Montuno

...como el Son...

El Turuñuelo: the splendor and fall of Tartessos :

The experts are shocked that the building is built with techniques and materials that were thought not to have been used throughout the Western Mediterranean until much later.

The steps are fixed with a kind of lime mortar and crushed granite (the Roman opus caementicium ), a century before the first material of these characteristics appeared.

Barely 10% of its surface has been excavated

For

Javier Ramos

15 February, 2019

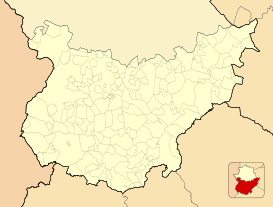

Built on the right bank of the Guadiana River, it is barely separated by seven kilometers from the Tartessian necropolis of Medellín with which, however, it does not have visual contact as the Yelbes mountain range intervenes. It is the tumulus of the Casas del Turuñuelo (in the municipality of Guareña, Badajoz), of great dimensions, which reaches two hectares in size. It is located in a flat valley landscape completely surrounded by irrigated land and is in a good state of conservation. It is about 2,500 years old.

According to Sebastián Celestino, a researcher at the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) who works in the area, Turuñuelo was populated at the end of the Tartessian era, in the 5th century BC. The central core was in the Guadalquivir and Huelva, but after an economic crisis in the 6th century BC there was a large population movement inland. And those people who settled in the Guadiana area built huge buildings like this one and the one in Cancho Roano .

The dimensions of the remains found at the Turuñuelo site are striking: the walls reach up to three meters in height at some points and the whitewash and slate that covered and decorated them are almost intact.

a monumental building

For the moment, one of the 70-square-meter rooms has been completely excavated, which has revealed significant elements, such as a large continuous bench attached to the north wall, as well as an altar in the shape of an extended bull's skin or the presence of a grill and a bronze cauldron, which suggest its connection with cultural activities.To these finds are added the ivory plates of a wooden box decorated with two lions, boats and fish; an outstanding volume of iron from the door fittings; a large number of bronzes belonging to jars, braziers and grills or two braided esparto mats. The room was accessed through a monumental door with a span of 1.70 meters made up of three steps and flanked by two quadrangular pillars that still retain part of their decoration.

But what has most attracted the attention of archaeologists has been the recent discovery of a stairway with ten steps, two meters long by 40 centimeters wide and about 20 centimeters thick, made of granite and covered with slate, carefully joined with something similar to cement. The find is three times larger than the Cancho Roano site and what is surprising is its impressive state of preservation. It points to an unusual two-story building.

surprise architecture

The experts are shocked that the building is built with techniques and materials that were thought not to have been used throughout the western Mediterranean until much later.

The steps are fixed with a kind of lime mortar and crushed granite (the Roman opus caementicium ), a century before the first material of these characteristics appeared.

The building has characteristics of a palace, but also of a great funerary monument.

One of the latest novelties that the excavation has brought about are the bones found of an adult person, probably a man around 1.67 meters tall, which will provide DNA for further investigation. These remains have been discovered in a room other than the patio in which more than fifty horses and other sacrificed animals have appeared, the researchers believe, it is a kind of ritual.

boarded up and set on fire

Most of the constructions of that time in the Guadiana valley were destroyed by their own inhabitants towards the end of the 5th century, or the beginning of the 4th, due to the harassing harassment of the Celtiberian tribes from the north of the peninsula. Turuñuelo was no exception. It was set on fire and then buried under clay taken from the Guadiana River, which has served as a protective framework. Hence its excellent state of preservation.El Turuñuelo is one of the best preserved sites of the Tartessian culture.

Barely 10% of its surface has been excavated, so it is certain that in the future it will bring us new and revealing discoveries that may perhaps change the course of history that we know today.

This spectacular archaeological landmark of our country occupies an important space in the book El Enigma Tartessos

Enigma Tartessos, by Javier Ramos and Javier Martínez Pinna (Editorial Actas) A journey into the past through the mysteries that surround the Tartessian culture and the places that formed part of its territory.

Guareña and its past

Back in the present, the traveler who has fallen in love with this archaeological complex has the opportunity to go to the neighboring town of Guareña to discover the heritage charms that it preserves and makes available to them. This is the homeland of the poet and playwright Luis Chamizo Trigueros, who used the language of his native town in his popular poetry and which has become one of the attributes most recognized by his countrymen.Guareña is one of the best examples of Baja Extremadura. His rich past is easily guessed when the traveler contemplates the magnificent mansions of rich farmers that still remain. The Town Hall stands out , with a classicist design and built entirely in granite masonry in the 18th century. Monumental is also its Renaissance church in which Juan de Herrera himself, the architect of El Escorial , worked .

Where to sleep: Hostal Restaurante Kavanna; 06893 San Pedro de Mérida, (Badajoz); Telephone: 924325022.

-Hostal Fuente de la Magdalena; Spain Square, 20; 06410 Santa Amalia (Badajoz); phone: 605492652.

Where to eat: El Coto; Ctra. Don Benito, S/N; 06470 Guarena, Badajoz; telephone: 924351441.

-Millennium; San Gines Street, 19; 06470 Guarena, Badajoz; phone:924351613.

Last edited: