apartment and then I spoke to my friend, Karen Winn, who was still living in a boarding house. Karen was blonde and Carol Watanabe was of Japanese origin. They had both helped me set up the tables for the petition, but they hadn’t made any speeches. The woman at Karen’s pension told us that the police had come to get us and that she had told them that we would be back in four hours so that we would have time to escape. We packed quickly and called Carlos Blanco and asked him, “What do we do now?” “Come to my house immediately ,” he said. We grabbed a taxi just at siesta time and suddenly on the radio there was something about “the colored girl, the blonde and the Japanese girl from Berkeley who have insulted Spanish hospitality.” The taxi driver must have been a legit guy because he looked in the rearview mirror and realized who his clients were. He dropped us off at Carlos Blanco’s house where we spent 2 or 3 days. At the Blancos’ house it became clear that they were not going to just forget about us so we decided to go back to our respective places of lodging. I returned to my apartment and was there eating a yogurt when two men in plain clothes knocked on the door and said, “Are you Roberta Alexander?” which was little more than a joke. I said yes and they told me that I was under arrest . I asked why and they told me: “We don't know why, the American Embassy sent him to us.”

UNREST IN THE CENTER: THE BLACK FIST FLYING OVER THE CAPITAL:

Roberta was under arrest, the first and last time a Black Panther was arrested in Franco's Spain .

However, while she was being taken to police stations in various parts of Madrid, more things were happening.

The Diario de Burgos , in its April 29 edition, recounts what happened:

"Student demonstration in Madrid “against the US policy in Vietnam” :

"It seems that it was young Americans who took the initiative for the organization.

Madrid (Cifra).

— Several hundred students met this morning at the Faculty of Political and Economic Sciences to demonstrate against American policy in Vietnam. In the classroom where the meeting took place, North Vietnamese flags, portraits of President Johnson and slogans against the policy and action of the United States in South-West Asia were displayed. Clippings from foreign newspapers about "bombing of civilian populations" were read, as well as statements by Ho-Chi-Minh, the Englishman Bertrand Russell and a group of so-called Spanish Intellectuals who were taking part in the demonstration.

A black American student from the University of Berkeley, Roberta Alexander, who is in Spain on a university exchange, spoke out against American intervention in Vietnam and referred to racial discrimination in the United States. Among those attending the meeting there was a large number of American students who are studying in Spain under agreements established for student exchanges. It is understood that it was from these student groups that the directive for the preparation and organisation of these demonstrations against the policy of their own country in Vietnam arose, seeking the collaboration of some Spanish students. The student Roberta Alexander had recently published a letter in the New York Herald Tribune in which she tried to justify the disturbances in Madrid. Confirming the letter were other American students Carol Batanave and Karen Win. The latter comes from the Californian University of Berkeley and has declared to a foreign agency in Madrid: " We will not participate in the demonstration because if the blond hair stands out too much" , although she admitted that American students had participated in the organisation of this demonstration against the United States, for its policy in Vietnam."

ROBERTA ALEXANDER ON THE LEFT OF THE IMAGE WITH HER FIST RAISED

« A hundred students burned American flags that had painted on them and some drawn portraits of President Johnson»

"At the end of this meeting, around a hundred students, led by others carrying banners against President Johnson and the United States policy, went to the esplanade of the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, where they burned some American flags painted on them and some drawn portraits of President Johnson . The smoke produced by the bonfire approached the group of public forces on normal law enforcement duty, at which point the students dispersed without any need for a request or intervention by the authorities. In the afternoon, around eight o'clock, a few hundred students, divided into small groups, positioned themselves around the United States Embassy on Serrano Street in an attempt to demonstrate. The public forces were guarding the political representation and, faced with the attitude of some of the groups of not disbanding while shouting "imperialists", they were forced to charge. The incidents were divided along Calle Serrano and its tributaries, such as the intersection of Calle Serrano and Calle Goya, where a small group set fire to several newspapers. Here, too, the police were forced to intervene, as they did in response to the actions of another group located at the intersection of Calle Serrano and Calle Hermosilla and Calle Claudio Coello and Calle Goya. It is known that, as a result of all these disturbances, the police have made several arrests. The disturbances, on the other hand, affected traffic in the area , which is always very intense and even more so at the time of day when they occurred, which caused several traffic jams. By early evening, normality had been completely restored."

PROTESTS IN THE SPANISH COMMUNIST PRESS IN EXILE. ABOVE, STUDENTS (SOME WITH THEIR FACES COVERED) DEMONSTRATE. BELOW, POLICE CHARGES BREAKING UP THE MARCH ( LPE , MAY 15, 1967)

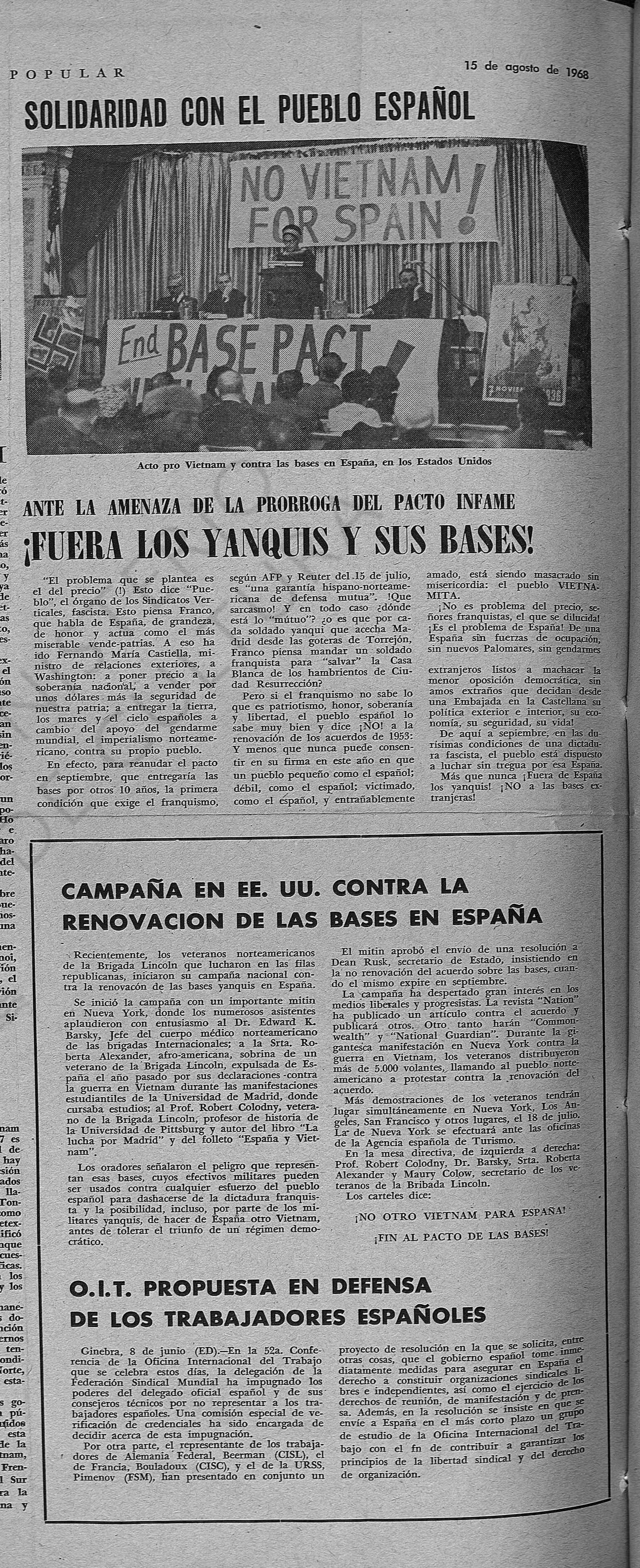

ROBERTA GIVES A SPEECH AT AN EVENT HELD IN THE UNITED STATES, AFTER HER RETURN FROM MADRID, AGAINST THE VIETNAM WAR AND THE AMERICAN BASES IN SPAIN ( ESPAÑA POPULAR , AUGUST 15, 1968)

"WE SHALL OVERCOME" PLAYS AT THE GENERAL SECURITY DIRECTORATE:

Roberta herself continues the story in her interview:

«Although it may seem incredible, we walked from my little apartment in Callao to the Puerta del Sol and in my memory we even stopped for a coffee. Strange, isn’t it? It seems incredible now, but that’s how I remember it and how I’ve told it, walking with the Francoist police to the Puerta del Sol. Anyway, they put me in the General Directorate of Security and it really was like going down to the dungeons of a castle. They put me in a cell by myself and by then I was starting to get a little scared, although Carlos had told us that if they arrested us he would keep an eye on us, it was the only connection he had with the outside world that could protect us at that moment […]

I remember that someone started singing a song that sounded familiar to me from the movement , but as I am from a later American generation, I didn’t recognize it immediately, but I started humming it with him and one of the guards came up to me, really angry: “Why are you singing that song?” And that’s when I realized it was “The Internationale.”

“While I was in detention, I pretended as much as I could that I couldn’t speak Spanish, I would tell them, ‘I don’t know what that is,’ and they would leave. Nothing happened to me, physically or otherwise. Then someone noticed that there was an American woman in the cells.

I didn’t see any other prisoners, but it was full, because they had arrested a lot of people just before May Day, they were preventive arrests.

Then someone started singing ‘We shall overcome’ [the anthem of the Civil Rights Movement led by Martin Luther King], they couldn’t silence us and we were singing in English! I think it was in English.”

Video of a recent lecture by Roberta Alexander on the Black Panthers:

The embassy managed to press for her release. She was placed under house arrest pending her deportation, which took place at the beginning of May. A dozen police officers accompanied her to the train that would take her to Irún. At the station in Madrid, there were apparently some charges against students who came to say goodbye to her and protest against her deportation. At the border in Irún, the agents verified that they had crossed the border. Already in Hendaye, a group of people were waiting for her with some money and the contact information of friends in Paris, who would also help her. In the French capital she gave an interview to CBS and, back home, her case made the front page of the Los Angeles Times .

Some time later, she wrote a letter to the editor of the newspaper Ya , which was published in its section “See it and... tell it .” An American sympathizer of the regime had written a letter accusing her of disloyalty and treason. The response is this:

"Dear Sir:

I am writing this letter in response to the letter published in your newspaper on June 14, which referred to the "misconduct" of myself and the two other girls expelled from Spain. I do not think that the lady who wrote the letter fully understands our position regarding the Vietnam War. I believe that the American people must always express their opinions. We say that we have a democracy, but we must bear in mind that the word democracy has no meaning without the freedom to express different opinions. Those of us who criticize the role of the United States in the war and who protest against the injustices of our society are not "social defects" but true patriots and democrats. I think that the Vietnamese people, like all peoples of the world, have the right to determine their own government without military intervention by the United States. Who receives the advantages and who pays the price of war? The young black man may fight in Vietnam against colored people, but in his own country he lives as an inferior citizen. That is why I protest against the war. I just hope that the people of the world, especially the American people, will take a second look and think a little more about our country's policy in Vietnam.

ROBERTA ALEXANDER

Roberta Alexander telling the story of her deportation

to a group of brigadier of the LIncoln

to a group of brigadier of the LIncoln

ROBERTA, SECOND FROM LEFT, RAISES HER FIST DURING A CONFERENCE ON BLACK POWER.

Una pantera negra en el Madrid franquista — Agente Provocador

En 1967 Roberta Alexander, militante de Panteras Negras, dio un mitin en la universidad madrileña contra la guerra de Vietnam. El acto acabó con cargas, banderas comunistas y disturbios en las calles del centro. Tras cantar «We shall overcome» en los sótanos de la DGS fue expulsada del país

Last edited:

Eltitoguay

Well-known member

Interview with Roberta Alexander, a living history of activism in the US (1 of 4):

By Luis Martín-Cabrera | 04/10/2011 | USASources: Rebellion

Intro:

Often the news we receive from the United States has to do with the multiple war fronts opened by the empire, the religious fanaticism of the evangelical right, junk food, the sexual scandals in public life, its regressive puritanism, the stupidity of its television series, its self-assigned role as global police or its insistence on perpetuating a global capitalist system of exploitation and destruction of the planet. Outside the United States, even large sectors of the left, when they think of the “belly of the monster” as Martí called it, imagine white, upper-middle-class Americans, obese, ignorant of everything that happens outside their country, concerned only with continuing to fill their refrigerators with food and the gas tanks of their trucks, completely oblivious to the bloody origin of the oil that sustains their American way of life .

There is no doubt that this reality exists, but the country is much more heterogeneous than we imagine outside its borders. In addition to the complacent white middle class and the plutocracy in power, there are other realities in the United States, those of those who suffer firsthand the oppressive and exploitative policies of the United States, the voice of those below, the rebellious dignity of those who resist and fight from within to overthrow a fundamentally unjust, structurally racist, compulsively exploitative and irremediably oppressive system. The purpose of this series of interviews is precisely to make known beyond the borders of the United States the political subjectivities of those of us who fight from within, knowing that a better and more just world is impossible without a radical change within the United States.

No one better to inaugurate this series of interviews from the “heart of the beast” than Roberta Alexander. Roberta Alexander is the daughter of a communist couple, the product of an interracial relationship when marriages between whites and African-Americans were prohibited, a militant herself of the Communist Party of the United States, a member of the WE Dubois Club, of the Black Panthers, an activist in the student movement in Berkeley, an English teacher in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods, Director of the English Department in one of the most combative University Schools in the district of San Diego, a living history of militancy in California and in the United States. If it were not too disrespectful I would even say that reading these interviews and, hopefully in the very near future, the memoirs she is writing, is very close to a revolutionary version of the movie Forrest Gump , except that here Roberta Alexander is not just a passive or unconscious witness, but an active participant in a turbulent and hopeful time.

The conversations with Roberta Alexander extend over several sessions and the hours seem like minutes, because they are filled with countless anecdotes and moments that convey the rage and dignity of the shared struggle; other voices speak through her words, the aspirations and hopes of the most humble, the most oppressed hearts that do not appear in the history books, but who have opened more paths than any national hero or industrial titan. Like many of the most dedicated activists, Roberta Alexander does not have the feeling that her life or her activism are particularly important. Readers of these interviews will be able to see to what extent she is wrong in this. Once one begins to pull the thread of the story, her irrepressible loquacity, her irremediable sense of humor in the face of the most adverse circumstances (I have not been able to transcribe all the laughter that punctuated our conversations), and her political courage stay with us forever. I hope that at least a trace of that intensity remains in these interviews:

"We had above all a deep appreciation, respect and affinity for the working class of all colours and ethnic groups."

Continue:Interview with Roberta Alexander, a living history of activism in the US (2 of 4):

"The Spanish guards told us over and over again that they knew nothing about our situation, that they were following orders from the American Embassy."

Continue:Interview with Roberta Alexander, a living history of activism in the US (3 of 4):

«Bobby Seale talked about sharing the pie, but I didn't want a piece of the pie, I wanted to overthrow capitalism»

Continue:Interview with Roberta Alexander, a living history of activism in the US (4 and the end):

«Lubumba-Zapata was the only place that taught history from the perspective of blacks, Chicanos, and working-class whites.»

Continue:

Last edited:

Eltitoguay

Well-known member

In line with your question, I also wonder what would have happened to my family (middle or lower-middle working class) if I had lived in the United States, with the current prostate cancer that my elderly father is going through, and overcoming. Such a complex treatment, with so many drugs and sessions with expensive localized radiotherapy equipment... I wonder how much that would cost in the US... Here it is practically free. And let's not talk about diseases that are even more complex and/or economically expensive to treat...So to the euros out there who are reading this -- gaius, gypsy, montuno, etc -- is the NHS and other taxpayer health insurance programs/free health care considered communism where you are from?

how do the right wing/conservative parties feel about this type of health care plan?

should a person go bankrupt from medical bills? is this morally acceptable to allow people to go into debt from bills or to die because they put off seeing a doctor? becuase these are huge problems in the US. we are not a healthy country as a whole.

is asking for what the rest of the developed world has = communism? becuase in a nutshell arguement this is basically the furthest "left" policy being discussed in the US, with Joe Biden not even willing to entertain the idea that this is possible (even though it is, he's just a absolute shill for medical corporations and big business).

Of course, in the area of Dentistry, and in Psychology & Psychiatry (not related with drugs addictions problems) the service is very basic, and for complicated things, you end up resorting to Private Healthcare.

In the case of my country, it has been an achievement of the left's struggle that has been built since 1908. The right does not dare publicly to be against it and demagogically claims in public that it wants to maintain the model, but tries to boycott it when it governs, allocating more and more of the public money for universal and free public healthcare, to promoting and financing private healthcare (in the one that usually has economic interest) and the "concerted" one (public means, private means of payment).

In fact, during the previous Government of Mariano Rajoy and the Popular Party, they dismantled everything they could from Public Health, and there were shady deals with Private Health.

Here is a Wikipedia summary of the history and how the Public Health System works:

The National Health System is the body that encompasses the health benefits and services in Spain that, according to law, are the responsibility of the public authorities. Created in 1908, it gradually extended its coverage, subject to payment for the healthcare services, to the entire Spanish population. In 1989 this process was completed; since then, healthcare in Spain has been universal and supported through different types of taxes.

In Spain, in accordance with the principle of decentralization promulgated by the Constitution and after the dissolution of INSALUD in 2002, health care competence is transferred to each of the Autonomous Communities . The central government only provides this service directly in Ceuta and Melilla (the two smallest Autonomous Communietes, on the northwestern Mediterranean coast of Africa), through the National Institute of Health Management (INGESA) and carries out general and basic tasks between the different Communities.

History and regulatory framework

Public intervention in community health problems was always a matter of interest, expressed fundamentally in the control of epidemics , or at least in the minimum capacity of control allowed by naval quarantines , the closing of the walls [ 2 ] and the prohibition of communications [ 3 ] with cities affected by the plague , and other types of measures that were supposed to be hygienic or palliative.) After the flourishing of medicine in al-Andalus and the outstanding contribution of the Jews during the Late Middle Ages , the institutionalization of the protomedicato took place in the time of Charles I. But the practice of the medical profession, which was accessed through the faculties of medicine from the medieval university, was highly decentralized and had organizations such as medical colleges . Surgery and pharmacy were disciplines well differentiated from medicine, and much less prestigious, within the Galenic-Hippocratic paradigm dominant during most of the Ancien Régime in Spain .The novatores of the late 17th century had medicine as one of their main fields of action, which was limited to individual and localized initiatives, which the Spanish Enlightenment of the second half of the 18th century developed with more continuity ( College of Surgery of San Carlos , etc.) At the beginning of the 19th century , the Royal Philanthropic Vaccine Expedition (1803) constituted the most ambitious public health project on a planetary level.

Already in the Contemporary Age , during the liberal triennium , they discussed the Health Code of 1822 , which was not approved due to the lack of scientific and technical consensus on the means that should be provided. Already in the period called progressive biennium , the Law of November 28, 1855 [ 4 ] consecrates the General Directorate of Health , created very few years before, and which will have a long organizational continuity. The Royal Decree of January 12, 1904 , which approves the General Instruction of Health, barely altered the organizational scheme of 1855 (changing the name of the General Directorate of Health for the General Inspection of Health from time to time).

On July 11, 1934, during the Second Spanish Republic the Law of Health Coordination was enacted, with the fundamental objective of accentuating the incipient state intervention in the organization of local health services; it proposes the creation of the Ministry of Health. [ 5 ]

After the Spanish Civil War , with the Franco dictatorship, the 1944 Law of Bases perpetuated the previous structure: [ 6 ]

The Law of December 14, in 1942 created the Compulsory Sickness Insurance SOE , under the management of the National Institute of Social Security , a system of coverage of health risks through a quota linked to work, restructured in the General Law of Social Security of 1974. [ 7 ] Social Security was assuming an increasing number of pathologies within its benefits table, as well as covering a greater number of people and groups. However, a WHO report in 1967 detected important deficiencies in the system [ 8 ]The Public Administration is responsible for addressing health problems that may affect the community as a whole; in short, it is responsible for developing preventive action. The assistance function, the problem of addressing individual health problems, is left aside.

With the democracy, the General Health Law (April 25, 1986) [ 9 ] and the creation of Health Departments and a Ministry of Health , are a response to the provisions on public health of the Spanish Constitution of 1978 in articles 43 and 49 establishes the right of all citizens to health protection and title VIII, which provides for the powers in matters of health of the autonomous communities .

General Health Law 14/1986

The General Health Law was formulated for two reasons, the first of which is that it originates from a mandate of the Spanish Constitution, since both Article 43 and Article 49 of the fundamental normative text establish the right of all citizens to health protection. The Law recognizes the right to obtain health system benefits for all citizens and foreigners residing in Spain.The second reason is of an organisational nature, since Title VIII of the Constitution confers broad powers on the autonomous communities in the area of health. The autonomous communities have a primary importance in the organisation of health care and the Law allows the implementation of the processes of transfer of services, a health care system sufficient to meet the health needs of the population resident in their respective jurisdictions. Article 149.1.16 of the Constitution, on which this Law is based, establishes the principles and substantive criteria that allow the new health care system to be given general and common characteristics that are the foundation of health services throughout the territory of the State.

The administrative tool proposed by the Law is the configuration (it does not create it, it only configures it), [ 10 ] of a National Health System . The axis of the model that the law adopts is that the autonomous communities are sufficiently endowed and with the necessary territorial perspective, so that the benefits of autonomy are not compromised by the needs of efficiency in management.

Health services are therefore concentrated under the responsibility of the autonomous communities and under the powers of direction, in the basic sense, and the coordination of the State. The creation of the respective health services of the autonomous communities has been carried out gradually as the transfers in the area of Health were carried out.The National Health System is thus conceived as the set of health services of the Autonomous Communities conveniently coordinated.

The Health Law was supplemented in 2003 by Law 16/2003 on cohesion and quality of the National Health System , [ 11 ] which, while maintaining the basic lines of the Law, modified and expanded the article to adapt it to the new social and political reality in force in Spain.

General Law on Social Security

Royal Legislative Decree 1/1994, of June 20, approving the revised text of the General Law on Social Security, in its Chapter IV deals with protective action . This includes:- Health care in cases of maternity , illness (common or occupational) and accidents , whether or not they are work-related.

- Professional recovery , the provenance of which is appreciated in any of the mentioned cases

- Economic benefits in situations of temporary disability ; maternity; paternity ; risk during pregnancy ; risk during breastfeeding ; care of minors affected by cancer or another serious illness ; disability , in its contributory and non-contributory modalities; retirement , in its contributory and non-contributory modalities ; unemployment, in its contributory and assistance levels ; death and survival ; as well as those granted in the contingencies and special situations that are determined by regulation.

Law 16/2003 on cohesion and quality of the National Health System

This Law was promoted in 2003 when all the autonomous communities gradually assumed responsibilities in the area of health and a stable model of financing of all the assumed responsibilities was established.Several years have passed since the General Health Law came into force, and profound changes have taken place in society, both culturally, technologically and socio-economically, as well as in the way of living and becoming ill. And new challenges have arisen for the organisation of the National Health System.

For all these reasons, this law establishes actions for coordination and cooperation between public health administrations as a means of ensuring citizens' right to health protection, with the common objective of guaranteeing equity, quality and social participation in the National Health System.

The Law defines a common core of action for the National Health System and the health services that comprise it. Without interfering in the diversity of organizational, management and service delivery formulas inherent to a decentralized State, it is intended that citizen care by public health services respond to basic and common guarantees.

The areas of collaboration between public health administrations defined by this law are: the services of the National Health System; pharmacy; health professionals; research; the health information system; and the quality of the health system.

In this way, the law creates or strengthens specialized bodies, which are open to the participation of the autonomous communities; such as the Technology Assessment Agency, the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products , the Human Resources Commission, the Health Research Advisory Commission, the Carlos III Health Institute , the Health Information Institute, the National Health System Quality Agency [ 12 ] and the National Health System Observatory.

The basic organ of cohesion is the Interterritorial Council of the National Health System of Spain , which is provided with greater agility in decision-making and mechanisms for seeking consensus, as well as for the link between the parties in the assumption of these decisions. The system includes the High Inspection, which is assigned the monitoring of the agreements of that one, among other functions. [ 13 ]

Spanish health coverage:

The beneficiaries of the public health benefit are all Spaniards in accordance with the provisions of Chapter III of the Spanish Constitution approved in 1978. Specifically, it establishes that: [ 18 ]- Article 41: The public authorities shall maintain a public social security system for all citizens, guaranteeing adequate social assistance and benefits in situations of need, especially in the case of unemployment. Assistance and complementary benefits shall be free.

- Article 43: The right to health protection is recognized. It is the responsibility of the public authorities to organize and protect public health through preventive measures and the necessary benefits and services. The Law shall establish the rights and duties of all in this regard. The public authorities shall promote health education, physical education and sport.

- Article 49. The public authorities shall implement a policy of prevention, treatment, rehabilitation and integration of the physically, sensorially and mentally handicapped.

- Article 3. Foreigners shall enjoy in Spain, on equal terms with Spaniards, the rights and freedoms recognized in Title I of the Constitution and in its implementing laws, in the terms established in this Organic Law.

- Article 10. Foreigners shall have the right to engage in paid activity on their own or as an employee, as well as to access the Social Security System, under the terms provided for in this Organic Law and in the provisions that develop it.

- Article 12. Foreigners who are in Spain and registered in the municipal register of their habitual residence have the right to health care under the same conditions as Spaniards. Foreigners who are in Spain have the right to emergency public health care in the event of serious illness or accident, whatever the cause, and to the continuity of such care until they are discharged from the hospital. Foreigners under eighteen years of age who are in Spain have the right to health care under the same conditions as Spaniards. Pregnant foreign women who are in Spain have the right to health care during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period.

Financing of Public Health

Article 10 of the Law on cohesion and quality of the National Health System establishes that the financing of Public Health in Spain is the responsibility of the autonomous communities in accordance with the transfer agreements and the current system of autonomous financing, without prejudice to the existence of a third party obliged to pay. The sufficiency for the financing of the benefits is determined by the resources assigned to the autonomous communities in accordance with the provisions of the autonomous financing laws. The financing of health care derived from professional contingencies is through premiums for work accidents and occupational diseases. It is provided by the public health service at the expense of the managing entity (INSS or ISM) or the mutual or collaborating company (in this case directly) with whom the company or the worker, in the case of self-employed workers who opt for coverage of professional risks, have agreed to cover professional contingencies. The inclusion of a new benefit in the catalogue of benefits of the National Health System will be accompanied by an economic report containing the assessment of the positive or negative impact that it may entail. This report will be submitted to the Fiscal and Financial Policy Council for analysis and approval, if appropriate.Privatization of health care

With the approval in 1997 of Law 15/1997 on new forms of management of health centres, the door was opened in Spain to the construction of new privately managed public hospitals paid for with public funds and to the privatisation of the management of health care or non-health care services, depending on each case. Thus, in 1999, the Alcira Hospital was the first public hospital in Spain in which its management was privatised, and therefore, its health care staff . Likewise, various communities governed by the Popular Party carried out initiatives to build privately managed public hospitals under the legal formula of health foundations, of which the Calahorra Hospital (La Rioja) is an example .On November 1, 2012, Ignacio González , President of the Community of Madrid , announced during the presentation of the 2013 Budget Project the privatization of the management of six hospitals in the community and 10% of the primary care centers in the region, including the health personnel . This measure has mainly affected the Hospital de La Princesa , where various demonstrations have taken place. [ 44 ] [ 45 ] [ 46 ]

In Spain, private healthcare is defended by certain pressure groups and lobbies, representatives of insurance companies and hospital groups. Among them is the Idis Foundation, directed by Juan Abarca Cidón , [ 47 ] which was very present during the Covid-19 pandemic to obtain various contracts with the regional health system. [ 48 ]

Suspension of the trial in Madrid

On 27 January 2014, the then President of the Community of Madrid , Ignacio González , announced that the project to privatise the management of six public hospitals was being suspended , following the decision of the High Court of Justice of the Community of Madrid to halt the process. He then said that he had accepted the resignation of the Minister of Health Javier Fernández-Lasquetty , the main person responsible for the project - which had encountered strong opposition among healthcare personnel and users of Madrid's public health system in the so-called white tide -. [ 49 ] However, the hospitals previously created with this type of formula did not revert to pure public management. It should be noted that the reversion of privatised services to public management presents major legal problems, particularly in the management of personnel, as the Valencian Government found out when it recovered management of the Alcira Hospital .More:

Last edited:

Eltitoguay

Well-known member

Yes, it's good, yes, je, je...man you're doing the meme LOL!

Last edited:

Eltitoguay

Well-known member

(...)"In principle principle, the Spanish section of the Black Panther Party was not created to take revenge on the Nazis , but because Spain was diluting blacks in the Hispanic world, denying them"(...)The Black Panthers in Spain: how the revolutionary vanguard that fought Nazi and racist attacks was formed

By Henrique Marino.

Madrid; 04/25/2024

Beatings, racism and political awareness led several young of Equatorial Guineans origins, to create "a secret self-defense strategy" against the rise of the far right in the 1990s.

Members of the Black Panthers of Zaragoza, in 1992. — Black Panthers Archive

In the early 1990s, nazi skinheads were rampant in Madrid and other cities. Fed up with racist attacks and insults, the young people of the black movement decided to organize and develop a "collective strategy based on self-defense against the impunity of Nazi terrorism." This is how the Black Panthers were born in Spain, although the embryo had been conceived years before in the context of student protests — whose punk icon was Cojo Manteca —, the rise of hip hop and the fury of street gangs.

However, they needed an organisation that would unite its members and leaders who would instil in them an ideology and a conscience to undertake the racial struggle. Abuy Nfubea , a young man of Equatorial Guinean origin, was one of those responsible for recruiting and training subversive, committed and combative elements to provide cadres for the Black Panthers, recognised in 1994 as the Spanish section of the American New Black Panther Party.

View attachment 19057433

New Black Panther Party - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

Nuevo Partido Pantera Negra - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

es.wikipedia.org

He knew the theory, but it was time to put it into practice. He and other comrades had been immersed in the doctrine of Malcolm X and had read Kwame Ture's book Black Power , although they were aware that the cause was fragmented and needed the glue of what would later become the Black Panthers, whose first state congress was held in 1992. The setting was Alcalá de Henares, which housed two institutions that were decisive for the development of the movement: the campus of the Universidad Laboral and the Pedro Gumiel Institute.

"Malcolm X was inspired by rap and by the Torrejón de Ardoz air base, where we went to the Stone's nightclub , which was frequented by Americans. In addition to his autobiography, we read the magazines Mundo Negro , Tam-Tam and África Negra ," explains Abuy Nfubea, who set out to spread his thesis beyond academic circles and onto the streets. Not only to gangs, but also to other types of brotherhoods, as there was a seed of protest among grassroots Christians and other groups.

On campus, he says, a confrontation arose between two factions: "The black Uncle Toms , kneeling and colonised, who were around the Colegio Mayor Nuestra Señora de África [attached to the Complutense University of Madrid]; and other more radical, politically aware and from a lower social class, who were around the Universidad Laboral de Alcalá and Father Asier." Although Abuy Nfubea was a middle-class lad educated by the Jesuits, he converted to the working-class and pan-Africanist cause.

While some classified his people as immigrants or, at best, as black citizens, he advocated the concept of a black community. The different perspectives when it came to tackling the social struggle against racism came from a long time ago and, in today's eyes, can seem shocking and contradictory. There were organizations linked to Catholics and evangelicals - and even related to Opus Dei - as well as militants from right-wing and left-wing parties, both Spanish and Equatorial Guinean.

In fact, the fathers of several members of the Black Panthers were Francoists and some were military men, such as the grandfather of Enrique Okenve Martínez or the father of Javier Siale Bonaba, an anti-fascist ska fan who was a member of the Sharps (Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice).

View attachment 19057457

View attachment 19057458

Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

For his part, Abuy Nfubea is the grandson of a procurator of the Francoist courts and the son of the founder of Unión Popular, a conservative party that inherited various pro-independence political parties in Equatorial Guinea.

With a background in opposition to dictators Macías and Obiang, as well as the Free Mandela movement , those boys knew or lived through some founding milestones that preceded the creation of the Black Panthers, such as the sexual assault of two Guinean women in Móstoles during the 1982 World Cup in Spain, the reaction to which was the birth of the Black Panthers Feminist Collective; or the campaign against the withdrawal of the black man from Banyoles and the subsequent defence of his liberator, the Haitian Alphonce Arcelín.

The attack on the South African embassy to denounce apartheid in 1986 was also notorious, which later motivated the creation of the solidarity committee with Marcelino Bondjale, leader of Maleva . An action that referred to the seizure of the Guinean diplomatic legation ten years earlier, in protest against the Macías regime. The struggle of many parents - some linked to Falange or Fuerza Nueva - for independence and against the dictatorship, first in their country and then in exile, had become outdated. When their children took over and went into action, the enemies were at home: the neo-Nazis, sometimes integrated or protected by members of the state security forces. In fact, the murderer of Lucrecia Pérez in 1992 was a civil guard.

To confront them, they recruited members of the most powerful gangs and brotherhoods: Radical Black Power, Simplemente Hermanos, the Colours, MAN, West Side, the BRA - founded by Fermín Nvo, known as T-7 and considered by the Black Panthers to be the godfather of hip hop -, the Black Stones, Public Enemy Fan Club, Boricua, FTP and the Madrid Vandals , who were joined by some anti-racist skinheads. "We had to organise ourselves militarily so that they wouldn't smash our heads in," explains Abuy Nfubea, who recalls the neo-Nazi attack suffered in a restaurant in Móstoles by Africans celebrating Cameroon's victory over Argentina in the 1990 World Cup in Italy.

"In principle principle, the Spanish section of the Black Panther Party was not created to take revenge on the Nazis , but because Spain was diluting blacks in the Hispanic world, denying them," clarifies the journalist and writer.

However, in 1995, on the occasion of the second state congress, the newspaper El Mundo headlined: The Black Panthers organize to fight against the Nazi skinhead phenomenon .

Violence from the extreme right was a constant at the beginning of the decade, as reflected in another news item published in 1993: Two nazi skinheads end up stabbed after starting a fight against three blacks .

Four neo-Nazis had boarded a commuter train heading from Atocha to Fuenlabrada and shouted: "We are going to kill the blacks." The injured denied it, but El País made it clear that the police version confirmed the initial insults uttered by the skinheads , one of them a soldier.

Events like this had motivated, three years earlier, the Black Panther movement to advocate "the creation of an immediate secret strategy of self-defense against Nazi skinhead terrorism," while some neighborhoods of Alcalá de Henares had graffiti on their walls: "Black Panthers: by any means necessary."

"Young people were attacked by the bouncers at the discotheques and by the Nazis, who intimidated the boys and girls. Then, after the incident on the commuter train, black people began to patrol the trains and confront them," recalls Abuy Nfubea. And, conversely, was there a hunt for Nazis? "Of course, there was a context of confrontation. That was the situation," admits the founder of the Organised Front of African Youth ( FOJA ). "However, racist violence went unpunished, while activists suffered not only reprisals from the State, but also from Free Mandela, who called Marcelino Bondjale violent, expelled him and caused the movement to break up."

"We had a national vocation and we wanted to extend the Black Panther Party throughout the State. There were already people fighting in other places, but we provided them with an organic, political, ideological and philosophical base," says the author of the book Afrofeminism: 50 years of struggle and activism of black women in Spain (Ménades). Thus, they managed to expand from Madrid - and cities such as Móstoles, Torrejón, Fuenlabrada or Alcalá - to Barcelona, Valencia, Barcelona, Zaragoza and Bilbao, although they also reached towns such as Bembibre (El Bierzo) or Burela (Lugo), where the Cape Verdean community worked in the mines and in fishing.

Abuy Nfubea believes that the main legacy of the Black Panthers was the creation of the black community in Spain:

"It was a disciplined organisation whose objective was not only Nazi retaliation, but also political training and teaching about our history. We wanted to bring black people together, because Adolfo Suárez had carried out affirmative action policies, such as the decree on granting Spanish nationality to certain Guineans.

However, after the law on reparation and recognition of the black people, approved by a right-wing government, the PSOE created an equalising model," says the journalist and writer.

"That is to say, for the left, everyone is equal, there are no blacks or whites. But we were aware that this process was leading us to annihilation, so we were clear that we had to create a movement to defend our community," concludes Abuy Nfubea, who at the beginning of the century decided to re-establish the Black Panther Party, together with dozens of organisations in the Spanish State, in the Pan-Africanist movement. Its members were already too old to continue fighting in the streets, but they will continue to be present in the pages of a book he has written about the revolutionary vanguard of black youth.

Los Panteras Negras en España: así se gestó la vanguardia revolucionaria que combatió las agresiones nazis y racistas

Las palizas, el racismo y la conciencia política llevaron a varios jóvenes ecuatoguineanos a crear "una estrategia secreta de autodefensa" ante el auge de la ultraderecha en los noventa.www.publico.es

@Cannabrainer , when I reread this paragraph said by Abuy Nfubea,...

Abuy Nfubea - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

Abuy Nfubea - Wikipedia

(...)"Latino and Hispanic are broad concepts - very broad and therefore lacking identifying value - that dangerously erase cultural heterogeneity on both continents at an international level, but also intra-national diversity." (...)

(...)"I claim the power of not allowing oneself to be named or defined by dominant groups that, to tell the truth, have neither the interest nor the capacity to understand the complexity of the processes of identity construction in multiethnic and multiracial countries, especially since the advent of the paradigms decolonial. There is an aspect in your gaze that does not observe that interest. In mine there is a more sociological and political one that highlights what Barth (Ethnic Groups and Boundaries) called the dynamics of inclusion and exclusion of ethnic groups that clashes head-on with the idea of meta-ethnicity as this dynamic can be understood by those that do not assume our multiplicity. This detail has no specific relationship with what you have raised, since by saying that "cultural identities add up, overlap, or intersect" there seems to be a clear understanding of the complexity of identity multiplicity. However, my approach would be to establish when they do not add up, do not overlap, or intersect, or when, despite this, there is a will of a group to establish dynamics of exclusion and inclusion on its own terms. Obviously, this does not sit well when a metropolis wants to build a common identity for political and economic interests."(...)

Simplifying to the maximum: The "Where the Sun Never Sets"...:

...versus "The 3 Races, and the Equality in the Law" :

...On the other hand, a certain sector of Communism on the "left" of the Communist Party of Spain (very Stalinist and Hoxhaist, in general, such as the Marxist-Leninist Party (Communist Reconstruction)), harshly criticize the current debates/agendas on racial issues. (as they also do with feminism or the diversity of sexual orientations/identities), assuming that these debates and problems do not exist in their ideology and would disappear instantly ("magically", perhaps Abuy Nfubea, would add?) with their policies, accusing capitalism and "revisionist left" to introduce these debates to pervert, dilute and separate the workers' struggle...

I see part of the reason in both positions...although I see that of the P.M.-L.(R.C.) as dangerously close to that of the ultra-right of VOX...

(I looked to illustrate the "imperial posture of where the Sun never sets" a imagen of "a black man from VOX" dressed as Don Pelayo or El Cid Campeador planting the white imperial flag with the red flaming cross in the middle of a camp of "non-Hispanic African" agrarian laborers ", those who pick strawberries, avocados or mangoes..but I couldn't find any, heh...; It would be funny):

versus :

...thank goodness we will always have black humor...or should we eradicate it?"

...Anyway, adopting a mixed style between Michel Ende and Augusto Monterroso: that is a debate that, without a doubt, perhaps deserves to be better debated in another better time...or maybe not...

...Have I already told you, cousin, the joke about the black man, the gypsy man and the cripple/disabled white "payo" man, who are having a party, with a white "merchero" man as the DJ,, while they try to "raised Spain"?...

Anyway...¡Salud, compañero!

Last edited:

Eltitoguay

Well-known member

For all those on the right who still continue with the false mantra "Capitalism vs Marxism = Democracy vs Dictatorship", a brief approach to a nation that has become a "wet dream" of international capitalism like Equatorial Guinea, the so-called "North Korea of the capitalist world":

es.wikipedia.org

es.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

EQUATORIAL GUINEA

17 NOV 2018

Teodoro Obiang

GLOSSARY:

Francisco Macías Nguema —also known as Masié Nguema Biyogo— was the first president of independent Equatorial Guinea, a position he held between 1968 and 1979, the year in which he was overthrown by his nephew Teodoro Obiang. Despite having participated in the previous administration, Macías claimed to be a nationalist. He also said he admired Hitler and, while he lso sought certain ideological harmony within the context marked by the Cold War, and in a purely effectual gesture, his Single National Party (PUN) added an opportunistic T, for "workers", with which Macías, ignorant of the rudiments of the Marxism, tried to establish ties with Cuba and the USSR.

After being ousted from power, he was executed on 29 September 1979.

Public praise was instituted, poverty became suffocating, hospitals became death throes, the Public Administration ceased to exist and a great cloak of darkness covered everything, a silent chaos that was broken by the screams of those tortured in Blay Beach, that prison that became famous. These were the years, shortly after independence, when those convicted for having been declared subversives were subjected to the torture known as Ethiopian torture . This was suffered by those who had not managed to leave the country or those who had not died before from some painful story.

GLOSSARY:

The 'Ethiopian' torture consisted of tying two sticks to the victim's calf and squeezing the ends. It was one of a wide range of practices that included machetes, electric shocks or blows with red-hot iron bars. Political prisoners were sometimes forced to dance while being beaten. Before overthrowing his uncle, Teodoro Obiang Nguema held various positions during his regime, including that of warden of Blay Beach. The dictator, who will celebrate 40 years at the head of the country next year, has based his continuity on oil reserves, obtaining the complicity of foreign powers despite the embezzlement of fortunes and the perennial poverty of the population.

These were the years when rivers of sewage ran through the streets of the cities, when electricity was merely symbolic, when homes were a refuge for vermin. But the worst was the murderous fury of the owners of that power. Those abominable sanitary conditions gave rise to such a high mortality rate that one would say that Guinean lives were cut short by the jaws of death. Public health barely existed even to alleviate that disaster. That infamous life lasted eleven long years and, frankly, Guinea was on the verge of disappearing, despite the fact that there was no power or external force that threatened it, and despite the attention that Macías received from the countries of the communist bloc.

Fraga and Obiang

The former lieutenant colonel made timid efforts to maintain, at least formally, the separation of powers. But in a regime built around the satisfaction of the highest authority, the judiciary, the legislature and his own, the executive, rest shamelessly in the hands of the same person, who is, today, the longest-serving president in all of Africa.

GLOSSARY:

Before overthrowing his uncle, Teodoro Obiang Nguema held various posts during his regime, including that of warden of Blay Beach. The dictator, who will celebrate 40 years at the head of the country next year, has based his continuity on oil reserves, obtaining the complicity of foreign powers despite the embezzlement of fortunes and the perennial poverty of the population.

Almost five years after taking power, Obiang had already taken steps to keep him on a leash, and when the second term was approaching, the clamor about the need for a change in power was already international and general. What happened was that this political necessity was called “multipartyism” and democratic elections. Obiang had a hard time understanding this necessity, and he resorted to what he knew best to demonstrate his intransigence: murder, which resulted in the loss of a few more lives. The case of an alleged coup plotter who sought refuge in the Spanish embassy and was later handed over and imprisoned was notorious.

Civil Guard in Guinea

International pressure and public hopes might have borne some fruit, given that Obiang survived on international aid, but the discovery of oil and gas at the end of the 1990s dashed all hope, while revealing the hypocritical nature of the world powers, many of which were also colonial. Regarding the immense oil reserve, it must be said that there is an idea that has never been openly expressed that either Spain did not know how to discover it or did not want to reveal that it had discovered it. It was the Spaniard company CEPSA that was the first to carry out prospecting on that dormant wealth and that holds the secrets of those discoveries. Strengthened by the monetary power of oil, the Obiang regime almost made the frauds official with the aim of perpetuating itself in power, carried out cosmetic reforms to avoid pressure, but nothing has changed, because power has not changed hands.

GLOSSARY:

Equatorial Guinea is the sixth largest oil producer in Africa, with a production of 281,000 barrels per day in 2014, according to data from British Petroleum. It is also the country that depends most on this resource. But reserves are limited and the drop in the price of a barrel in recent years has resulted in an increase in poverty.

GLOSSARY:

In Equatorial Guinea, billions of euros are being diverted to foreign accounts in Obiang's circle. The most emblematic case is that of the president's son, known as Teodorín. Sentenced in France in October 2017 to three years in prison for money laundering and corruption, Teodorín has been vice president since 2016, on the way to succeeding his father.

Thus, while the Guinea of the powerful of the regime is the existence of sumptuous bank accounts abroad, in addition to movable and immovable property, a high percentage of Guineans have hardly any electricity, decent housing or schools that ensure a reasonable education for their children. Some remarkably private hospitals have been built, but the population does not have access to them and it is common to experience the theft of life in the jaws of death, as happened to me a few years ago. I was returning from my walks when I saw the wife of an uncle of mine with a child of almost a year and a half in her arms. He was still alive, but fainting. He was going somewhere in search of medical help, or financial help, or both. Then I became interested, and I ran home to secure the funds to meet the demands of those who would treat us in hospitals that might be better than those of Macías' time, but where they would only treat you if they knew you were going to pay. We went to the General Hospital of Malabo. We arrived and they put the child in a bed to offer him the care of his clearly failing health. But he did not survive. At the same time that they certified his death, and without any protocol, they offered him to us and, accompanied by his tearful mother, I carried him in my arms to cry in privacy. It was not possible for us to go by taxi because we could no longer hide the fact that that little Guinean was still alive.

As time passes inexorably, we hope that two things do not happen in Obiang's life: that he does not die soon, and that before his expected death he has placed someone from his blood family in the long-awaited seat of power...

JUN 18, 2019

With the feature film Guinea, the forbidden documentary , a team of Equatorial Guinean and Spanish filmmakers seeks to shed some light on the history of Equatorial Guinea fifty years after its independence as a Spanish colony.

“Fifty years ago, Equatorial Guinea was a province of Spain. Now, many people don’t even know where to find it on a map.” These two sentences begin the description of Guinea, the forbidden documentary , a feature film that seeks to shed some light on the opaque history of Equatorial Guinea when it has just celebrated half a century since its independence as a Spanish colony. A team of Spanish and Equatorial Guinean filmmakers is behind the first project on the Verkami crowdfunding platform that has allowed its promoters to remain anonymous “for security reasons.” Now that the first phase that will allow their work to go ahead has been completed, they agree to answer some questions for El Salto :

For the moment you have decided to remain anonymous. What are you exposing yourself to by leading this project?

We would like to take this opportunity to emphasise that it is not “an anonymous documentary” as has been said somewhere, nor will it be. We simply need to protect identities at this stage and once it is ready, part of the team will be present and another part will not. Unfortunately, it is a subject that cannot be worked on normally.

I assume that the history of Equatorial Guinea cannot be told in 70 minutes. What aspects have you focused on? What main objective would you say the documentary pursues?

We want the documentary to focus on the present, on the current situation in Guinea and its people, but at the same time to note the impact of history on our lives. We ask ourselves: why has apartheid in South Africa been talked about so often and we know nothing about the racist segregation that existed in Guinea during the Spanish colonisation? We understand that our job is simply to break the silence, to listen to the voice of those who know the most.

The information blackout on what is happening in Equatorial Guinea is total. Was it difficult to gather some information? How was that previous documentation phase?

Yes, the Obiang dictatorship has done the same as the previous dictatorships, exterminating journalism and the truth. In fact, there is not even reliable statistical data on such basic issues as the census of people living in the country. Lately, in the university environment there has been very powerful research and reflections that, unfortunately, have not managed to transcend the academic environment.

The Roig family (Mercadona), Miguel Ángel Moratinos, Francisco Hernando 'el Pocero' and Commissioner Villarejo are some of the names that appear in the trailer for the documentary. What was such a diverse group of Spaniards in Equatorial Guinea doing?

The opposition member Adolfo Obiang Bikó describes Equatorial Guinea as a family business with representatives in the United Nations. Equatorial Guinea is one of the few places in Africa where Spanish diplomacy has any relevance. Unfortunately, rather than democratising the country, some people have focused on business opportunities.

At 77, Teodoro Obiang has been in government for 40 years, making him the longest-serving leader on the continent. What are presidential elections like in Equatorial Guinea and why is the result always a seemingly overwhelming victory for the PDGE?

We are talking about a country without any kind of guarantees, where elections are held behind closed doors, without the media or electoral observers. There are people who will surely end up voting for Obiang out of fear, because they fear that their vote will somehow be revealed and there will be reprisals. As one opponent comments: “Not even God would have so much support in an election, how come he does?”

The discovery of large oil deposits in 1996 turned Equatorial Guinea almost overnight into one of the richest countries on the continent. Money from hydrocarbons has come to account for no less than 80% (in 2000) of the country's GDP. How has oil wealth affected the well-being of the population of a country that ranks 135th out of 188 countries in the Human Development Index?

Equatorial Guinea lives under an unbearable dictatorship that only benefits Obiang's immediate circle and large companies. This is one of the countries where inequality is most suffocating. Those closest to him party with Moët & Chandon, those who complain are sent to the army. The most shocking thing is to discover that many Guineans have become accustomed to living without freedom.

The latest Corruption Perception Index published by Transparency International places the country as one of the most corrupt (ranked 172 out of 180) in the public sector. To what extent is corruption structural among the ruling elites of Equatorial Guinea?

To the point that there are taxes that are paid directly into the bank accounts of ministers. It is one of the most crude and exaggerated forms of corruption that must exist. One of the most international writers in the country, Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel , describes the country as a “feudal regime”.

Devastating reports such as this latest one from Human Rights Watch have been documenting cases of systematic violation of Human Rights in the country for years. Some of the most recurrent ones denounce the imprisonment of political prisoners, arbitrary arrests and torture. Cases such as that of the cartoonist Ramón Esono are recent examples. How persecuted is freedom of expression in Equatorial Guinea ?

The situation is very extreme and, worst of all, there is no one to account for all the violence, arrests, torture, repression that exists... Obiang feels unpunished.

On what do they base their description of the country as “the African capitalist North Korea”?

Isolation, megalomania of its leaders, pre-eminence of the army, a single party, brutal persecution of dissidents, apparent religious freedom... Comparisons are always imprecise, but there are many points in common between the two countries, two of the most enigmatic totalitarian dictatorships in the world. The anniversary that Obiang celebrates every year is also very reminiscent of the cult of the North Korean leader. For weeks the media talks about the preparations, everyone is obliged to celebrate it, the television presenters congratulate him, smile and call him “your excellency”. It is delirious.

A seat on the United Nations Security Council, UNESCO prizes with his In fact , the international community is legitimising Obiang's regime and helping to clean up his image, as various organisations have denounced.

Absolutely. As Ramón Lobo wrote in 2012, thanks to oil, Obiang Nguema became a "presentable dictator". Of course, this is still happening today.

What would you say to those who oppose historical memory because it is about 'turning the page' and not 'stirring up the past'?

In recent days we have received many messages critical of our documentary, including some threats. What weighs most on us is that many of these comments show a lack of historical knowledge. One person told us that Spain has prospered in recent years and that if Equatorial Guinea has not, it is its fault. Comparing coloniser and colonised in this way is unusual.

Who and in what way reports on what happens on a daily basis in your country? Is there room in Equatorial Guinea for a local media outlet that is even minimally critical of the established power?

It is true that there is a very active diaspora, as are examples of the media Diario Rombe, Radio Macuto or associations such as Asodegue or EG Justice. But in the country the Internet is so expensive and so slow that it is not easy to breathe 'other air'. Social networks and certain websites are censored according to seasons and times. There are cracks and people who manage to say and do, but Obiang continues to impose his unique discourse with ease.

Every time Obiang gives an interview he leaves very serious headlines. In October 2018, speaking to TVE (Spanish Public Television) correspondent Luís Pérez, he declared that in Equatorial Guinea "there is practically no torture".

It is truly outrageous. Living in Equatorial Guinea is like reliving Francoism, but with a tropical climate.

They point to the Obiang regime, to those 'nostalgic for Francoism' and to the 'big media and the elites' as the three main actors not interested in their documentary coming to light. With this mix of detractors, it must not be easy to get such an ambitious work like this off the ground. Has any big media outlet or television channel been interested in the product you have in hand?

Not at the moment. In Spain we have found that there is no television channel that wants to co-produce, so we need popular support to make it possible. Pressures and difficulties with financing are always present when dealing with a subject like this. Look at what happened, for example, with 'Memoria Negra' , a documentary about Equatorial Guinea that TVE co-produced but did not want to broadcast and that the Guinean government did not authorise to be filmed in the country. The team from “Palmeras en la nieve” (Palmeras in the Snow), a film that was released in 2015 with a budget of 10 million euros, was also unable to film in Guinea. We don’t even have enough money for what they spent on catering.

In just 11 days they have managed to raise the 5,000 euros for the first phase. It seems that through the micro-funding route the reception has been very good.

We are very grateful. There are many people who have felt called upon and have mobilized. We need the maximum support to give it the strength it deserves and not fall by the wayside. And that path involves investing money. Without going any further, each fragment of the NO-DO that we would like to include costs about 2,500 euros per minute.

In this second phase of financing they are looking to double the research time and finance the translation and subtitles that allow each person to speak in their mother tongue (Bubi, Pichi, Annobonense Creole, Fang…). How will you make the project grow from now on?

We have more things in mind. Creating a website with extra videos, an educational suitcase for schools, enabling entities to schedule a showing in their spaces... At this time, any contribution will be of great help. Hopefully, with the campaign, a miracle will happen to us, like the people who did with “El silencio de otros” (The Silence of Others), who received great support and ended up being broadcast on public television with great audience success.

Thank you for your attention and good luck with the project.

Human rights activist Anacleto Micha Ndong Nlang initially faced the same charges over the same event, even though he was arrested four days before the others (when he visited the office to see whether party supporters under siege needed assistance). His charges were subsequently changed to “contempt against authority” and his case sent to ordinary court. On 19 May, he was sentenced to six months in prison and fined XAF 100,000 (around EUR 152). He was released on 23 June, some nine months after his arrest.

The death of Julio Obama occurred less than two weeks after Spain’s High Court opened an investigation against Carmelo Ovono Obiang, the son of the Equatorial Guinean president, and two other officials. They were accused of the alleged abduction and torture of four Equatorial Guinean nationals, including Julio Obama and another dual national as well as two other residents of Spain, all of whom were MLGE3R members.

On 16 February, the European Parliament adopted a resolution condemning “political persecution and repression of political opponents” in Equatorial Guinea, as well as the death of Julio Obama while in custody, and requesting an independent international investigation. In March, all three officials failed to appear at the Spanish High Court. The court ordered that Julio Obama’s body be taken back to Spain, but this was ignored. In April, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Equatorial Guinea informed the Spanish government that it had opened an investigation into the alleged torture of the four men, thereby claiming jurisdiction over the matter. Court proceedings in Spain were still pending at the end of the year.

www.amnesty.org

www.amnesty.org

Guinea Ecuatorial - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

Equatorial Guinea - Wikipedia

EQUATORIAL GUINEA

LIFE IN THE JAWS OF DEATH :

The author, an Equatorial Guinean writer, makes a historical review of the 50 years of independence of Equatorial Guinea, through the regimes of Macías and Obiang.17 NOV 2018

Teodoro Obiang

1. Innocent childhood

When we were growing up, we were told that among the peoples of Equatorial Guinea there were some people who liked the flesh of others. And when we learned to read and learned that the whites had been among us, we learned that they also left written records that when they set foot on our lands, someone told them to be careful, that a certain people who waited in the thick of the forest had the odious custom of wishing death on people who had desirable flesh. Since that stuck in our minds, we wanted to begin this brief reminder like that.2. Everything fell apart

But very soon that innocence was shattered and we opened our eyes to the terrifying presence of a former 'emancipated' [the emancipated constituted the black population assimilated to the whites] whom historical events brought to the presidency of the country after five years of merely formal autonomy. That man, Francisco Macías Nguema, soon renounced his collaborationist past and sought his African roots, a personal change that he imposed by means of slaps, beatings and death throughout Equatorial Guinea. It was then that we discovered, through his henchmen and the immense court of flatterers, that we had lived through 200 years of slavery and pillage and that we were redeemed thanks to the wise guidance of the only miracle of Equatorial Guinea, a great master of traditional art and culture, the honourable and great comrade Masié Nguema Biyogo Ñengue Ndong.GLOSSARY:

Francisco Macías Nguema —also known as Masié Nguema Biyogo— was the first president of independent Equatorial Guinea, a position he held between 1968 and 1979, the year in which he was overthrown by his nephew Teodoro Obiang. Despite having participated in the previous administration, Macías claimed to be a nationalist. He also said he admired Hitler and, while he lso sought certain ideological harmony within the context marked by the Cold War, and in a purely effectual gesture, his Single National Party (PUN) added an opportunistic T, for "workers", with which Macías, ignorant of the rudiments of the Marxism, tried to establish ties with Cuba and the USSR.

After being ousted from power, he was executed on 29 September 1979.

Public praise was instituted, poverty became suffocating, hospitals became death throes, the Public Administration ceased to exist and a great cloak of darkness covered everything, a silent chaos that was broken by the screams of those tortured in Blay Beach, that prison that became famous. These were the years, shortly after independence, when those convicted for having been declared subversives were subjected to the torture known as Ethiopian torture . This was suffered by those who had not managed to leave the country or those who had not died before from some painful story.

GLOSSARY:

The 'Ethiopian' torture consisted of tying two sticks to the victim's calf and squeezing the ends. It was one of a wide range of practices that included machetes, electric shocks or blows with red-hot iron bars. Political prisoners were sometimes forced to dance while being beaten. Before overthrowing his uncle, Teodoro Obiang Nguema held various positions during his regime, including that of warden of Blay Beach. The dictator, who will celebrate 40 years at the head of the country next year, has based his continuity on oil reserves, obtaining the complicity of foreign powers despite the embezzlement of fortunes and the perennial poverty of the population.