In the old days they said to use aspirin to reverse sex , I never tried itPlant hormone

Salicylic acid is a phenolic phytohormone, and is found in plants with roles in plant growth and development, photosynthesis, transpiration, and ion uptake and transport.[53] Salicylic acid is involved in endogenous signaling, mediating plant defense against pathogens.[54] It plays a role in the resistance to pathogens (i.e. systemic acquired resistance) by inducing the production of pathogenesis-related proteins and other defensive metabolites.[55] SA's defense signaling role is most clearly demonstrated by experiments which do away with it: Delaney et al. 1994, Gaffney et al. 1993, Lawton et al. 1995, and Vernooij et al. 1994 each use Nicotiana tabacum or Arabidopsis expressing nahG, for salicylate hydroxylase. Pathogen inoculation did not produce the customarily high SA levels, SAR was not produced, and no pathogenesis-related (PR) genes were expressed in systemic leaves. Indeed, the subjects were more susceptible to virulent – and even normally avirulent – pathogens.[53]

Exogenously, salicylic acid can aid plant development via enhanced seed germination, bud flowering, and fruit ripening, though too high of a concentration of salicylic acid can negatively regulate these developmental processes.[56]

The volatile methyl ester of salicylic acid, methyl salicylate, can also diffuse through the air, facilitating plant-plant communication.[57] Methyl salicylate is taken up by the stomata of the nearby plant, where it can induce an immune response after being converted back to salicylic acid.[58]

Signal transduction

A number of proteins have been identified that interact with SA in plants, especially salicylic acid binding proteins (SABPs) and the NPR genes (nonexpressor of pathogenesis-related genes), which are putative receptors.[59

Salicylic acid - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

Clones, Mother plants, How to "Clean" cuttings!

- Thread starter Thread starter acespicoli

- Start date Start date

-

- Tags Tags

- clone

Spindle apparatus - Wikipedia

Plant organogenesis

In plants, organogenesis occurs continuously and only stops when the plant dies. In the shoot, the shoot apical meristems regularly produce new lateral organs (leaves or flowers) and lateral branches. In the root, new lateral roots form from weakly differentiated internal tissue (e.g. the xylem-pole pericycle in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana). In vitro and in response to specific cocktails of hormones (mainly auxins and cytokinins), most plant tissues can de-differentiate and form a mass of dividing totipotent stem cells called a callus. Organogenesis can then occur from those cells. The type of organ that is formed depends on the relative concentrations of the hormones in the medium. Plant organogenesis can be induced in tissue culture and used to regenerate plants.[7]Plant embryos

Main article: Plant embryonic developmentFurther information: Sporophyte

The inside of a Ginkgo seed, showing the embryo

Flowering plants (angiosperms) create embryos after the fertilization of a haploid ovule by pollen. The DNA from the ovule and pollen combine to form a diploid, single-cell zygote that will develop into an embryo.[21] The zygote, which will divide multiple times as it progresses throughout embryonic development, is one part of a seed. Other seed components include the endosperm, which is tissue rich in nutrients that will help support the growing plant embryo, and the seed coat, which is a protective outer covering. The first cell division of a zygote is asymmetric, resulting in an embryo with one small cell (the apical cell) and one large cell (the basal cell).[22] The small, apical cell will eventually give rise to most of the structures of the mature plant, such as the stem, leaves, and roots.[23] The larger basal cell will give rise to the suspensor, which connects the embryo to the endosperm so that nutrients can pass between them.[22] The plant embryo cells continue to divide and progress through developmental stages named for their general appearance: globular, heart, and torpedo. In the globular stage, three basic tissue types (dermal, ground, and vascular) can be recognized.[22] The dermal tissue will give rise to the epidermis or outer covering of a plant,[24] ground tissue will give rise to inner plant material that functions in photosynthesis, resource storage, and physical support,[25] and vascular tissue will give rise to connective tissue like the xylem and phloem that transport fluid, nutrients, and minerals throughout the plant.[26] In heart stage, one or two cotyledons (embryonic leaves) will form. Meristems (centers of stem cell activity) develop during the torpedo stage, and will eventually produce many of the mature tissues of the adult plant throughout its life.[22] At the end of embryonic growth, the seed will usually go dormant until germination.[27] Once the embryo begins to germinate (grow out from the seed) and forms its first true leaf, it is called a seedling or plantlet.[28]

