Eltitoguay

Well-known member

Período especial - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

Special Period - Wikipedia

Dirty Havana Trilogy

Summary and synopsis of Dirty Havana Trilogy, by Pedro Juan Gutiérrez :

"This is the testimony of a disbelieving Havana resident, during the Special Period of Cuba :A man who returns exhausted from a long journey that ultimately led him nowhere. But he is not pessimistic. Pedro Juan knows that he has to move forward. And the best way to do so is smiling, with a drink of rum, music and sex. Pedro Juan Gutiérrez catharses in this hard and largely autobiographical book, which brings together three collections of short stories: "Anclado en tierra de nadie", "Nada que hacer" and "Sabor a mí".

A strong and tight language is the only one capable of expressing the rage of someone who lives in the vortex of the hurricane. Pedro Juan lives on the edge of the precipice. Marginal, although his hovel is in the heart of Havana today. He dissects his surroundings with the skill of an expert surgeon. Without fear he plunges his sharp scalpel, digs into the entrails, and turns everything upside down, disrespectfully: sex, hunger, politics, eroticism, disenchantment, yearnings, rum and good humor.

Written at a relentless pace, halfway between tropical exuberance and the black desolation of a Bukowski, the "Dirty Havana Trilogy" is a dazzling set of stories orchestrated like a novel. Tough, moving and true, they reveal to us a writer of pure breed, a relentless chronicler of a country and times that are contradictory, terrible, fascinating."

Pedro Juan Gutiérrez in Cuba.

Pedro Juan Gutiérrez - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

Pedro Juan Gutiérrez - Wikipedia

Pedro Juan Gutiérrez (Matanzas, Cuba, 1950) is internationally recognized as one of the most talented writers of current Hispanic American narrative. His Centro Habana Cycle has been published in its entirety by Anagrama, and has appeared in other languages in more than twenty countries: Dirty Havana Trilogy (also published in individual titles: Anchored in No Man's Land , Nothing to Do and Taste of Me ), The King of Havana (which has been adapted to film by the prestigious director Agustí Villaronga), Tropical Animal (Alfonso García-Ramos Prize), The Insatiable Spider Man and Dog Meat (Sur del Mundo Narrative Prize). He has also published the novels Our GG in Havana , The Snake's Nest. Memoirs of the Ice Cream Man's Son , Fabian and Chaos and Stoic and Frugal , as well as the book of self-interviews Dialogue with my Shadow. On the Writer's Craft, with Anagrama . He lives in Havana and devotes himself exclusively to literature and painting. His most recent work is the book of short stories Mecánica popular .

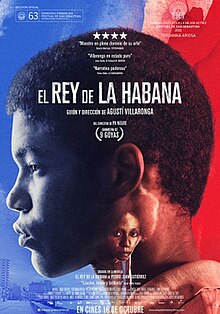

The King of Havana

Summary and synopsis of The King of Havana, by Pedro Juan Gutiérrez :

This is the story of a young teenager thrown into the streets of Havana in the nineties, during the Special Period of Cuba :A novel based on real events, written crudely, without embellishments, in the best tradition of dirty realism. Pedro Juan Gutiérrez continues here his saga about the Caribbean city and its poorest and most marginal people: beggars, prostitutes, transvestites, street vendors, rogues, drunks, the inhabitants of an abandoned and ruined building, penniless guys, hungry, always on the verge of death. A terrible and apocalyptic fauna.

“This is the voice of the voiceless,” says the author about his characters. “Those who have to scratch the earth every day to find something to eat, have neither time nor energy for anything else. Their only goal is to survive. Whatever it takes. Any way. They themselves don’t know why or what for. They insist on surviving one more day. Just that.” Despite everything, love, sex and tenderness mark the lives of these tormented beings.

Following his dazzling debut with Havana Trilogy, hailed by critics as one of the most impressive revelations in recent Latin American literature, this novel confirmed the many hopes placed in Pedro Juan Gutiérrez.

«Sex and survival are intertwined in the same inseparable texture... The best thing is the laconic power of the style, the impeccable verbal forcefulness, the brutal dryness, as well as the capture of colloquial registers» (Miguel García-Posada, El País).

The Agustí Villaronga's adapted film:

The King of Havana - Wikipedia

.

.

.

.

Last edited: