View attachment 19045147

View attachment 19045151

Small, E. Evolution and Classification of Cannabis sativa (Marijuana, Hemp) in Relation to Human Utilization. Bot. Rev. 81, 189–294 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12229-015-9157-3

View attachment 19045148

View attachment 19045150

View attachment 19045152

View attachment 19045153

View attachment 19045149

Abstract

Cannabis sativa has been employed for thousands of years, primarily as a source of a stem fiber (both the plant and the fiber termed “hemp”) and a resinous intoxicant (the plant and its drug preparations commonly termed “marijuana”). Studies of relationships among various groups of domesticated forms of the species and wild-growing plants have led to conflicting evolutionary interpretations and different classifications, including splitting C. sativa into several alleged species. This review examines the evolving ways Cannabis has been used from ancient times to the present, and how human selection has altered the morphology, chemistry, distribution and ecology of domesticated forms by comparison with related wild plants. Special attention is given to classification, since this has been extremely contentious, and is a key to understanding, exploiting and controlling the plant. Differences that have been used to recognize cultivated groups within Cannabis are the results of disruptive selection for characteristics selected by humans. Wild-growing plants, insofar as has been determined, are either escapes from domesticated forms or the results of thousands of years of widespread genetic exchange with domesticated plants, making it impossible to determine if unaltered primeval or ancestral populations still exist. The conflicting approaches to classifying and naming plants with such interacting domesticated and wild forms are examined. It is recommended that Cannabis sativa be recognized as a single species, within which there is a narcotic subspecies with both domesticated and ruderal varieties, and similarly a non-narcotic subspecies with both domesticated and ruderal varieties. An alternative approach consistent with the international code of nomenclature for cultivated plants is proposed, recognizing six groups: two composed of essentially non-narcotic fiber and oilseed cultivars as well as an additional group composed of their hybrids; and two composed of narcotic strains as well as an additional group composed of their hybrids.

Cannabis Seed Morphology

- Thread starter Thread starter acespicoli

- Start date Start date

-

- Tags Tags

- seed

@Dime interesting observation, find that much of what we think we knew is not what we know now.

drive.google.com

drive.google.com

Micrograph C. sativa (left), C. indica (right)

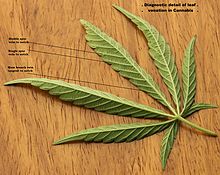

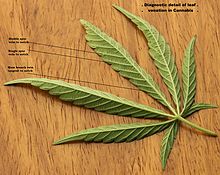

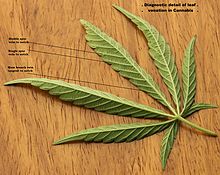

Underside of Cannabis sativa leaf, showing diagnostic venation

The genus Cannabis was formerly placed in the nettle family (Urticaceae) or mulberry family (Moraceae), and later, along with the genus Humulus (hops), in a separate family, the hemp family (Cannabaceae sensu stricto).[48] Recent phylogenetic studies based on cpDNA restriction site analysis and gene sequencing strongly suggest that the Cannabaceae sensu stricto arose from within the former family Celtidaceae, and that the two families should be merged to form a single monophyletic family, the Cannabaceae sensu lato.[49][50]

Various types of Cannabis have been described, and variously classified as species, subspecies, or varieties:[51]

Top of Cannabis plant in vegetative growth stage

Whether the drug and non-drug, cultivated and wild types of Cannabis constitute a single, highly variable species, or the genus is polytypic with more than one species, has been a subject of debate for well over two centuries. This is a contentious issue because there is no universally accepted definition of a species.[57] One widely applied criterion for species recognition is that species are "groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups."[58] Populations that are physiologically capable of interbreeding, but morphologically or genetically divergent and isolated by geography or ecology, are sometimes considered to be separate species.[58] Physiological barriers to reproduction are not known to occur within Cannabis, and plants from widely divergent sources are interfertile.[46] However, physical barriers to gene exchange (such as the Himalayan mountain range) might have enabled Cannabis gene pools to diverge before the onset of human intervention, resulting in speciation.[59] It remains controversial whether sufficient morphological and genetic divergence occurs within the genus as a result of geographical or ecological isolation to justify recognition of more than one species.[60][61][62]

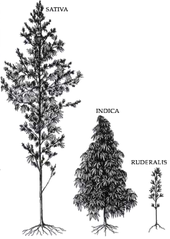

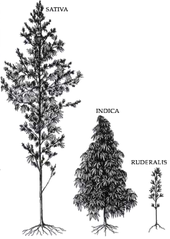

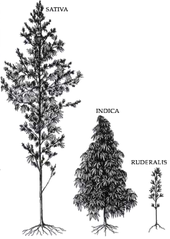

Relative size of varieties of Cannabis

The genus Cannabis was first classified using the "modern" system of taxonomic nomenclature by Carl Linnaeus in 1753, who devised the system still in use for the naming of species.[63] He considered the genus to be monotypic, having just a single species that he named Cannabis sativa L.[a 1] Linnaeus was familiar with European hemp, which was widely cultivated at the time. This classification was supported by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon (in 1807), Lindley (in 1838) and De Candollee (in 1867). These first classifications attempts resulted in a four groups division:[64]

In 1843, William O’Shaughnessy, used "Indian hemp (C. indica)" in a work title. The author claimed that this choice wasn't based in a clear distiction between C. sativa and C. indica, but may have been influenced by the choice to use the term "Indian hemp" (linked to the plant's history in India), hence naming the species as indica.[64]

Additional Cannabis species were proposed in the 19th century, including strains from China and Vietnam (Indo-China) assigned the names Cannabis chinensis Delile, and Cannabis gigantea Delile ex Vilmorin.[66] However, many taxonomists found these putative species difficult to distinguish. In the early 20th century, the single-species concept (monotypic classification) was still widely accepted, except in the Soviet Union where Cannabis continued to be the subject of active taxonomic study. The name Cannabis indica was listed in various Pharmacopoeias, and was widely used to designate Cannabis suitable for the manufacture of medicinal preparations.[67]

Cannabis ruderalis

Cannabis ruderalis

In 1924, Russian botanist D.E. Janichevsky concluded that ruderal Cannabis in central Russia is either a variety of C. sativa or a separate species, and proposed C. sativa L. var. ruderalis Janisch, and Cannabis ruderalis Janisch, as alternative names.[51] In 1929, renowned plant explorer Nikolai Vavilov assigned wild or feral populations of Cannabis in Afghanistan to C. indica Lam. var. kafiristanica Vav., and ruderal populations in Europe to C. sativa L. var. spontanea Vav.[56][66] Vavilov, in 1931, proposed a three species system, independently reinforced by Schultes et al (1975)[68] and Emboden (1974):[69] C. sativa, C. indica and C. ruderalis.[64]

In 1940, Russian botanists Serebriakova and Sizov proposed a complex poly-species classification in which they also recognized C. sativa and C. indica as separate species. Within C. sativa they recognized two subspecies: C. sativa L. subsp. culta Serebr. (consisting of cultivated plants), and C. sativa L. subsp. spontanea (Vav.) Serebr. (consisting of wild or feral plants). Serebriakova and Sizov split the two C. sativa subspecies into 13 varieties, including four distinct groups within subspecies culta. However, they did not divide C. indica into subspecies or varieties.[51][70][71] Zhukovski, in 1950, also proposed a two-species system, but with C. sativa L. and C. ruderalis.[72]

In the 1970s, the taxonomic classification of Cannabis took on added significance in North America. Laws prohibiting Cannabis in the United States and Canada specifically named products of C. sativa as prohibited materials. Enterprising attorneys for the defense in a few drug busts argued that the seized Cannabis material may not have been C. sativa, and was therefore not prohibited by law. Attorneys on both sides recruited botanists to provide expert testimony. Among those testifying for the prosecution was Dr. Ernest Small, while Dr. Richard E. Schultes and others testified for the defense. The botanists engaged in heated debate (outside of court), and both camps impugned the other's integrity.[60][61] The defense attorneys were not often successful in winning their case, because the intent of the law was clear.[73]

Three theories of classification for Cannabis. From left to right, monotypic with three subspecies (A), polytypic consisting of up to three species (B), and single phenotypically diverse species (C).

Three theories of classification for Cannabis. From left to right, monotypic with three subspecies (A), polytypic consisting of up to three species (B), and single phenotypically diverse species (C).

In 1976, Canadian botanist Ernest Small[74] and American taxonomist Arthur Cronquist published a taxonomic revision that recognizes a single species of Cannabis with two subspecies (hemp or drug; based on THC and CBD levels) and two varieties in each (domesticated or wild). The framework is thus:

Professors William Emboden, Loran Anderson, and Harvard botanist Richard E. Schultes and coworkers also conducted taxonomic studies of Cannabis in the 1970s, and concluded that stable morphological differences exist that support recognition of at least three species, C. sativa, C. indica, and C. ruderalis.[76][77][78][79] For Schultes, this was a reversal of his previous interpretation that Cannabis is monotypic, with only a single species.[80] According to Schultes' and Anderson's descriptions, C. sativa is tall and laxly branched with relatively narrow leaflets, C. indica is shorter, conical in shape, and has relatively wide leaflets, and C. ruderalis is short, branchless, and grows wild in Central Asia. This taxonomic interpretation was embraced by Cannabis aficionados who commonly distinguish narrow-leafed "sativa" strains from wide-leafed "indica" strains.[81] McPartland's review finds the Schultes taxonomy inconsistent with prior work (protologs) and partly responsible for the popular usage.[82]

An investigation of genetic, morphological, and chemotaxonomic variation among 157 Cannabis accessions of known geographic origin, including fiber, drug, and feral populations showed cannabinoid variation in Cannabis germplasm. The patterns of cannabinoid variation support recognition of C. sativa and C. indica as separate species, but not C. ruderalis. C. sativa contains fiber and seed landraces, and feral populations, derived from Europe, Central Asia, and Turkey. Narrow-leaflet and wide-leaflet drug accessions, southern and eastern Asian hemp accessions, and feral Himalayan populations were assigned to C. indica.[56] In 2005, a genetic analysis of the same set of accessions led to a three-species classification, recognizing C. sativa, C. indica, and (tentatively) C. ruderalis.[59] Another paper in the series on chemotaxonomic variation in the terpenoid content of the essential oil of Cannabis revealed that several wide-leaflet drug strains in the collection had relatively high levels of certain sesquiterpene alcohols, including guaiol and isomers of eudesmol, that set them apart from the other putative taxa.[87]

A 2020 analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms reports five clusters of cannabis, roughly corresponding to hemps (including folk "Ruderalis") folk "Indica" and folk "Sativa".[88]

Despite advanced analytical techniques, much of the cannabis used recreationally is inaccurately classified. One laboratory at the University of British Columbia found that Jamaican Lamb's Bread, claimed to be 100% sativa, was in fact almost 100% indica (the opposite strain).[89] Legalization of cannabis in Canada (as of 17 October 2018) may help spur private-sector research, especially in terms of diversification of strains. It should also improve classification accuracy for cannabis used recreationally. Legalization coupled with Canadian government (Health Canada) oversight of production and labelling will likely result in more—and more accurate—testing to determine exact strains and content. Furthermore, the rise of craft cannabis growers in Canada should ensure quality, experimentation/research, and diversification of strains among private-sector producers.[90]

1975 v21 No 3 Fall.pdf

drive.google.com

drive.google.com

Micrograph C. sativa (left), C. indica (right)

Taxonomy

Underside of Cannabis sativa leaf, showing diagnostic venation

The genus Cannabis was formerly placed in the nettle family (Urticaceae) or mulberry family (Moraceae), and later, along with the genus Humulus (hops), in a separate family, the hemp family (Cannabaceae sensu stricto).[48] Recent phylogenetic studies based on cpDNA restriction site analysis and gene sequencing strongly suggest that the Cannabaceae sensu stricto arose from within the former family Celtidaceae, and that the two families should be merged to form a single monophyletic family, the Cannabaceae sensu lato.[49][50]

Various types of Cannabis have been described, and variously classified as species, subspecies, or varieties:[51]

- plants cultivated for fiber and seed production, described as low-intoxicant, non-drug, or fiber types.

- plants cultivated for drug production, described as high-intoxicant or drug types.

- escaped, hybridised, or wild forms of either of the above types.

Top of Cannabis plant in vegetative growth stage

Whether the drug and non-drug, cultivated and wild types of Cannabis constitute a single, highly variable species, or the genus is polytypic with more than one species, has been a subject of debate for well over two centuries. This is a contentious issue because there is no universally accepted definition of a species.[57] One widely applied criterion for species recognition is that species are "groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups."[58] Populations that are physiologically capable of interbreeding, but morphologically or genetically divergent and isolated by geography or ecology, are sometimes considered to be separate species.[58] Physiological barriers to reproduction are not known to occur within Cannabis, and plants from widely divergent sources are interfertile.[46] However, physical barriers to gene exchange (such as the Himalayan mountain range) might have enabled Cannabis gene pools to diverge before the onset of human intervention, resulting in speciation.[59] It remains controversial whether sufficient morphological and genetic divergence occurs within the genus as a result of geographical or ecological isolation to justify recognition of more than one species.[60][61][62]

Early classifications

Relative size of varieties of Cannabis

The genus Cannabis was first classified using the "modern" system of taxonomic nomenclature by Carl Linnaeus in 1753, who devised the system still in use for the naming of species.[63] He considered the genus to be monotypic, having just a single species that he named Cannabis sativa L.[a 1] Linnaeus was familiar with European hemp, which was widely cultivated at the time. This classification was supported by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon (in 1807), Lindley (in 1838) and De Candollee (in 1867). These first classifications attempts resulted in a four groups division:[64]

- Kif (southern hemp - psychoactive)

- Vulgaris (intermediate - psychoactive and fiber)

- Pedemontana (northern hemp - fiber)

- Chinensis (northern hemp - fiber)

In 1843, William O’Shaughnessy, used "Indian hemp (C. indica)" in a work title. The author claimed that this choice wasn't based in a clear distiction between C. sativa and C. indica, but may have been influenced by the choice to use the term "Indian hemp" (linked to the plant's history in India), hence naming the species as indica.[64]

Additional Cannabis species were proposed in the 19th century, including strains from China and Vietnam (Indo-China) assigned the names Cannabis chinensis Delile, and Cannabis gigantea Delile ex Vilmorin.[66] However, many taxonomists found these putative species difficult to distinguish. In the early 20th century, the single-species concept (monotypic classification) was still widely accepted, except in the Soviet Union where Cannabis continued to be the subject of active taxonomic study. The name Cannabis indica was listed in various Pharmacopoeias, and was widely used to designate Cannabis suitable for the manufacture of medicinal preparations.[67]

20th century

Further information: Feral cannabis Cannabis ruderalis

Cannabis ruderalisIn 1924, Russian botanist D.E. Janichevsky concluded that ruderal Cannabis in central Russia is either a variety of C. sativa or a separate species, and proposed C. sativa L. var. ruderalis Janisch, and Cannabis ruderalis Janisch, as alternative names.[51] In 1929, renowned plant explorer Nikolai Vavilov assigned wild or feral populations of Cannabis in Afghanistan to C. indica Lam. var. kafiristanica Vav., and ruderal populations in Europe to C. sativa L. var. spontanea Vav.[56][66] Vavilov, in 1931, proposed a three species system, independently reinforced by Schultes et al (1975)[68] and Emboden (1974):[69] C. sativa, C. indica and C. ruderalis.[64]

In 1940, Russian botanists Serebriakova and Sizov proposed a complex poly-species classification in which they also recognized C. sativa and C. indica as separate species. Within C. sativa they recognized two subspecies: C. sativa L. subsp. culta Serebr. (consisting of cultivated plants), and C. sativa L. subsp. spontanea (Vav.) Serebr. (consisting of wild or feral plants). Serebriakova and Sizov split the two C. sativa subspecies into 13 varieties, including four distinct groups within subspecies culta. However, they did not divide C. indica into subspecies or varieties.[51][70][71] Zhukovski, in 1950, also proposed a two-species system, but with C. sativa L. and C. ruderalis.[72]

In the 1970s, the taxonomic classification of Cannabis took on added significance in North America. Laws prohibiting Cannabis in the United States and Canada specifically named products of C. sativa as prohibited materials. Enterprising attorneys for the defense in a few drug busts argued that the seized Cannabis material may not have been C. sativa, and was therefore not prohibited by law. Attorneys on both sides recruited botanists to provide expert testimony. Among those testifying for the prosecution was Dr. Ernest Small, while Dr. Richard E. Schultes and others testified for the defense. The botanists engaged in heated debate (outside of court), and both camps impugned the other's integrity.[60][61] The defense attorneys were not often successful in winning their case, because the intent of the law was clear.[73]

Three theories of classification for Cannabis. From left to right, monotypic with three subspecies (A), polytypic consisting of up to three species (B), and single phenotypically diverse species (C).

Three theories of classification for Cannabis. From left to right, monotypic with three subspecies (A), polytypic consisting of up to three species (B), and single phenotypically diverse species (C).In 1976, Canadian botanist Ernest Small[74] and American taxonomist Arthur Cronquist published a taxonomic revision that recognizes a single species of Cannabis with two subspecies (hemp or drug; based on THC and CBD levels) and two varieties in each (domesticated or wild). The framework is thus:

- C. sativa L. subsp. sativa, presumably selected for traits that enhance fiber or seed production.

- C. sativa L. subsp. sativa var. sativa, domesticated variety.

- C. sativa L. subsp. sativa var. spontanea Vav., wild or escaped variety.

- C. sativa L. subsp. indica (Lam.) Small & Cronq.,[66] primarily selected for drug production.

- C. sativa L. subsp. indica var. indica, domesticated variety.

- C. sativa subsp. indica var. kafiristanica (Vav.) Small & Cronq, wild or escaped variety.

Professors William Emboden, Loran Anderson, and Harvard botanist Richard E. Schultes and coworkers also conducted taxonomic studies of Cannabis in the 1970s, and concluded that stable morphological differences exist that support recognition of at least three species, C. sativa, C. indica, and C. ruderalis.[76][77][78][79] For Schultes, this was a reversal of his previous interpretation that Cannabis is monotypic, with only a single species.[80] According to Schultes' and Anderson's descriptions, C. sativa is tall and laxly branched with relatively narrow leaflets, C. indica is shorter, conical in shape, and has relatively wide leaflets, and C. ruderalis is short, branchless, and grows wild in Central Asia. This taxonomic interpretation was embraced by Cannabis aficionados who commonly distinguish narrow-leafed "sativa" strains from wide-leafed "indica" strains.[81] McPartland's review finds the Schultes taxonomy inconsistent with prior work (protologs) and partly responsible for the popular usage.[82]

Continuing research

Molecular analytical techniques developed in the late 20th century are being applied to questions of taxonomic classification. This has resulted in many reclassifications based on evolutionary systematics. Several studies of random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and other types of genetic markers have been conducted on drug and fiber strains of Cannabis, primarily for plant breeding and forensic purposes.[83][84][28][85][86] Dutch Cannabis researcher E.P.M. de Meijer and coworkers described some of their RAPD studies as showing an "extremely high" degree of genetic polymorphism between and within populations, suggesting a high degree of potential variation for selection, even in heavily selected hemp cultivars.[40] They also commented that these analyses confirm the continuity of the Cannabis gene pool throughout the studied accessions, and provide further confirmation that the genus consists of a single species, although theirs was not a systematic study per se.An investigation of genetic, morphological, and chemotaxonomic variation among 157 Cannabis accessions of known geographic origin, including fiber, drug, and feral populations showed cannabinoid variation in Cannabis germplasm. The patterns of cannabinoid variation support recognition of C. sativa and C. indica as separate species, but not C. ruderalis. C. sativa contains fiber and seed landraces, and feral populations, derived from Europe, Central Asia, and Turkey. Narrow-leaflet and wide-leaflet drug accessions, southern and eastern Asian hemp accessions, and feral Himalayan populations were assigned to C. indica.[56] In 2005, a genetic analysis of the same set of accessions led to a three-species classification, recognizing C. sativa, C. indica, and (tentatively) C. ruderalis.[59] Another paper in the series on chemotaxonomic variation in the terpenoid content of the essential oil of Cannabis revealed that several wide-leaflet drug strains in the collection had relatively high levels of certain sesquiterpene alcohols, including guaiol and isomers of eudesmol, that set them apart from the other putative taxa.[87]

A 2020 analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms reports five clusters of cannabis, roughly corresponding to hemps (including folk "Ruderalis") folk "Indica" and folk "Sativa".[88]

Despite advanced analytical techniques, much of the cannabis used recreationally is inaccurately classified. One laboratory at the University of British Columbia found that Jamaican Lamb's Bread, claimed to be 100% sativa, was in fact almost 100% indica (the opposite strain).[89] Legalization of cannabis in Canada (as of 17 October 2018) may help spur private-sector research, especially in terms of diversification of strains. It should also improve classification accuracy for cannabis used recreationally. Legalization coupled with Canadian government (Health Canada) oversight of production and labelling will likely result in more—and more accurate—testing to determine exact strains and content. Furthermore, the rise of craft cannabis growers in Canada should ensure quality, experimentation/research, and diversification of strains among private-sector producers.[90]

Or vice versa.the best weed I've grown had hollow stem,not saying that.s the way it is,just how it's been for me.@Dime interesting observation, find that much of what we think we knew is not what we know now.

1975 v21 No 3 Fall.pdf

drive.google.com

View attachment 19063902

View attachment 19063900

Micrograph C. sativa (left), C. indica (right)

Taxonomy

Underside of Cannabis sativa leaf, showing diagnostic venation

The genus Cannabis was formerly placed in the nettle family (Urticaceae) or mulberry family (Moraceae), and later, along with the genus Humulus (hops), in a separate family, the hemp family (Cannabaceae sensu stricto).[48] Recent phylogenetic studies based on cpDNA restriction site analysis and gene sequencing strongly suggest that the Cannabaceae sensu stricto arose from within the former family Celtidaceae, and that the two families should be merged to form a single monophyletic family, the Cannabaceae sensu lato.[49][50]

Various types of Cannabis have been described, and variously classified as species, subspecies, or varieties:[51]

Cannabis plants produce a unique family of terpeno-phenolic compounds called cannabinoids, some of which produce the "high" which may be experienced from consuming marijuana. There are 483 identifiable chemical constituents known to exist in the cannabis plant,[52] and at least 85 different cannabinoids have been isolated from the plant.[53] The two cannabinoids usually produced in greatest abundance are cannabidiol (CBD) and/or Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), but only THC is psychoactive.[54] Since the early 1970s, Cannabis plants have been categorized by their chemical phenotype or "chemotype", based on the overall amount of THC produced, and on the ratio of THC to CBD.[55] Although overall cannabinoid production is influenced by environmental factors, the THC/CBD ratio is genetically determined and remains fixed throughout the life of a plant.[40] Non-drug plants produce relatively low levels of THC and high levels of CBD, while drug plants produce high levels of THC and low levels of CBD. When plants of these two chemotypes cross-pollinate, the plants in the first filial (F1) generation have an intermediate chemotype and produce intermediate amounts of CBD and THC. Female plants of this chemotype may produce enough THC to be utilized for drug production.[55][56]

- plants cultivated for fiber and seed production, described as low-intoxicant, non-drug, or fiber types.

- plants cultivated for drug production, described as high-intoxicant or drug types.

- escaped, hybridised, or wild forms of either of the above types.

Top of Cannabis plant in vegetative growth stage

Whether the drug and non-drug, cultivated and wild types of Cannabis constitute a single, highly variable species, or the genus is polytypic with more than one species, has been a subject of debate for well over two centuries. This is a contentious issue because there is no universally accepted definition of a species.[57] One widely applied criterion for species recognition is that species are "groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups."[58] Populations that are physiologically capable of interbreeding, but morphologically or genetically divergent and isolated by geography or ecology, are sometimes considered to be separate species.[58] Physiological barriers to reproduction are not known to occur within Cannabis, and plants from widely divergent sources are interfertile.[46] However, physical barriers to gene exchange (such as the Himalayan mountain range) might have enabled Cannabis gene pools to diverge before the onset of human intervention, resulting in speciation.[59] It remains controversial whether sufficient morphological and genetic divergence occurs within the genus as a result of geographical or ecological isolation to justify recognition of more than one species.[60][61][62]

Early classifications

Relative size of varieties of Cannabis

The genus Cannabis was first classified using the "modern" system of taxonomic nomenclature by Carl Linnaeus in 1753, who devised the system still in use for the naming of species.[63] He considered the genus to be monotypic, having just a single species that he named Cannabis sativa L.[a 1] Linnaeus was familiar with European hemp, which was widely cultivated at the time. This classification was supported by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon (in 1807), Lindley (in 1838) and De Candollee (in 1867). These first classifications attempts resulted in a four groups division:[64]

In 1785, evolutionary biologist Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck published a description of a second species of Cannabis, which he named Cannabis indica Lam.[65] Lamarck based his description of the newly named species on morphological aspects (trichomes, leaf shape) and geographic localization of plant specimens collected in India. He described C. indica as having poorer fiber quality than C. sativa, but greater utility as an inebriant. Also, C. indica was considered smaller, by Lamarck. Also, woodier stems, alternate ramifications of the branches, narrow leaflets, and a villous calyx in the female flowers were carachteristics noted by the botanist.[64]

- Kif (southern hemp - psychoactive)

- Vulgaris (intermediate - psychoactive and fiber)

- Pedemontana (northern hemp - fiber)

- Chinensis (northern hemp - fiber)

In 1843, William O’Shaughnessy, used "Indian hemp (C. indica)" in a work title. The author claimed that this choice wasn't based in a clear distiction between C. sativa and C. indica, but may have been influenced by the choice to use the term "Indian hemp" (linked to the plant's history in India), hence naming the species as indica.[64]

Additional Cannabis species were proposed in the 19th century, including strains from China and Vietnam (Indo-China) assigned the names Cannabis chinensis Delile, and Cannabis gigantea Delile ex Vilmorin.[66] However, many taxonomists found these putative species difficult to distinguish. In the early 20th century, the single-species concept (monotypic classification) was still widely accepted, except in the Soviet Union where Cannabis continued to be the subject of active taxonomic study. The name Cannabis indica was listed in various Pharmacopoeias, and was widely used to designate Cannabis suitable for the manufacture of medicinal preparations.[67]

20th century

Further information: Feral cannabis

Cannabis ruderalis

In 1924, Russian botanist D.E. Janichevsky concluded that ruderal Cannabis in central Russia is either a variety of C. sativa or a separate species, and proposed C. sativa L. var. ruderalis Janisch, and Cannabis ruderalis Janisch, as alternative names.[51] In 1929, renowned plant explorer Nikolai Vavilov assigned wild or feral populations of Cannabis in Afghanistan to C. indica Lam. var. kafiristanica Vav., and ruderal populations in Europe to C. sativa L. var. spontanea Vav.[56][66] Vavilov, in 1931, proposed a three species system, independently reinforced by Schultes et al (1975)[68] and Emboden (1974):[69] C. sativa, C. indica and C. ruderalis.[64]

In 1940, Russian botanists Serebriakova and Sizov proposed a complex poly-species classification in which they also recognized C. sativa and C. indica as separate species. Within C. sativa they recognized two subspecies: C. sativa L. subsp. culta Serebr. (consisting of cultivated plants), and C. sativa L. subsp. spontanea (Vav.) Serebr. (consisting of wild or feral plants). Serebriakova and Sizov split the two C. sativa subspecies into 13 varieties, including four distinct groups within subspecies culta. However, they did not divide C. indica into subspecies or varieties.[51][70][71] Zhukovski, in 1950, also proposed a two-species system, but with C. sativa L. and C. ruderalis.[72]

In the 1970s, the taxonomic classification of Cannabis took on added significance in North America. Laws prohibiting Cannabis in the United States and Canada specifically named products of C. sativa as prohibited materials. Enterprising attorneys for the defense in a few drug busts argued that the seized Cannabis material may not have been C. sativa, and was therefore not prohibited by law. Attorneys on both sides recruited botanists to provide expert testimony. Among those testifying for the prosecution was Dr. Ernest Small, while Dr. Richard E. Schultes and others testified for the defense. The botanists engaged in heated debate (outside of court), and both camps impugned the other's integrity.[60][61] The defense attorneys were not often successful in winning their case, because the intent of the law was clear.[73]

Three theories of classification for Cannabis. From left to right, monotypic with three subspecies (A), polytypic consisting of up to three species (B), and single phenotypically diverse species (C).

In 1976, Canadian botanist Ernest Small[74] and American taxonomist Arthur Cronquist published a taxonomic revision that recognizes a single species of Cannabis with two subspecies (hemp or drug; based on THC and CBD levels) and two varieties in each (domesticated or wild). The framework is thus:

This classification was based on several factors including interfertility, chromosome uniformity, chemotype, and numerical analysis of phenotypic characters.[55][66][75]

- C. sativa L. subsp. sativa, presumably selected for traits that enhance fiber or seed production.

- C. sativa L. subsp. sativa var. sativa, domesticated variety.

- C. sativa L. subsp. sativa var. spontanea Vav., wild or escaped variety.

- C. sativa L. subsp. indica (Lam.) Small & Cronq.,[66] primarily selected for drug production.

- C. sativa L. subsp. indica var. indica, domesticated variety.

- C. sativa subsp. indica var. kafiristanica (Vav.) Small & Cronq, wild or escaped variety.

Professors William Emboden, Loran Anderson, and Harvard botanist Richard E. Schultes and coworkers also conducted taxonomic studies of Cannabis in the 1970s, and concluded that stable morphological differences exist that support recognition of at least three species, C. sativa, C. indica, and C. ruderalis.[76][77][78][79] For Schultes, this was a reversal of his previous interpretation that Cannabis is monotypic, with only a single species.[80] According to Schultes' and Anderson's descriptions, C. sativa is tall and laxly branched with relatively narrow leaflets, C. indica is shorter, conical in shape, and has relatively wide leaflets, and C. ruderalis is short, branchless, and grows wild in Central Asia. This taxonomic interpretation was embraced by Cannabis aficionados who commonly distinguish narrow-leafed "sativa" strains from wide-leafed "indica" strains.[81] McPartland's review finds the Schultes taxonomy inconsistent with prior work (protologs) and partly responsible for the popular usage.[82]

Continuing research

Molecular analytical techniques developed in the late 20th century are being applied to questions of taxonomic classification. This has resulted in many reclassifications based on evolutionary systematics. Several studies of random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and other types of genetic markers have been conducted on drug and fiber strains of Cannabis, primarily for plant breeding and forensic purposes.[83][84][28][85][86] Dutch Cannabis researcher E.P.M. de Meijer and coworkers described some of their RAPD studies as showing an "extremely high" degree of genetic polymorphism between and within populations, suggesting a high degree of potential variation for selection, even in heavily selected hemp cultivars.[40] They also commented that these analyses confirm the continuity of the Cannabis gene pool throughout the studied accessions, and provide further confirmation that the genus consists of a single species, although theirs was not a systematic study per se.

An investigation of genetic, morphological, and chemotaxonomic variation among 157 Cannabis accessions of known geographic origin, including fiber, drug, and feral populations showed cannabinoid variation in Cannabis germplasm. The patterns of cannabinoid variation support recognition of C. sativa and C. indica as separate species, but not C. ruderalis. C. sativa contains fiber and seed landraces, and feral populations, derived from Europe, Central Asia, and Turkey. Narrow-leaflet and wide-leaflet drug accessions, southern and eastern Asian hemp accessions, and feral Himalayan populations were assigned to C. indica.[56] In 2005, a genetic analysis of the same set of accessions led to a three-species classification, recognizing C. sativa, C. indica, and (tentatively) C. ruderalis.[59] Another paper in the series on chemotaxonomic variation in the terpenoid content of the essential oil of Cannabis revealed that several wide-leaflet drug strains in the collection had relatively high levels of certain sesquiterpene alcohols, including guaiol and isomers of eudesmol, that set them apart from the other putative taxa.[87]

A 2020 analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms reports five clusters of cannabis, roughly corresponding to hemps (including folk "Ruderalis") folk "Indica" and folk "Sativa".[88]

Despite advanced analytical techniques, much of the cannabis used recreationally is inaccurately classified. One laboratory at the University of British Columbia found that Jamaican Lamb's Bread, claimed to be 100% sativa, was in fact almost 100% indica (the opposite strain).[89] Legalization of cannabis in Canada (as of 17 October 2018) may help spur private-sector research, especially in terms of diversification of strains. It should also improve classification accuracy for cannabis used recreationally. Legalization coupled with Canadian government (Health Canada) oversight of production and labelling will likely result in more—and more accurate—testing to determine exact strains and content. Furthermore, the rise of craft cannabis growers in Canada should ensure quality, experimentation/research, and diversification of strains among private-sector producers.[90]

Many of the "indica" are woody stem plants

The haze I find that they are "hemp" type plants, maybe not modern hemp type but colonial hemp type

Also of note is the botanical descriptors given by separate botanical experts is biased by their experience

In your study of the plant your likely finding domestic cultivated drug type and feral wild drug types?

All kinds of variation in between ?

sativa indica

Cannabis sativa is an annual herbaceous flowering plant. The species was first classified by Carl Linnaeus in 1753.[1] The specific epithet sativa means 'cultivated'.

en.wikipedia.org

Sativa,[1] sativus,[2] and sativum[3] are Latin botanical adjectives meaning cultivated. It is often associated botanically with plants that promote good health and used to designate certain seed-grown domestic crops.[4]

en.wikipedia.org

Sativa,[1] sativus,[2] and sativum[3] are Latin botanical adjectives meaning cultivated. It is often associated botanically with plants that promote good health and used to designate certain seed-grown domestic crops.[4]

Theres another white paper on dwarf crops it goes into detail of dwarf germplasm and large seed

Good read

Will go on discussing sharing thought on this stuff for hours

Theres a preference I have as well for wispy hollow stem sativa effects, wild cannabis

@Dime always enjoy your posts and perspectives agree whole heartedly

The haze I find that they are "hemp" type plants, maybe not modern hemp type but colonial hemp type

Also of note is the botanical descriptors given by separate botanical experts is biased by their experience

In your study of the plant your likely finding domestic cultivated drug type and feral wild drug types?

All kinds of variation in between ?

sativa indica

Cannabis sativa is an annual herbaceous flowering plant. The species was first classified by Carl Linnaeus in 1753.[1] The specific epithet sativa means 'cultivated'.

Sativum - Wikipedia

Theres another white paper on dwarf crops it goes into detail of dwarf germplasm and large seed

Dwarf germplasm: the key to giant Cannabis hempseed and cannabinoid crops

- April 2018

- Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 65(1)

Good read

Will go on discussing sharing thought on this stuff for hours

Theres a preference I have as well for wispy hollow stem sativa effects, wild cannabis

@Dime always enjoy your posts and perspectives agree whole heartedly

Sorghum - Wikipedia

Interesting when you think about it dwarf Sorghum has been bred from a single plant

in a field you see many dwarf plants, occasionally there are a few tall ones that pop up here and there...

They are both Sorghum right

Indica is classical Greek and Latin for "of India".

Indica - Wikipedia

Sativa,[1] sativus,[2] and sativum[3] are Latin botanical adjectives meaning cultivated. It is often associated botanically with plants that promote good health and used to designate certain seed-grown domestic crops.[4]

Sativum - Wikipedia

PhytoKeys. 2020; 144: 81–112.

Published online 2020 Apr 3. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.144.46700

PMCID: PMC7148385

PMID: 32296283

A classification of endangered high-THC cannabis

(Cannabis sativa subsp. indica) domesticates and their wild relatives

Agree

Yes and indica was named to differentiate between drug and hemp cannabis in adjacent fields so seeds could be seperated. Before prohibition the pharma companies used indian cannabis to make their tinctures and they called it indica as well.

This has obliterated differences between hybridized “Sativa” and “Indica” currently available. “Strains” alleged to represent “Sativa” and “Indica” are usually based on THC/CBD ratios of plants with undocumented hybrid backgrounds (with so-called “Indicas” often delimited simply on possession of more CBD than “Sativas”). The classification presented here circumscribes and names four taxa of Cannabis that represent critically endangered reservoirs of germplasm from which modern cannabinoid strains originated, and which are in urgent need of conservation.

PhytoKeys. 2020; 144: 81–112.

Published online 2020 Apr 3. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.144.46700

_endangered high-THC cannabis.pdf

drive.google.com

drive.google.com

Attachments

Last edited:

A lot of it is unproven,when thc is synthesized it's very unpleasant. I wonder if it gets more credit than it deserves and it's more of a combination in the right amounts of chemicals and terpenes that makes it quality. There are claims of 28+% thc in government weed and I've smoked it and I wouldn't grow it or smoke it again and I suspect what I grow would not hit 20's maybe 1/2, I don't know. I have read claims of 7% thc content in 70's weed that would rock you. Science can't explain everything.

Did alot of terpene research lately past couple years...

Every new report they discover yet another previously unknown terpene and or cannabinoids

Seems like alot of young people are concerned more with high THC levels than they are terpenes.

For me its like fine wine or hops used for beer and experience to be savored.

Maybe a time will come when regional cannabis growers around the world will receive the same respect.

Even coffee or tea best examples are something special to be experienced.

Lebanese hash, Afghan hash, African Malawi cobs, Thai Sticks...

many things id rather hear about on the dispensary shelf's than cookies and cake

Genome Biol Evol. 2021 Aug; 13(8): evab130.

Published online 2021 Jun 8. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evab130

J Cannabis Res. 2021; 3: 7.

Published online 2021 Mar 15. doi: 10.1186/s42238-021-00062-4

PLoS One. 2017; 12(3): e0173911.

Published online 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173911

Different carbon lengths of each terpene and flowering times of synthesis for those compounds...

26 week strains not real popular for commercial growers, reason for weak hybrids of today

Terpenes (/ˈtɜːrpiːn/) are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n ≥ 2. Terpenes are major biosynthetic building blocks. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predominantly by plants, particularly conifers.[1][2][3]

Salvinorin A is the main active psychotropic molecule in Salvia divinorum. Salvinorin A is considered a dissociative hallucinogen.[3][4]

Many more studies out there on the effects of terpenes on the brain and the various receptors

Preserving the best land races in reg format very important, hopefully they are grown wild again

Best >>>

Every new report they discover yet another previously unknown terpene and or cannabinoids

Seems like alot of young people are concerned more with high THC levels than they are terpenes.

For me its like fine wine or hops used for beer and experience to be savored.

Maybe a time will come when regional cannabis growers around the world will receive the same respect.

Even coffee or tea best examples are something special to be experienced.

Lebanese hash, Afghan hash, African Malawi cobs, Thai Sticks...

many things id rather hear about on the dispensary shelf's than cookies and cake

Genome Biol Evol. 2021 Aug; 13(8): evab130.

Published online 2021 Jun 8. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evab130

Origin and Evolution of the Cannabinoid Oxidocyclase Gene Family

If all we care about is the THC or CBD gene thats easy but kinda boring, tasteless weed...J Cannabis Res. 2021; 3: 7.

Published online 2021 Mar 15. doi: 10.1186/s42238-021-00062-4

The biosynthesis of the cannabinoids

PLoS One. 2017; 12(3): e0173911.

Published online 2017 Mar 29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173911

Terpene synthases from Cannabis sativa

Different carbon lengths of each terpene and flowering times of synthesis for those compounds...

26 week strains not real popular for commercial growers, reason for weak hybrids of today

Terpenes (/ˈtɜːrpiːn/) are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n ≥ 2. Terpenes are major biosynthetic building blocks. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predominantly by plants, particularly conifers.[1][2][3]

| Terpenoids | Analogue terpenes | Number of isoprene units | Number of carbon atoms | General formula | Examples[8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemiterpenoids | Isoprene | 1 | 5 | C5H8 | DMAPP, isopentenyl pyrophosphate, isoprenol, isovaleramide, isovaleric acid, HMBPP, prenol |

| Monoterpenoids | Monoterpenes | 2 | 10 | C10H16 | Bornyl acetate, camphor, carvone, citral, citronellal, citronellol, geraniol, eucalyptol, hinokitiol, iridoids, linalool, menthol, thymol |

| Sesquiterpenoids | Sesquiterpenes | 3 | 15 | C15H24 | Farnesol, geosmin, humulone |

| Diterpenoids | Diterpenes | 4 | 20 | C20H32 | Abietic acid, ginkgolides, paclitaxel, retinol, salvinorin A, sclareol, steviol |

| Sesterterpenoids | Sesterterpenes | 5 | 25 | C25H40 | Andrastin A, manoalide |

| Triterpenoids | Triterpenes | 6 | 30 | C30H48 | Amyrin, betulinic acid, limonoids, oleanolic acid, sterols, squalene, ursolic acid |

| Tetraterpenoids | Tetraterpenes | 8 | 40 | C40H64 | Carotenoids |

| Polyterpenoid | Polyterpenes | >8 | >40 | (C5H8)n | Gutta-percha, natural rubber |

Many more studies out there on the effects of terpenes on the brain and the various receptors

Preserving the best land races in reg format very important, hopefully they are grown wild again

Best >>>

Last edited:

..oops..disregard

what happens when you smoke scissor hash

what happens when you smoke scissor hash @mudballs

smoked some haze hash the other day and had to go outside for a walk, im with you!

Verdant Whisperer

Well-known member

100% just got a batch from Mexico and seeds look identical. Interesting how none of the phenotypes are sweet except for the grapefruit phenos have mild sweetness to them. They are my favorite the darker tobacco ones are harsh on the throat and overly stimulating.

It takes time to get used to the overly stimulating ones, wouldn't disregard them entirely100% just got a batch from Mexico and seeds look identical. Interesting how none of the phenotypes are sweet except for the grapefruit phenos have mild sweetness to them. They are my favorite the darker tobacco ones are harsh on the throat and overly stimulating.

Thats cool you got some

Verdant Whisperer

Well-known member

Last edited:

Verdant Whisperer

Well-known member

Your right after smoking on this for a couple of days, its not bad its quiet nice the ones i said where overly stimulating. when i first was smoking i had a lower tolerance from a couple days reduced smoke. the terpenes are soft, I've never smoked purple haze but it reminds of that kinda vibe, take the edge off, its a really nice sativa dominant smoke, the joint now has a mildly sweet citrus and incense taste to it, it has an awareness opening effect, yet without too much focus. sativa body high. i wouldnt consider it a bud you'd smoke to jam out as a musician more of that mexican energy of drinking a corona smoking a joint with a friend while cooking some meats on the grill on a sunny day. its not going to make you stoned or too high, or giggly, theres still a mild seriouseness to the high which reflects mexican energies to me.It takes time to get used to the overly stimulating ones, wouldn't disregard them entirely

Thats cool you got some