Plants that produce spores instead of seeds, like bryophytes and ferns, also produce embryos. In these plants, the embryo begins its existence attached to the inside of the archegonium on a parental gametophyte from which the egg cell was generated.[29] The inner wall of the archegonium lies in close contact with the "foot" of the developing embryo; this "foot" consists of a bulbous mass of cells at the base of the embryo which may receive nutrition from its parent gametophyte.[30] The structure and development of the rest of the embryo varies by group of plants.[31]

Since all land plants create embryos, they are collectively referred to as embryophytes (or by their scientific name, Embryophyta). This, along with other characteristics, distinguishes land plants from other types of plants, such as algae, which do not produce embryos.[32]

Attachments

Last edited:

They are also involved in cell division (by mitosis and meiosis) and are the main constituents of mitotic spindles, which are used to pull eukaryotic chromosomes apart.

Microtubule - Wikipedia

Last edited:

Many thanks for adding so much to this site. Every thing you post has educational value. Have been growing plants across multiple species for 50 plus years and still don't know shit.

On the topic of cloning, just try to keep it simple. Conditions vary so widely, no one way is the best. For me, a wet perlite-vermiculite mix in cells under a dome at 70 deg under T8's. Will mist the lid daily after the 1st week and usually see roots in the 14 -21 day span. I do clip leaves and make my final cut under water but don't use rooting agents.

On the topic of cloning, just try to keep it simple. Conditions vary so widely, no one way is the best. For me, a wet perlite-vermiculite mix in cells under a dome at 70 deg under T8's. Will mist the lid daily after the 1st week and usually see roots in the 14 -21 day span. I do clip leaves and make my final cut under water but don't use rooting agents.

Plants 2023, 12(5), 1196; https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12051196

Polyacrylamide Hydrogel Enriched with Amber for In Vitro Plant Rooting

They showed that the synthesized hydrogels have physicochemical and rheological parameters similar to those of the standard agar media.

Callus (cell biology) - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

Callus (cell biology) - Wikipedia

Ground tissue

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Flax stem cross-section:

The ground tissue of plants includes all tissues that are neither dermal nor vascular. It can be divided into three types based on the nature of the cell walls. This tissue system is present between the dermal tissue and forms the main bulk of the plant body.

- Parenchyma cells have thin primary walls and usually remain alive after they become mature. Parenchyma forms the "filler" tissue in the soft parts of plants, and is usually present in cortex, pericycle, pith, and medullary rays in primary stem and root.

- Collenchyma cells have thin primary walls with some areas of secondary thickening. Collenchyma provides extra mechanical and structural support, particularly in regions of new growth.

- Sclerenchyma cells have thick lignified secondary walls and often die when mature. Sclerenchyma provides the main structural support to the plant.[1]

- Aerenchyma cells are found in aquatic plants. They are also known to be parenchyma cells with large air cavities surrounded by irregular cells which form columns called trabeculae.

Parenchyma

Parenchyma is a versatile ground tissue that generally constitutes the "filler" tissue in soft parts of plants. It forms, among other things, the cortex (outer region) and pith (central region) of stems, the cortex of roots, the mesophyll of leaves, the pulp of fruits, and the endosperm of seeds. Parenchyma cells are often living cells and may remain meristematic, meaning that they are capable of cell division if stimulated. They have thin and flexible cellulose cell walls and are generally polyhedral when close-packed, but can be roughly spherical when isolated from their neighbors. Parenchyma cells are generally large. They have large central vacuoles, which allow the cells to store and regulate ions, waste products, and water. Tissue specialised for food storage is commonly formed of parenchyma cells.

Cross section of a leaf showing various ground tissue types

Parenchyma cells have a variety of functions:

- In leaves, they form two layers of mesophyll cells immediately beneath the epidermis of the leaf, that are responsible for photosynthesis and the exchange of gases.[2] These layers are called the palisade parenchyma and spongy mesophyll. Palisade parenchyma cells can be either cuboidal or elongated. Parenchyma cells in the mesophyll of leaves are specialised parenchyma cells called chlorenchyma cells (parenchyma cells with chloroplasts). Parenchyma cells are also found in other parts of the plant.

- Storage of starch, protein, fats, oils and water in roots, tubers (e.g. potatoes), seed endosperm (e.g. cereals) and cotyledons (e.g. pulses and peanuts)

- Secretion (e.g. the parenchyma cells lining the inside of resin ducts)

- Wound repair [citation needed] and the potential for renewed meristematic activity

- Other specialised functions such as aeration (aerenchyma) provides buoyancy and helps aquatic plants float.

- Chlorenchyma cells carry out photosynthesis and manufacture food.

Shapes of parenchyma:

- Polyhedral (found in pallisade tissue of the leaf)

- Spherical

- Stellate (found in stem of plants and have well-developed air spaces between them)

- Elongated (also found in pallisade tissue of leaf)

- Lobed (found in spongy and pallisade mesophyll tissue of some plants)

Collenchyma

Cross section of collenchyma cells

Cross section of collenchyma cellsCollenchyma tissue is composed of elongated cells with irregularly thickened walls. They provide structural support, particularly in growing shoots and leaves (as seen, for example, the resilient strands in stalks of celery). Collenchyma cells are usually living, and have only a thick primary cell wall[6] made up of cellulose and pectin. Cell wall thickness is strongly affected by mechanical stress upon the plant. The walls of collenchyma in shaken plants (to mimic the effects of wind etc.), may be 40–100% thicker than those not shaken.

There are four main types of collenchyma:

- Angular collenchyma (thickened at intercellular contact points)

- Tangential collenchyma (cells arranged into ordered rows and thickened at the tangential face of the cell wall)

- Annular collenchyma (uniformly thickened cell walls)

- Lacunar collenchyma (collenchyma with intercellular spaces)

The first use of "collenchyma" (/kəˈlɛŋkɪmə, kɒ-/[7][8]) was by Link (1837) who used it to describe the sticky substance on Bletia (Orchidaceae) pollen. Complaining about Link's excessive nomenclature, Schleiden (1839) stated mockingly that the term "collenchyma" could have more easily been used to describe elongated sub-epidermal cells with unevenly thickened cell walls.[9]

Sclerenchyma

Sclerenchyma is the tissue which makes the plant hard and stiff. Sclerenchyma is the supporting tissue in plants. Two types of sclerenchyma cells exist: fibers cellular and sclereids. Their cell walls consist of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Sclerenchyma cells are the principal supporting cells in plant tissues that have ceased elongation. Sclerenchyma fibers are of great economic importance, since they constitute the source material for many fabrics (e.g. flax, hemp, jute, and ramie).Unlike the collenchyma, mature sclerenchyma is composed of dead cells with extremely thick cell walls (secondary walls) that make up to 90% of the whole cell volume. The term sclerenchyma is derived from the Greek σκληρός (sklērós), meaning "hard." It is the hard, thick walls that make sclerenchyma cells important strengthening and supporting elements in plant parts that have ceased elongation. The difference between sclereids is not always clear: transitions do exist, sometimes even within the same plant.

Fibers

Cross section of sclerenchyma fibers

Fibers or bast are generally long, slender, so-called prosenchymatous cells, usually occurring in strands or bundles. Such bundles or the totality of a stem's bundles are colloquially called fibers. Their high load-bearing capacity and the ease with which they can be processed has since antiquity made them the source material for a number of things, like ropes, fabrics and mattresses. The fibers of flax (Linum usitatissimum) have been known in Europe and Egypt for more than 3,000 years, those of hemp (Cannabis sativa) in China for just as long. These fibers, and those of jute (Corchorus capsularis) and ramie (Boehmeria nivea, a nettle), are extremely soft and elastic and are especially well suited for the processing to textiles. Their principal cell wall material is cellulose.

Contrasting are hard fibers that are mostly found in monocots. Typical examples are the fiber of many grasses, Agave sisalana (sisal), Yucca or Phormium tenax, Musa textilis and others. Their cell walls contain, besides cellulose, a high proportion of lignin. The load-bearing capacity of Phormium tenax is as high as 20–25 kg/mm², the same as that of good steel wire (25 kg/ mm²), but the fibre tears as soon as too great a strain is placed upon it, while the wire distorts and does not tear before a strain of 80 kg/mm². The thickening of a cell wall has been studied in Linum.[citation needed] Starting at the centre of the fiber, the thickening layers of the secondary wall are deposited one after the other. Growth at both tips of the cell leads to simultaneous elongation. During development the layers of secondary material seem like tubes, of which the outer one is always longer and older than the next. After completion of growth, the missing parts are supplemented, so that the wall is evenly thickened up to the tips of the fibers.

Fibers usually originate from meristematic tissues. Cambium and procambium are their main centers of production. They are usually associated with the xylem and phloem of the vascular bundles. The fibers of the xylem are always lignified, while those of the phloem are cellulosic. Reliable evidence for the fibre cells' evolutionary origin from tracheids exists.[10] During evolution the strength of the tracheid cell walls was enhanced, the ability to conduct water was lost and the size of the pits was reduced. Fibers that do not belong to the xylem are bast (outside the ring of cambium) and such fibers that are arranged in characteristic patterns at different sites of the shoot. The term "sclerenchyma" (originally Sclerenchyma) was introduced by Mettenius in 1865.[11]

Sclereids

Fresh mount of a sclereid

Long, tapered sclereids supporting a leaf edge in Dionysia kossinskyi

Sclereids are the reduced form of sclerenchyma cells with highly thickened, lignified walls.

They are small bundles of sclerenchyma tissue in plants that form durable layers, such as the cores of apples and the gritty texture of pears (Pyrus communis). Sclereids are variable in shape. The cells can be isodiametric, prosenchymatic, forked or elaborately branched. They can be grouped into bundles, can form complete tubes located at the periphery or can occur as single cells or small groups of cells within parenchyma tissues. But compared with most fibres, sclereids are relatively short. Characteristic examples are brachysclereids or the stone cells (called stone cells because of their hardness) of pears and quinces (Cydonia oblonga) and those of the shoot of the wax plant (Hoya carnosa). The cell walls fill nearly all the cell's volume. A layering of the walls and the existence of branched pits is clearly visible. Branched pits such as these are called ramiform pits. The shell of many seeds like those of nuts as well as the stones of drupes like cherries and plums are made up from sclereids.

These structures are used to protect other cells.

References

^ Mauseth 2012, pp. 98–103.- ^ Jump up to:a b "Leaves". Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2012-05-18.

- ^ Jeffree CE, Read N, Smith JAC and Dale JE (1987). Water droplets and ice deposits in leaf intercellular spaces: redistribution of water during cryofixation for scanning electron microscopy. Planta 172, 20-37

- ^ Hill, J. Ben; Overholts, Lee O; Popp, Henry W. Grove Jr., Alvin R. Botany. A textbook for colleges. Publisher: MacGraw-Hill 1960[page needed]

- ^ Evert, Ray F; Eichhorn, Susan E. Esau's Plant Anatomy: Meristems, Cells, and Tissues of the Plant Body: Their Structure, Function, and Development. Publisher: Wiley-Liss 2006. ISBN 978-0-471-73843-5[page needed]

- ^ Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B. (2008). Biology (8th ed.). Pearson Education, Inc. pp. 744–745. ISBN 978-0-321-54325-7.

- ^ "collenchyma". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- ^ "collenchyma". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-10-29.

- ^ Leroux O. 2012. Collenchyma: a versatile mechanical tissue with dynamic cell walls. Annals of Botany 110 (6): 1083-98.

- ^ Carlquist, Sherwin (2001). Comparative Wood Anatomy: Systematic, Ecological, and Evolutionary Aspects of Dicotyledon Wood. Springer Series in Wood Science. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-04578-7. ISBN 978-3-642-07438-7.

- ^ Mettenius, G. 1865. Über die Hymenophyllaceae. Abhandlungen der Mathematisch-Physischen Klasse der Königlich-Sächsischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften 11: 403-504, pl. 1-5. link.

Further reading

Mauseth, James D. (2012). Botany : An Introduction to Plant Biology (5th ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-1-4496-6580-7.- Moore, Randy; Clark, W. Dennis; and Vodopich, Darrell S. (1998). Botany (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-697-28623-1.

- Chrispeels MJ, Sadava DE. (2002) Plants, Genes and Crop Biotechnology. Jones and Bartlett Inc., ISBN 0-7637-1586-7

Ground tissue - Wikipedia

Cloning Cannabis Step by Step

Step 1: Prepare the clone

Prepare a cup or measuring cup with filtered water and the appropriate amount of Clonex Solution. Make sure it is large enough to hold all of the cuttings you want to take. Using clean and sharp scissors/blades, take cuttings from your donor plant. Make sure you are cutting from the bottom and as close to the stem as possible. They should have three to four nodes on them. Cut the remaining lower nodes off if needed. Strip off all large fan leaves not associated with your nodes as well. Clip all of the remaining leaves at the tips. Cutting leaf tips reduces transpiration. Make clean, sharp cuts for the health of your plants. Place the URCs (unrooted cuttings) in your cup with the prepared Clonex Solution stem down.

Continue taking cuts like this until you are finished and ready to move on to step two.

Step 2: Shaping the clone

Take a URC from your cup and measure the cannabis clone against a measuring stick/the blade of your scissors will do. This keeps the cannabis clones uniform in height for a more even canopy. Cut the excess off at a 45-degree angle. This will increase the surface area of the exposed tissue. Increasing the area from which roots can develop (although roots can form from differentiated tissue, it is better to expose the undifferentiated cells (stem cells) for root development).

Step 3: Prepare for rooting

Hold the cannabis clone in your hand bottom up. In your opposite hand, use your scalpel to mark or scrap the surface near the cut end. This helps root development. Scrape just the outside layers of tissue. Cutting the stem at a 45-degree angle allows the rooting hormone to contact more surface area of the plant’s cells, thus increasing rooting chances.

Step 4: Applying rooting agent

Pour a small amount of Clonex into a small shotglass. Replace the cap. Never stick anything into a bottle like Clonex that makes contact with plants. Doing so will contaminate the entire bottle. Use the pipette to suck up some Clonex. Using the pipette, apply a thin line to the area you just prepared with the scalpel. Use the pipette to spread the Clonex gel all over the prepared area. This ensures you do not over-apply or waste Clonex. Using too much can kill the cutting before it can root, wasting resources. LESS IS MORE.

Step 5: Planting the unrooted cannabis clone

Take your cannabis clone and place it in the prepared hole in the rooting cube. Push it until the prepared area you want to root is entirely enclosed in the cube. Do not push the bottom out of the cube. Place the cube in your tray, insert and repeat the process until complete.

Cover all of your cuttings with the humidity dome and place the entire tray on the seedling mat. Set this under a cool blue 25–50-watt T-5 bulb. A stronger light is not preferred. The cool blue spectrum also aids in rooting. Plug in the seedling mat and set the temperature to 77 degrees with a +/- 2.5-degree variance. Put 300 to 400 mL of water in the bottom of the plant tray. Ensure that the bottom of the inserts holding your clones does not touch the water. The seed mat will heat the water in the tray and form a good warm, humid environment, preventing the need for spraying cannabis clones for humidity control. Leave it alone for three days. On the fourth day, open the dome to exchange the air by just pushing the dome's edge onto the tray, so it sits unevenly. Open the dome’s air vents to make a flow of air go into the dome. Keep the water in the tray from evaporating completely. Continue this for approximately 14 days or until all cubes have roots growing down into the water in the tray under the inserts. Your cannabis clones are now ready for transplant.

-seedsman

Step 1: Prepare the clone

Prepare a cup or measuring cup with filtered water and the appropriate amount of Clonex Solution. Make sure it is large enough to hold all of the cuttings you want to take. Using clean and sharp scissors/blades, take cuttings from your donor plant. Make sure you are cutting from the bottom and as close to the stem as possible. They should have three to four nodes on them. Cut the remaining lower nodes off if needed. Strip off all large fan leaves not associated with your nodes as well. Clip all of the remaining leaves at the tips. Cutting leaf tips reduces transpiration. Make clean, sharp cuts for the health of your plants. Place the URCs (unrooted cuttings) in your cup with the prepared Clonex Solution stem down.

Continue taking cuts like this until you are finished and ready to move on to step two.

Step 2: Shaping the clone

Take a URC from your cup and measure the cannabis clone against a measuring stick/the blade of your scissors will do. This keeps the cannabis clones uniform in height for a more even canopy. Cut the excess off at a 45-degree angle. This will increase the surface area of the exposed tissue. Increasing the area from which roots can develop (although roots can form from differentiated tissue, it is better to expose the undifferentiated cells (stem cells) for root development).

Step 3: Prepare for rooting

Hold the cannabis clone in your hand bottom up. In your opposite hand, use your scalpel to mark or scrap the surface near the cut end. This helps root development. Scrape just the outside layers of tissue. Cutting the stem at a 45-degree angle allows the rooting hormone to contact more surface area of the plant’s cells, thus increasing rooting chances.

Step 4: Applying rooting agent

Pour a small amount of Clonex into a small shotglass. Replace the cap. Never stick anything into a bottle like Clonex that makes contact with plants. Doing so will contaminate the entire bottle. Use the pipette to suck up some Clonex. Using the pipette, apply a thin line to the area you just prepared with the scalpel. Use the pipette to spread the Clonex gel all over the prepared area. This ensures you do not over-apply or waste Clonex. Using too much can kill the cutting before it can root, wasting resources. LESS IS MORE.

Step 5: Planting the unrooted cannabis clone

Take your cannabis clone and place it in the prepared hole in the rooting cube. Push it until the prepared area you want to root is entirely enclosed in the cube. Do not push the bottom out of the cube. Place the cube in your tray, insert and repeat the process until complete.

Cover all of your cuttings with the humidity dome and place the entire tray on the seedling mat. Set this under a cool blue 25–50-watt T-5 bulb. A stronger light is not preferred. The cool blue spectrum also aids in rooting. Plug in the seedling mat and set the temperature to 77 degrees with a +/- 2.5-degree variance. Put 300 to 400 mL of water in the bottom of the plant tray. Ensure that the bottom of the inserts holding your clones does not touch the water. The seed mat will heat the water in the tray and form a good warm, humid environment, preventing the need for spraying cannabis clones for humidity control. Leave it alone for three days. On the fourth day, open the dome to exchange the air by just pushing the dome's edge onto the tray, so it sits unevenly. Open the dome’s air vents to make a flow of air go into the dome. Keep the water in the tray from evaporating completely. Continue this for approximately 14 days or until all cubes have roots growing down into the water in the tray under the inserts. Your cannabis clones are now ready for transplant.

-seedsman

FilthyDank'Wasteman'Fabul

Active member

One thing we did in the greenhouse, wether rooting a herbacous or woody perennial, we always left a growing node at the bottom of the cutting, instead of the unspecialized stem as the bottom cut tip

Interesting, been experimenting used to do some clones in solo cups aOne thing we did in the greenhouse, wether rooting a herbacous or woody perennial, we always left a growing node at the bottom of the cutting, instead of the unspecialized stem as the bottom cut tip

long time ago, then in a fogponic system that worked quite well. The more recent experience was a very neglected tray.

As you say the only ones that took well, had the node. Now there are certain details to that woody type stems drug type cannabis, hollow stem hemp type plants.

Well maybe you see where this is going as im sure your already onto. Bamboo type segments

AI Overview

Learn more

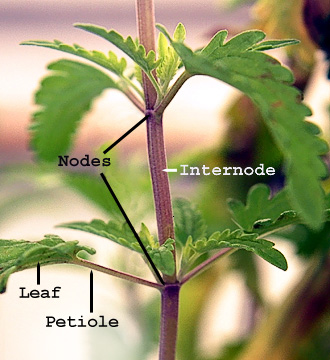

The segments of bamboo are called internodes, and they are separated by nodes. The nodes are the rings that can be seen along the length of a bamboo culm.

Nodes

- Function: Nodes are essential for the growth and development of the bamboo plant. They are the points where branches, leaves, and roots emerge.

- Location: Nodes are diaphragms that separate the hollow culms into compartments.

- Appearance: Nodes are visible as rings on the bamboo culm.

- Structure: Each node has two rings, the sheath ring and the stem ring.

- Function: Internodes provide bamboo with its segmented appearance.

- Structure: Internodes are usually hollow inside and form bamboo cavities.

- Length: The length of internodes varies depending on the bamboo species and the location on the culm.

Growth

- Height: The bamboo culm grows taller each year, primarily at the nodes.

- Nutrient distribution: Nodes act as barriers to prevent the downward flow of water and nutrients.

- Rhizomes: New bamboo roots and rhizomes grow from the node area.

Generative AI is experimental.

Last edited:

You brought the thunder, this is it I have been waiting for this !!!One thing we did in the greenhouse, wether rooting a herbacous or woody perennial, we always left a growing node at the bottom of the cutting, instead of the unspecialized stem as the bottom cut tip

The genius is in how and where this cut is made.

Its a secret that isnt shared by anyone that I have seen in academic work or in canna culture how to clone.

Believe me I have been looking everywhere.

Nodes

- Function: Nodes are essential for the growth and development of the bamboo plant. They are the points where branches, leaves, and roots emerge.

thanks for sharing it.

thanks for sharing it.Node cuts and how to make a compound node cut exposing a maximum of surface area to a node cut for the most vigorous root system to form

A.....................................................B.................................................C............?

Lets call these?

C is my preferred cut, the base of that cut can be angled in 4 different directions to expose more rooting flesh

Hope to get some photos up as time allows, anyone else doing the same feel free to share photos etc if you have them

Also there is the fact that the nodes segment is still attached providing a physical barrier to retain water and prevent contamination

The picture C. still needs work to perfect it.

Cutting (plant) - Wikipedia

Plant stem - Wikipedia

This above-ground stem of Polygonum has lost its leaves, but is producing adventitious roots from the nodes.

When we take this cutting we would like a fully functioning plant / less the roots of course

People make fancy uts with razors etc some of the best roots are from crushed stems

Some more lightning to go with the thunder ?

Will do some pictures soon to shine some more light on this subject

Last edited:

I hope that everyone here takes the time to look this thread over and have a go at it of their own and post findings etcI'm not sure about that last article. We need to know how consistent the grower is, before we can see if their treatments did anything. To judge consistency, the experiament was run twice. On the second run, everything rooted. Treated or just wet, is was 100%. However, on the first run, some were 0%. Exactly the same experiment, done to prove consistency, actually shows us there is an absolute worst case scenario. If we remove the two odd results, The A4 treatment is comparable to no treatment. It all becomes so close, as to become meaningless. When there is such low confidence, due to the water inconsistencies. Then we turn to the pictures of the roots, and the water looks best to me. Though standing in RO for 24h just seems crazy. There should be a test of not messing about at all.

FilthyDank'Wasteman'Fabul

Active member

People who keep things like this a secret (intentionally) are pure pigs man

Why people keep secrets that prevent others from success it really peeves me

And when people will scrape off the epidermis or split the cutting like an uncooked sausage to encourage roots. Makes me wince. I dont even like rooting hormone, its unnecessary, i have heard people dipping and soaking fresh cuts in liquid seaweed extract, i much prefer something like this...

Either way if the cutting is a good one and you provide high humidity around where you want roots, the hormones in the plant will root as fast if you have practice

I put cuttings in pure sand, put the pot with the sand in a slightly larger container, with leca on the bottom and sides of the larger container, lining the outside of the plant pot with the cuttings, it creates humidity in the prospective rootzone and roots things really fast compared to water rooting and using just the substrate and putting in a propagator, i use a propagator too but having an extra layer of very high humidity around the roots and rooting medium speeds things up so much, the cutting roots in times comprable to using rooting hormone (but without the nasty chemicals)

Why people keep secrets that prevent others from success it really peeves me

And when people will scrape off the epidermis or split the cutting like an uncooked sausage to encourage roots. Makes me wince. I dont even like rooting hormone, its unnecessary, i have heard people dipping and soaking fresh cuts in liquid seaweed extract, i much prefer something like this...

Either way if the cutting is a good one and you provide high humidity around where you want roots, the hormones in the plant will root as fast if you have practice

I put cuttings in pure sand, put the pot with the sand in a slightly larger container, with leca on the bottom and sides of the larger container, lining the outside of the plant pot with the cuttings, it creates humidity in the prospective rootzone and roots things really fast compared to water rooting and using just the substrate and putting in a propagator, i use a propagator too but having an extra layer of very high humidity around the roots and rooting medium speeds things up so much, the cutting roots in times comprable to using rooting hormone (but without the nasty chemicals)

Last edited:

Air layering...rooting clones on the plant.

Ideally you want to prepare a site with nodes then put plugs/coco/moss around the node sites, it's not absolutely necessary (see above lol) but it's advantageous they're likely sites to sprout roots.

It's particularly good for older plants, I can't remember exactly how old but circa 60 days in flower when I cloned it.

Check out Air layering it's a handy to know.

I use air layering balls but some clingfilm/plastic wrapped around the coco, plugs or moss works fine, remember to keep it wet!!

I put a wire around the stem to restrict the flow of sap but not completely cut it off, you can see the strangle mark with basal above it in the pic above.

Ideally you want to prepare a site with nodes then put plugs/coco/moss around the node sites, it's not absolutely necessary (see above lol) but it's advantageous they're likely sites to sprout roots.

It's particularly good for older plants, I can't remember exactly how old but circa 60 days in flower when I cloned it.

Check out Air layering it's a handy to know.

I use air layering balls but some clingfilm/plastic wrapped around the coco, plugs or moss works fine, remember to keep it wet!!

I put a wire around the stem to restrict the flow of sap but not completely cut it off, you can see the strangle mark with basal above it in the pic above.

Last edited:

FilthyDank'Wasteman'Fabul

Active member

Fantastic pictures, textbook quality!Air layering...rooting clones on the plant.

Ideally you want to prepare a site with nodes then put plugs/coco/moss around it.

View attachment 19144013

View attachment 19144011

View attachment 19144009

It's particularly good for older plants, I can't remember exactly how old but circa 60 days in flower when I cloned it.

View attachment 19144012

Check out Air layering it's a handy to know.

headache no sex... a little aspirin andIn the old days they said to use aspirin to reverse sex , I never tried it

Ooh Ee Ooh Ah Ah Ting Tang Walla Walla Bing Bang

seems logical

Last edited:

Thats a great share, post #21 in this thread you could see the prolific roots but the post didnt mention this detailHave found a certain degree of damage to encourage more and faster roots.

Cut through a node to avoid any hollow stem , gently run the pinwheel along the stem four times and rub dry homone powder into the punctures.

View attachment 19144218

Its clear to see how abused the stems were if you look closely, although it needs to be mentioned as im glad you said this!

A little spurring to get things going, seems to be a Professional stitch marking spacer? Been some time since I pulled a stitch.

But yes maceration of some sort seems very helpful, also I have had better results mixing the rooting hormone in water

Using that water for the first drench of the substrate, more testing and results will show if its really a bonus

Also is the excellent rooting that takes place in coco

Were getting a great collective effort here really owe alot of thanks to everyone who has posted here

Hope to see some more success stories

Thanks Mate Dave FilthyDank'Wasteman'Fabul CocoNut 420 foomar its posts like yours that make IC amazing !

Last edited: