Eltitoguay

Well-known member

Sunrise 31 : TRUE, JUSTICE, and REPAIR.

Orwell in Catalonia: joining the POUM militia :

In January 1936, a few days after his arrival in Barcelona, George Orwell made a decision that would mark his subsequent participation in the Spanish Civil War: he decided to join the military, because " at that time and in that environment it seemed the only logical thing to do ."

Orwell travelled to Spain with the firm intention of " killing fascists because someone has to do it ."

These were years of great tension and political radicalisation, where the liberal systems collapsed in the face of the rise of Nazi and fascist authoritarianism. In 1922 Benito Mussolini acceded to the government of Italy with the approval of his king, Victor Emmanuel III, and in 1933 Adolf Hitler did the same in Germany, helped by the conservative right.

In an international climate of tense polarisation, south of the Pyrenees a battle seemed to be taking place between opposing ideals: the II Spanish Republic, which represented democracy and a system of rights and freedoms, or the authoritarianism of the military who rose up against it.

On one side was Joseph Stalin's USSR, on the other the Nazi-fascist axis, and in the middle, fearful of igniting the flame of a new conflict on a global scale, were the liberal powers, especially France and Great Britain, which adopted a neutral policy, thereby condemning the Spanish republican government, in which Soviet influence was decisive.

Orwell arrived in Barcelona on December 26, 1936 with a letter of recommendation from the Independent Labour Party (ILP), a British organization with a Trotskyist orientation that he joined in 1938, after his experience in the Spanish Civil War.

Independent Labour Party - Wikipedia

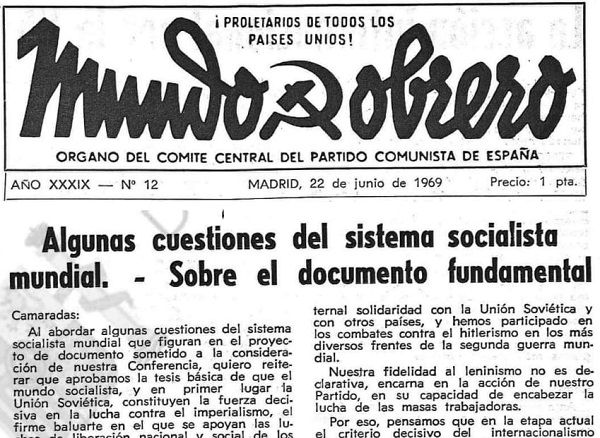

It is therefore not surprising that he chose the militias of the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM), whose political line was similar to that of the ILP, as his space for fighting against Spanish fascism.

Communist Left of Spain - Wikipedia

Workers and Peasants' Bloc - Wikipedia

POUM - Wikipedia

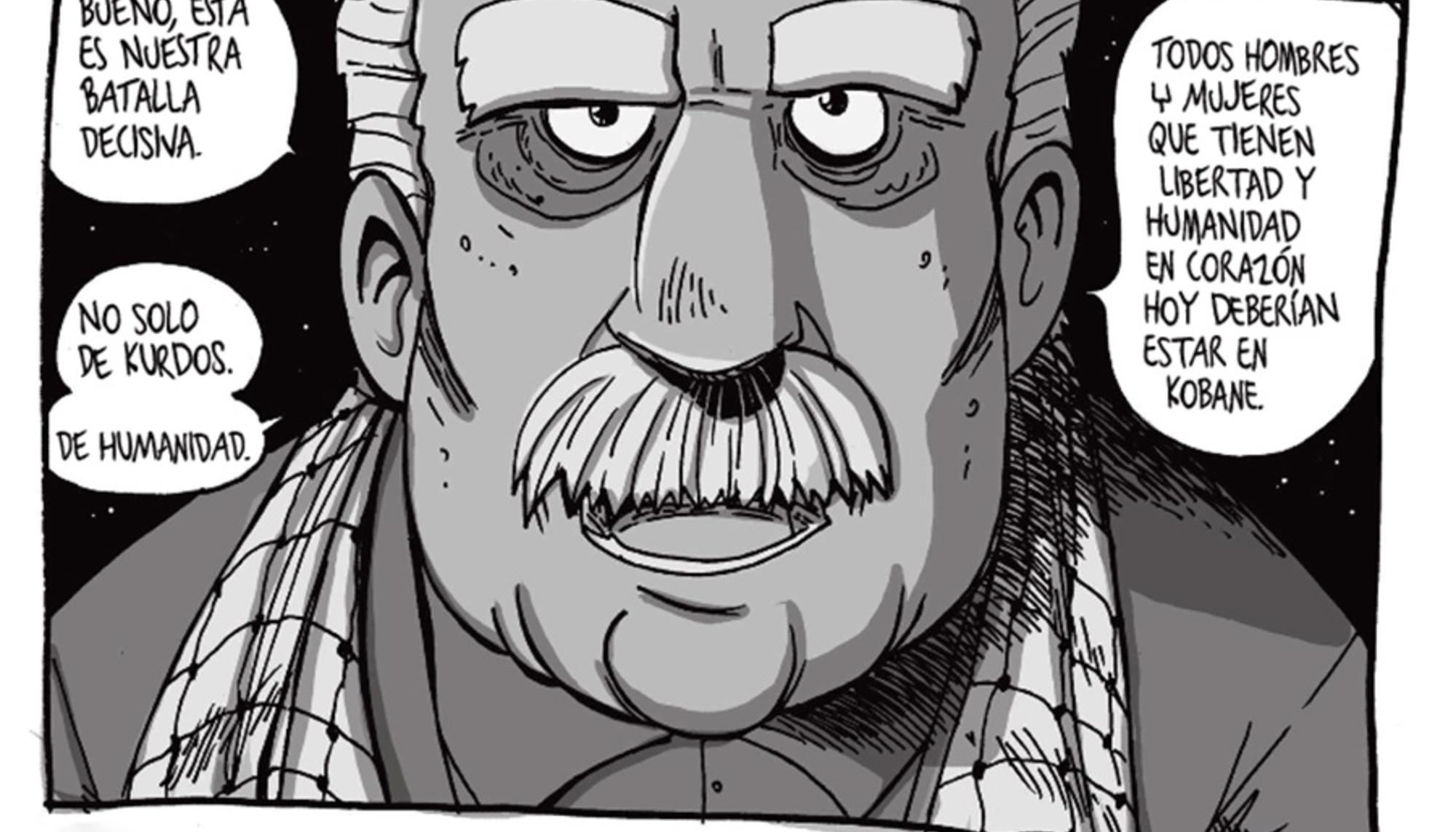

His entry into the militia, although described with a certain romantic air, is presented to us in a crude way, close to the reality that he knew so well.

« How easy it is to make friends in Spain! Within a day or two there were already twenty militiamen who called me by my first name, taught me all sorts of tricks and overwhelmed me with their hospitality. This is not a propaganda book and I do not intend to idealise the POUM militia. The organisation of the militia had serious defects and among the men themselves there was everything, because at that time voluntary isolation was beginning to diminish and many of the best were already dead or at the front. Among us there was always a certain percentage who were totally useless. There were fifteen-year-old boys who had been enlisted by their parents for the ten pesetas a day of wages and for the bread that the militiamen received in abundance and could sneak home. But I challenge anyone to mix with the Spanish workers as I did - although perhaps I should say Catalans, because apart from a few Aragonese and Andalusians I only associated with Catalans - without being impressed by their basic honesty and, above all, their frankness and generosity .

Homage to Catalonia (1938), George Orwell

In early January, Orwell entered the Lenin Barracks, the centre of operations of the POUM militias, where new members were being trained.

Six months had already passed since the outbreak of war and some things, so characteristic of the first moments of the conflict, were beginning to change, including the military participation of women, which was decisive in July 1936, but disdained in January 1937.

Homage to Catalonia (1938), George Orwell

Orwell spent his first days as a militiaman undergoing training.

Soon, the time would come to leave for the front.

Orwell en Cataluña: ingreso en la milicia del POUM

En enero de 1936, a los pocos días de su llegada a Barcelona, George Orwell tomaba una decisión que marcaría su posterior participación en la guerra civil española: decidió ingresar en la milicia, pues «en aquel momento y en aquel ambiente parecía lo único lógico».Orwell viajó a España con la...

www.amanecer31.org

www.amanecer31.org