-

ICMag with help from Landrace Warden and The Vault is running a NEW contest in November! You can check it here. Prizes are seeds & forum premium access. Come join in!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Geography, History and Human Universal Culture:

- Thread starter Montuno

- Start date

Montuno

...como el Son...

Were the predecessors of the Kingdom of Tartessos (Tarsis of the Bible and Phoenician and Greek sources ) the Atlantis of the classical Egyptian and Greek sources ? :

(Both in English)

By James Cameron & NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC:

.

By NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC:

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

(Both in English)

By James Cameron & NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC:

.

By NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC:

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

EL RESURGIR DE LA ATLÁNTIDA

+ LEA LA SINOPSIS DEL PROGRAMA

James Cameron es el productor ejecutivo de este programa de dos horas en el que se investigan, descubren y analizan objetos arqueológicos, fotografías de satélite, manuscritos ocultos a vista de todos, exploraciones submarinas, etc. para tratar de descifrar qué nos cuentan todas estas pistas, y usarlas como trampolín hacia nuevas investigaciones que nos lleven hasta el fondo de la historia de la Atlántida.

Last edited:

Montuno

...como el Son...

Encyclopedic Dictionary of Bible and Theology

2Ch 9:21 because the king's fleet was going to T with

Jon 1:3 to T .. and found a ship leaving for T

Tarshish (Heb. Tarshîsh, perhaps "over the sea" or "breaking"). It is a Phoenician word, derived in turn from Akkadian, which means "foundry", "refinery". This name was given to the localities where the Phoenicians developed mining activities, such as the southeast of Spain, Tunisia and the island of Sardinia. 1. Descendant or descendants of Javan (Gen 10:4; 1Ch 1:7). This Tarsis is generally related to the Tartessus of Spain, known to classical authors, a region located around the central and lower Baetis (the modern Guadalquivir River). This identification is probably correct, because when Jonah went to the port of Joppa and boarded a ship bound for Tarshish, his purpose was to flee to a far country (Jon 1:3), and Tarshish, located in Spain, at the other end of the Mediterranean, could have been that place. According to Isa 60:9 and 66:19 it was a distant land. According to the prophets Jeremiah and Ezekiel, silver (Jer 10:9), iron, tin, and lead (Eze 27:12) came from Tarshish, by which they most likely meant the Tartessus of Spain. However, in 2Ch 9:21 it may refer to a region of Ophir, unless this verse is read in the same way as its parallel text in 1Ki 10:22, in which Tarshish is the name of the fleet of ships of Solomon. Map IV B-1. See Tarshish 2. Bib.: Herodotus iv.152. 2. The expression “ships from Tarshish” has been generally interpreted as referring to a large fleet of ships capable of sailing to Spain. However, it has recently been suggested that it should probably be translated as “refined ore fleet”, This is how the ships that brought the metals from the various refineries around the world to the markets were designated. In some of the OT passages where these ships are mentioned, the Phoenicians collaborated with the Israelites in joint ventures (1Ki 10:22; 2Ch 9:21), or owned or crewed them (Isa 23:1, 14). ; Eze 27:25). Other passages that mention these ships are 1Ki 22:48, Psa 48:7 and Isa 2:16 Bib.: WF Albright, BASOR 83 (1941):21, 22. 3. Benjaminite, son of Bilhan (1Ch 7:10) . 4. Name of one of the 7 notable princes of the Persian Empire at the time of King Ahasuerus (Xerxes; Est 1:14). Since it is applied to him, the name seems Persian, but its etymology is unknown. In some of the OT passages where these ships are mentioned, the Phoenicians collaborated with the Israelites in joint ventures (1Ki 10:22; 2Ch 9:21), or owned or crewed them (Isa 23:1, 14). ; Eze 27:25). Other passages that mention these ships are 1Ki 22:48, Psa 48:7 and Isa 2:16 Bib.: WF Albright, BASOR 83 (1941):21, 22. 3. Benjaminite, son of Bilhan (1Ch 7:10) . 4. Name of one of the 7 notable princes of the Persian Empire at the time of King Ahasuerus (Xerxes; Est 1:14). Since it is applied to him, the name seems Persian, but its etymology is unknown. In some of the OT passages where these ships are mentioned, the Phoenicians collaborated with the Israelites in joint ventures (1Ki 10:22; 2Ch 9:21), or owned or crewed them (Isa 23:1, 14). ; Eze 27:25). Other passages that mention these ships are 1Ki 22:48, Psa 48:7 and Isa 2:16 Bib.: WF Albright, BASOR 83 (1941):21, 22. 3. Benjaminite, son of Bilhan (1Ch 7:10) . 4. Name of one of the 7 notable princes of the Persian Empire at the time of King Ahasuerus (Xerxes; Est 1:14). Since it is applied to him, the name seems Persian, but its etymology is unknown. 16 Bib.: WF Albright, BASOR 83 (1941):21, 22. 3. Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1Ch 7:10). 4. Name of one of the 7 notable princes of the Persian Empire at the time of King Ahasuerus (Xerxes; Est 1:14). Since it is applied to him, the name seems Persian, but its etymology is unknown. 16 Bib.: WF Albright, BASOR 83 (1941):21, 22. 3. Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1Ch 7:10). 4. Name of one of the 7 notable princes of the Persian Empire at the time of King Ahasuerus (Xerxes; Est 1:14). Since it is applied to him, the name seems Persian, but its etymology is unknown.

Source: Evangelical Bible Dictionary

name of a man, of a stone and of a city. 1. Son of Javan, Gn 10, 4. 2. One of the seven princes of Persia and Media. King Ahasuerus especially enjoyed privileges, Est 1, 14. 3. Son of Bilhan, 1 Chr 7, 10. 4. Precious stone that is sometimes translated in the Bible as beryl, Ex 28, 20; 39, 13; Dt 10, 6. Other times it is translated as chrysolite, Ez 1, 16; 10, 9; 28, 13; and as a sapphire, Ct 5, 14. 5. City that is not clearly identified, towards which Jonah embarked, with the purpose of fleeing from the presence of Yahweh, Jon 1, 3. It is assumed that T. was a port in the Mediterranean Sea, distant from Palestine.

Digital Bible Dictionary, Grupo C Service & Design Ltda., Colombia, 2003

Source: Digital Bible Dictionary

1. Son of Javan, great-grandson of Noah (Gen 10:4).

2. A place presumably in the western Mediterranean region, conjectured by many to be identifiable with Tartessos, an ancient city on the Atlantic coast of Spain (Jon 1:3).

3. Fleet of Tarshish seems to refer to large ships of the kind and size used in the Tarshish trade (1Ki 10:22).

4.

A great-grandson of Benjamin (1Ch 7:10).

5. One of the seven princes of Persia and Media who were in the presence of Xerxes, who was Ahasuerus (Est 1:14).

Source: Hispanic World Bible Dictionary

(avid).

Port in the Mediterranean where one of the Magi came from: (Sal 72:10). It is thought that it could be Spain or Tunisia.

Christian Biblical Dictionary

Dr. J. Dominguez

Source: Christian Bible Dictionary

(Beryl, yellow jasper?). Name of people and places of the OT.

1. Second of the sons of †¢Javan (Gen 10:4).

. Name by which a distant region is designated in the Bible, a land from which great wealth was brought, linked in some way with †¢Javán, that is, Greece. The remoteness of this land forced the use of large ships, capable of long voyages, from which the name "ships of T." came for ships with these characteristics (1Ki 10:22; 1Ki 22:48; Ps 48:7 ). But the word was used to refer to foreign lands, in a general sense, which is why it seems somewhat vague to us today. The Phoenicians were the ones who handled most of the trade with those distant lands, for which Tire is called “daughter of T.†, since she depended on that trade for her prosperity (Isa 23:10; Eze 27:12). From there it was brought “silver, iron, tin and lead” (Jer 10:9; Eze 27:12), from which it follows that T. was a Mediterranean country.

Solomon, associated with the Phoenician king †¢Hiram, sent ships to T., which brought †œgold, silver, ivory, monkeys and peacocks† . The time required for these expeditions (three years) indicates the remoteness of the lands (1Ki 10:22; 2Ch 9:21). The term T. is used to designate distant lands that were in the Mediterranean, to the west. Thus, †¢Jonah took a ship at Joppa to go to T. (Jon 1:3). But it is also used to point to lands to the east, since King Jehoshaphat, in association with Ahaziah of Israel, tried to build ships at †¢Ezion-geber †œthat would go to T.† †œThe ships were broken and could not go to T.† (1Ki 22:48; 2Ch 20:35-37).

far away will come the expatriates of Israel, who will return in “ships of T.† to their land (Isa 60:9). God promises to send messengers to the nations, even to distant T., saying, “They will publish my glory among the nations” (Isa 66:19). “The kings of T. and of the coastlands shall bring presents” before the Messiah (Ps 72:10). Most scholars accept that the name of T. possibly comes from Tartesus, a Phoenician colony on the banks of the Guadalquivir, in Spain.

Source: Christian Bible Dictionary

(1)-TARSHIS

1Ki 10:22 the king had .. a fleet of ships from T2Ch 9:21 because the king's fleet was going to T with

Jon 1:3 to T .. and found a ship leaving for T

Tarshish (Heb. Tarshîsh, perhaps "over the sea" or "breaking"). It is a Phoenician word, derived in turn from Akkadian, which means "foundry", "refinery". This name was given to the localities where the Phoenicians developed mining activities, such as the southeast of Spain, Tunisia and the island of Sardinia. 1. Descendant or descendants of Javan (Gen 10:4; 1Ch 1:7). This Tarsis is generally related to the Tartessus of Spain, known to classical authors, a region located around the central and lower Baetis (the modern Guadalquivir River). This identification is probably correct, because when Jonah went to the port of Joppa and boarded a ship bound for Tarshish, his purpose was to flee to a far country (Jon 1:3), and Tarshish, located in Spain, at the other end of the Mediterranean, could have been that place. According to Isa 60:9 and 66:19 it was a distant land. According to the prophets Jeremiah and Ezekiel, silver (Jer 10:9), iron, tin, and lead (Eze 27:12) came from Tarshish, by which they most likely meant the Tartessus of Spain. However, in 2Ch 9:21 it may refer to a region of Ophir, unless this verse is read in the same way as its parallel text in 1Ki 10:22, in which Tarshish is the name of the fleet of ships of Solomon. Map IV B-1. See Tarshish 2. Bib.: Herodotus iv.152. 2. The expression “ships from Tarshish” has been generally interpreted as referring to a large fleet of ships capable of sailing to Spain. However, it has recently been suggested that it should probably be translated as “refined ore fleet”, This is how the ships that brought the metals from the various refineries around the world to the markets were designated. In some of the OT passages where these ships are mentioned, the Phoenicians collaborated with the Israelites in joint ventures (1Ki 10:22; 2Ch 9:21), or owned or crewed them (Isa 23:1, 14). ; Eze 27:25). Other passages that mention these ships are 1Ki 22:48, Psa 48:7 and Isa 2:16 Bib.: WF Albright, BASOR 83 (1941):21, 22. 3. Benjaminite, son of Bilhan (1Ch 7:10) . 4. Name of one of the 7 notable princes of the Persian Empire at the time of King Ahasuerus (Xerxes; Est 1:14). Since it is applied to him, the name seems Persian, but its etymology is unknown. In some of the OT passages where these ships are mentioned, the Phoenicians collaborated with the Israelites in joint ventures (1Ki 10:22; 2Ch 9:21), or owned or crewed them (Isa 23:1, 14). ; Eze 27:25). Other passages that mention these ships are 1Ki 22:48, Psa 48:7 and Isa 2:16 Bib.: WF Albright, BASOR 83 (1941):21, 22. 3. Benjaminite, son of Bilhan (1Ch 7:10) . 4. Name of one of the 7 notable princes of the Persian Empire at the time of King Ahasuerus (Xerxes; Est 1:14). Since it is applied to him, the name seems Persian, but its etymology is unknown. In some of the OT passages where these ships are mentioned, the Phoenicians collaborated with the Israelites in joint ventures (1Ki 10:22; 2Ch 9:21), or owned or crewed them (Isa 23:1, 14). ; Eze 27:25). Other passages that mention these ships are 1Ki 22:48, Psa 48:7 and Isa 2:16 Bib.: WF Albright, BASOR 83 (1941):21, 22. 3. Benjaminite, son of Bilhan (1Ch 7:10) . 4. Name of one of the 7 notable princes of the Persian Empire at the time of King Ahasuerus (Xerxes; Est 1:14). Since it is applied to him, the name seems Persian, but its etymology is unknown. 16 Bib.: WF Albright, BASOR 83 (1941):21, 22. 3. Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1Ch 7:10). 4. Name of one of the 7 notable princes of the Persian Empire at the time of King Ahasuerus (Xerxes; Est 1:14). Since it is applied to him, the name seems Persian, but its etymology is unknown. 16 Bib.: WF Albright, BASOR 83 (1941):21, 22. 3. Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1Ch 7:10). 4. Name of one of the 7 notable princes of the Persian Empire at the time of King Ahasuerus (Xerxes; Est 1:14). Since it is applied to him, the name seems Persian, but its etymology is unknown.

Source: Evangelical Bible Dictionary

name of a man, of a stone and of a city. 1. Son of Javan, Gn 10, 4. 2. One of the seven princes of Persia and Media. King Ahasuerus especially enjoyed privileges, Est 1, 14. 3. Son of Bilhan, 1 Chr 7, 10. 4. Precious stone that is sometimes translated in the Bible as beryl, Ex 28, 20; 39, 13; Dt 10, 6. Other times it is translated as chrysolite, Ez 1, 16; 10, 9; 28, 13; and as a sapphire, Ct 5, 14. 5. City that is not clearly identified, towards which Jonah embarked, with the purpose of fleeing from the presence of Yahweh, Jon 1, 3. It is assumed that T. was a port in the Mediterranean Sea, distant from Palestine.

Digital Bible Dictionary, Grupo C Service & Design Ltda., Colombia, 2003

Source: Digital Bible Dictionary

1. Son of Javan, great-grandson of Noah (Gen 10:4).

2. A place presumably in the western Mediterranean region, conjectured by many to be identifiable with Tartessos, an ancient city on the Atlantic coast of Spain (Jon 1:3).

3. Fleet of Tarshish seems to refer to large ships of the kind and size used in the Tarshish trade (1Ki 10:22).

4.

A great-grandson of Benjamin (1Ch 7:10).

5. One of the seven princes of Persia and Media who were in the presence of Xerxes, who was Ahasuerus (Est 1:14).

Source: Hispanic World Bible Dictionary

(avid).

Port in the Mediterranean where one of the Magi came from: (Sal 72:10). It is thought that it could be Spain or Tunisia.

Christian Biblical Dictionary

Dr. J. Dominguez

Genesis 1 | KJV Bible | YouVersion

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the S...

bible.com

(Beryl, yellow jasper?). Name of people and places of the OT.

1. Second of the sons of †¢Javan (Gen 10:4).

. Name by which a distant region is designated in the Bible, a land from which great wealth was brought, linked in some way with †¢Javán, that is, Greece. The remoteness of this land forced the use of large ships, capable of long voyages, from which the name "ships of T." came for ships with these characteristics (1Ki 10:22; 1Ki 22:48; Ps 48:7 ). But the word was used to refer to foreign lands, in a general sense, which is why it seems somewhat vague to us today. The Phoenicians were the ones who handled most of the trade with those distant lands, for which Tire is called “daughter of T.†, since she depended on that trade for her prosperity (Isa 23:10; Eze 27:12). From there it was brought “silver, iron, tin and lead” (Jer 10:9; Eze 27:12), from which it follows that T. was a Mediterranean country.

Solomon, associated with the Phoenician king †¢Hiram, sent ships to T., which brought †œgold, silver, ivory, monkeys and peacocks† . The time required for these expeditions (three years) indicates the remoteness of the lands (1Ki 10:22; 2Ch 9:21). The term T. is used to designate distant lands that were in the Mediterranean, to the west. Thus, †¢Jonah took a ship at Joppa to go to T. (Jon 1:3). But it is also used to point to lands to the east, since King Jehoshaphat, in association with Ahaziah of Israel, tried to build ships at †¢Ezion-geber †œthat would go to T.† †œThe ships were broken and could not go to T.† (1Ki 22:48; 2Ch 20:35-37).

far away will come the expatriates of Israel, who will return in “ships of T.† to their land (Isa 60:9). God promises to send messengers to the nations, even to distant T., saying, “They will publish my glory among the nations” (Isa 66:19). “The kings of T. and of the coastlands shall bring presents” before the Messiah (Ps 72:10). Most scholars accept that the name of T. possibly comes from Tartesus, a Phoenician colony on the banks of the Guadalquivir, in Spain.

Source: Christian Bible Dictionary

Last edited:

Montuno

...como el Son...

Encyclopedic Dictionary of Bible and Theology

vet, Phoenician term derived from Akkadian; pos. "refinery". (a) People sprung from Javan (Gen. 10:4) and its territory. Jonah (Jon. 1:3) embarked from Joppa to reach Tarshish, at the point furthest from Nineveh, and therefore in the west (cf. Is. 66:19). Silver beaten into sheets and plates (Jer. 10:9), iron, tin, lead (Ex. 27:12) were imported from Tarshish. Plausible identification: Tartessos, in southern Spain, not far from Gibraltar (Herodotus 4:152). The Phoenicians, attracted by the mining wealth of the region, founded a colony there. The term "ships of Tarshish" originally designated the ships that made the journey between this place and distant countries. Later the same expression was used to designate ships of greater tonnage, whatever their destination (Ps. 48:7; Is. 2:16; 23:1, 14; 60:9; Ez. 27:25). Jehoshaphat built ships of this class to send to Ophir, but they broke up in the roadstead of Ezion-geber (1 a. 22:49). The expression “ships from Tarshish” has been interpreted as “ships going to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 9:21; cf. 1 Kgs. 10:22) or “ships destined to go to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 20: 36). However, it is possible that the original meaning of the term “Tarshish”, applied to these ships, was “refinery ships”, the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarsis” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14). but they broke up at Ezion-geber roadstead (1 a. 22:49). The expression “ships from Tarshish” has been interpreted as “ships going to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 9:21; cf. 1 Kgs. 10:22) or “ships destined to go to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 20: 36). However, it is possible that the original meaning of the term “Tarshish”, applied to these ships, was “refinery ships”, the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarshish” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14). but they broke up at Ezion-geber roadstead (1 a. 22:49). The expression “ships from Tarshish” has been interpreted as “ships going to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 9:21; cf. 1 Kgs. 10:22) or “ships destined to go to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 20: 36). However, it is possible that the original meaning of the term “Tarshish”, applied to these ships, was “refinery ships”, the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarshish” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14). The expression “ships from Tarshish” has been interpreted as “ships going to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 9:21; cf. 1 Kgs. 10:22) or “ships destined to go to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 20: 36). However, it is possible that the original meaning of the term “Tarshish”, applied to these ships, was “refinery ships”, the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarshish” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14). The expression “ships from Tarshish” has been interpreted as “ships going to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 9:21; cf. 1 Kgs. 10:22) or “ships destined to go to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 20: 36). However, it is possible that the original meaning of the term “Tarshish”, applied to these ships, was “refinery ships”, the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarshish” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14). applied to these ships, it has been "refinery ships", the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarshish” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14). applied to these ships, it has been "refinery ships", the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarshish” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14).

Source: New Illustrated Bible Dictionary

Greek city that traded with Tire (Gen 10.4 Jon. 1.3 and 4.2); Ez. 27.12). The location is very uncertain and its attributions vary from those who place it in "Tartesos" of the distant Betica of Iberia, or perhaps in Carthage, to those who placed it in the Black Sea or perhaps in Sicily.

The ships of Tarshish (1. Kings 10.22) are perhaps identified with the ships of Tire and Sidon, which from ancient times sailed in the Mediterranean in search of new products from distant lands.

Pedro Chico González, Dictionary of Catechesis and Religious Pedagogy, Editorial Bruño, Lima, Peru 2006

Source: Dictionary of Catechesis and Religious Pedagogy

(2)-TARSHIS

vet, Phoenician term derived from Akkadian; pos. "refinery". (a) People sprung from Javan (Gen. 10:4) and its territory. Jonah (Jon. 1:3) embarked from Joppa to reach Tarshish, at the point furthest from Nineveh, and therefore in the west (cf. Is. 66:19). Silver beaten into sheets and plates (Jer. 10:9), iron, tin, lead (Ex. 27:12) were imported from Tarshish. Plausible identification: Tartessos, in southern Spain, not far from Gibraltar (Herodotus 4:152). The Phoenicians, attracted by the mining wealth of the region, founded a colony there. The term "ships of Tarshish" originally designated the ships that made the journey between this place and distant countries. Later the same expression was used to designate ships of greater tonnage, whatever their destination (Ps. 48:7; Is. 2:16; 23:1, 14; 60:9; Ez. 27:25). Jehoshaphat built ships of this class to send to Ophir, but they broke up in the roadstead of Ezion-geber (1 a. 22:49). The expression “ships from Tarshish” has been interpreted as “ships going to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 9:21; cf. 1 Kgs. 10:22) or “ships destined to go to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 20: 36). However, it is possible that the original meaning of the term “Tarshish”, applied to these ships, was “refinery ships”, the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarsis” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14). but they broke up at Ezion-geber roadstead (1 a. 22:49). The expression “ships from Tarshish” has been interpreted as “ships going to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 9:21; cf. 1 Kgs. 10:22) or “ships destined to go to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 20: 36). However, it is possible that the original meaning of the term “Tarshish”, applied to these ships, was “refinery ships”, the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarshish” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14). but they broke up at Ezion-geber roadstead (1 a. 22:49). The expression “ships from Tarshish” has been interpreted as “ships going to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 9:21; cf. 1 Kgs. 10:22) or “ships destined to go to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 20: 36). However, it is possible that the original meaning of the term “Tarshish”, applied to these ships, was “refinery ships”, the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarshish” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14). The expression “ships from Tarshish” has been interpreted as “ships going to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 9:21; cf. 1 Kgs. 10:22) or “ships destined to go to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 20: 36). However, it is possible that the original meaning of the term “Tarshish”, applied to these ships, was “refinery ships”, the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarshish” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14). The expression “ships from Tarshish” has been interpreted as “ships going to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 9:21; cf. 1 Kgs. 10:22) or “ships destined to go to Tarshish” (2 Chr. 20: 36). However, it is possible that the original meaning of the term “Tarshish”, applied to these ships, was “refinery ships”, the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarshish” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14). applied to these ships, it has been "refinery ships", the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarshish” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14). applied to these ships, it has been "refinery ships", the name of similar ships that communicated the mines and refineries of Sardinia and Phoenicia. Later they maintained communication with the refineries in southern Spain. A Phoenician inscription from the 9th century BC discovered in Nora, in Sardinia, speaks of a “tarshish” (or refinery) on this island. (b) Benjamite, son of Bilhan (1 Chron. 7:10). (c) One of the seven princes of Persia (Esther 1:14).

Source: New Illustrated Bible Dictionary

Greek city that traded with Tire (Gen 10.4 Jon. 1.3 and 4.2); Ez. 27.12). The location is very uncertain and its attributions vary from those who place it in "Tartesos" of the distant Betica of Iberia, or perhaps in Carthage, to those who placed it in the Black Sea or perhaps in Sicily.

The ships of Tarshish (1. Kings 10.22) are perhaps identified with the ships of Tire and Sidon, which from ancient times sailed in the Mediterranean in search of new products from distant lands.

Pedro Chico González, Dictionary of Catechesis and Religious Pedagogy, Editorial Bruño, Lima, Peru 2006

Source: Dictionary of Catechesis and Religious Pedagogy

Last edited:

Cuddles

Well-known member

are you referring to paleo?Great stuff! One of my favourite topics - I've been eating caveman style for the past 12 years - does wonders for you!

Montuno

...como el Son...

Encyclopedic Dictionary of Bible and Theology

(from a root meaning: †œto shatter† ).

1. One of the four sons born to Javan after the Flood. (Ge 10: 4; 1Ch 1: 7) He He is included among the 70 heads of families from whom † the nations † were scattered over the earth. (Ge 10:32) As with the other sons of Javan, the name Tarshish was eventually applied to a people and a region.

2. Descendant of Benjamin and son of Bilhan. (1Ch 7:6, 10)

3. One of the seven princes and advisers to King Ahasuerus who considered the case of the rebellious Queen Vashti. (Esther 1:12-15.)

4. Region initially populated by the descendants of Tarshish, son of Javan and grandson of Japheth. There is some indication of the direction in which the descendants of Tarshish migrated during the centuries after the Flood.

The prophet Jonah (c. 844 BCE), commissioned by Jehovah to go to Nineveh, Assyria, attempted to evade his assignment by going to Joppa (modern Tel Aviv-Yafo), a Mediterranean seaport, where he purchased passage to † "a ship going to Tarshish." (Jon 1:1-3; 4:2) Thus, it is obvious that Tarshish had to be in or adjacent to the Mediterranean and away from Nineveh. Besides, it must be easier to get to Tarshish by sea than by land. At Ezekiel 27:25, 26 the expression “the heart of the high sea” is used in connection with “the ships of Tarshish.” (Compare Ps 48:7; Jon 2:3.)

An inscription of the Assyrian emperor Esar-haddon (7th century BCE) boasts of his victories over Tire and Egypt, stating that all the kings of the islands from Cyprus “until Tarsisi” paid tribute to him. (Ancient Near Eastern Texts, ed. JB Pritchard, 1974, p. 290.) Since Cyprus is in the eastern part of the Mediterranean, it can be deduced from this reference that Tarshish was in the western part of that sea, so some scholars they identify it with the island of Sardinia.

Most Possible identification with Spain:

Most scholars associate Tarshish with Spain, based on ancient references to a place or region in Spain that Greek and Roman writers called Tartessos. Although the Greek geographer Strabo (1st century BCE) located a city called Tartessos in the region of the Guadalquivir river in Andalusia (Geografía, 3, II, 11), it seems that Tartessos applies generally to all of S of the Iberian Peninsula.

Numerous reference works assume that the Phoenicians colonized the Spanish coasts, and refer to Tartessos as one of their colonies. However, there does not seem to be enough evidence to support this theory. Therefore, the Encyclopædia Britannica (1959, vol. 21, p. 114) says: “Neither the Phoenicians nor the Carthaginians left a permanent mark on that land. However, the Greeks exercised a profound influence on it. Ships from Tire and Sidon may have traded across the strait and into Cadiz at least as early as the ninth century BC. from JC; however, modern archaeology, which has found and excavated Greek, Iberian and Roman cities, has not brought to light a single Phoenician settlement, nor have Phoenician remains more important than a few trinkets, jewels and other barter items been found. comes off, hence, that, with the possible exception of Cadiz, the Phoenicians did not build cities, but simple posts in which to trade and where their ships could call† . History also shows that when the Phoenicians and the Greeks began to trade in Spain, the place was already populated and the natives brought the silver, iron, tin and lead that the merchants were looking for.

Therefore, there seems to be good reason to believe that the descendants of Javan (the Ionians) along the Tarshish line reached the Iberian Peninsula, where they constituted the most prominent ethnic group. This possible location of Tarshish also harmonizes nicely with the other Biblical references to this place.

Business relations with Solomon. Phoenician trade with Tarshish is clearly corroborated by the record from the time of King Solomon (some thirteen centuries after the Flood), when the nation of Israel also began to engage in maritime trade. Solomon had a fleet of ships in the Red Sea area, some of whose crews were skilled sailors provided by the Phoenician King Hiram of Tyre, and he was especially engaged in trade with the gold-rich land of Ophir. (1Ki 9:26-28) Reference is then made to “a fleet of ships from Tarshish” that Solomon had in the sea “along with the fleet of ships from Hiram,” and these ships are said to have made voyages every three years to import gold, silver, ivory, monkeys and peacocks. (1 Kings 10:22. ) It is believed that the expression †œships from Tarshish† over time represented a type of ship, as a certain lexicon says: †œLarge ships, suitable for high-seas navigation, suitable for making the journey to Tarshish† . (Brown, Driver, and Briggs, A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament, 1980, p. 1077.) Similarly, the English name Indiamen was originally applied to large British ships engaged in trade with India, but over time the term was applied to all ships of that type regardless of their origin or destination. Thus, 1 Kings 22:48 shows that King Jehoshaphat (c. 936-911 BCE) “made ships from Tarshish to go to Ophir for gold.” suitable for making the journey to Tarshish† . (Brown, Driver, and Briggs, A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament, 1980, p. 1077.) Similarly, the English name Indiamen was originally applied to large British ships engaged in trade with India, but over time the term was applied to all ships of that type regardless of their origin or destination. Thus, 1 Kings 22:48 shows that King Jehoshaphat (c. 936-911 BCE) “made ships from Tarshish to go to Ophir for gold.” suitable for making the journey to Tarshish† . (Brown, Driver, and Briggs, A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament, 1980, p. 1077.) Similarly, the English name Indiamen was originally applied to large British ships engaged in trade with India, but over time the term was applied to all ships of that type regardless of their origin or destination. Thus, 1 Kings 22:48 shows that King Jehoshaphat (c. 936-911 BCE) “made ships from Tarshish to go to Ophir for gold.” but over time the term was applied to all ships of that type regardless of their origin or destination. Thus, 1 Kings 22:48 shows that King Jehoshaphat (c. 936-911 BCE) “made ships from Tarshish to go to Ophir for gold.” but over time the term was applied to all ships of that type regardless of their origin or destination. Thus, 1 Kings 22:48 shows that King Jehoshaphat (c. 936-911 BCE) “made ships from Tarshish to go to Ophir for gold.”

However, the Chronicles account specifies that the ships Solomon used for the triennial voyages “went to Tarshish” (2Ch 9:21); furthermore, he comments that Jehoshaphat's ships were designed to "go to Tarshish", but "they broke up, and did not retain strength to go to Tarshish". (2Ch 20:36, 37) These texts indicate that Ophir was not the only port of call for the Israelite “ships of Tarshish,” but that they also sailed Mediterranean waters. Naturally, this poses a problem, as the launching site for at least some of these ships is shown to have been Ezion-geber in the Gulf of `Aqaba. (1Ki 9:26) For ships to reach the Mediterranean Sea, they had to traverse a canal from the Red Sea to the Nile River and then to the Mediterranean, or circumnavigate the African continent.

In the prophecy. It seems that Tarshish was an important market for the commercial city of Tyre, and perhaps the one that provided the greatest wealth for part of its history. Since ancient times, Spain has had mines to exploit its rich deposits of silver, iron, tin and other metals. (Compare Jer 10:9; Eze 27:3, 12.) Thus, Isaiah's formal prophetic statement regarding the fall of Tire says that the ships of Tarshish would †˜howl†™ when they reached Kitim (Cyprus, perhaps their last stop on their way E.) and received news that the prosperous port of Tire had been †˜forcibly despoiled†™. (Isaiah 23:1, 10, 14)

Other prophecies foretell that God would send some of his people to Tarshish to proclaim his glory there (Isa 66:19) and that “ships from Tarshish” would bring the children of Zion from afar. (Isa 60:9) The “kings of Tarshish and of the islands” are said to have to pay tribute to the one Jehovah appoints as king. (Ps 72:10) On the other hand, at Ezekiel 38:13 it is said that the “merchants of Tarshish,” along with other trading peoples, would express selfish interest in Gog of Magog’s proposed plunder of those whom Jehovah had gathered. Since the ships of Tarshish are included among other symbols of vainglory, haughtiness, and haughtiness, they have to be lowered, and Jehovah alone is to be exalted in the “day that belongs to Jehovah of armies.” (Isaiah 2:11-16.)

Source: Dictionary of the Bible

(3)-TARSHIS

(from a root meaning: †œto shatter† ).

1. One of the four sons born to Javan after the Flood. (Ge 10: 4; 1Ch 1: 7) He He is included among the 70 heads of families from whom † the nations † were scattered over the earth. (Ge 10:32) As with the other sons of Javan, the name Tarshish was eventually applied to a people and a region.

2. Descendant of Benjamin and son of Bilhan. (1Ch 7:6, 10)

3. One of the seven princes and advisers to King Ahasuerus who considered the case of the rebellious Queen Vashti. (Esther 1:12-15.)

4. Region initially populated by the descendants of Tarshish, son of Javan and grandson of Japheth. There is some indication of the direction in which the descendants of Tarshish migrated during the centuries after the Flood.

The prophet Jonah (c. 844 BCE), commissioned by Jehovah to go to Nineveh, Assyria, attempted to evade his assignment by going to Joppa (modern Tel Aviv-Yafo), a Mediterranean seaport, where he purchased passage to † "a ship going to Tarshish." (Jon 1:1-3; 4:2) Thus, it is obvious that Tarshish had to be in or adjacent to the Mediterranean and away from Nineveh. Besides, it must be easier to get to Tarshish by sea than by land. At Ezekiel 27:25, 26 the expression “the heart of the high sea” is used in connection with “the ships of Tarshish.” (Compare Ps 48:7; Jon 2:3.)

An inscription of the Assyrian emperor Esar-haddon (7th century BCE) boasts of his victories over Tire and Egypt, stating that all the kings of the islands from Cyprus “until Tarsisi” paid tribute to him. (Ancient Near Eastern Texts, ed. JB Pritchard, 1974, p. 290.) Since Cyprus is in the eastern part of the Mediterranean, it can be deduced from this reference that Tarshish was in the western part of that sea, so some scholars they identify it with the island of Sardinia.

Most Possible identification with Spain:

Most scholars associate Tarshish with Spain, based on ancient references to a place or region in Spain that Greek and Roman writers called Tartessos. Although the Greek geographer Strabo (1st century BCE) located a city called Tartessos in the region of the Guadalquivir river in Andalusia (Geografía, 3, II, 11), it seems that Tartessos applies generally to all of S of the Iberian Peninsula.

Numerous reference works assume that the Phoenicians colonized the Spanish coasts, and refer to Tartessos as one of their colonies. However, there does not seem to be enough evidence to support this theory. Therefore, the Encyclopædia Britannica (1959, vol. 21, p. 114) says: “Neither the Phoenicians nor the Carthaginians left a permanent mark on that land. However, the Greeks exercised a profound influence on it. Ships from Tire and Sidon may have traded across the strait and into Cadiz at least as early as the ninth century BC. from JC; however, modern archaeology, which has found and excavated Greek, Iberian and Roman cities, has not brought to light a single Phoenician settlement, nor have Phoenician remains more important than a few trinkets, jewels and other barter items been found. comes off, hence, that, with the possible exception of Cadiz, the Phoenicians did not build cities, but simple posts in which to trade and where their ships could call† . History also shows that when the Phoenicians and the Greeks began to trade in Spain, the place was already populated and the natives brought the silver, iron, tin and lead that the merchants were looking for.

Therefore, there seems to be good reason to believe that the descendants of Javan (the Ionians) along the Tarshish line reached the Iberian Peninsula, where they constituted the most prominent ethnic group. This possible location of Tarshish also harmonizes nicely with the other Biblical references to this place.

Business relations with Solomon. Phoenician trade with Tarshish is clearly corroborated by the record from the time of King Solomon (some thirteen centuries after the Flood), when the nation of Israel also began to engage in maritime trade. Solomon had a fleet of ships in the Red Sea area, some of whose crews were skilled sailors provided by the Phoenician King Hiram of Tyre, and he was especially engaged in trade with the gold-rich land of Ophir. (1Ki 9:26-28) Reference is then made to “a fleet of ships from Tarshish” that Solomon had in the sea “along with the fleet of ships from Hiram,” and these ships are said to have made voyages every three years to import gold, silver, ivory, monkeys and peacocks. (1 Kings 10:22. ) It is believed that the expression †œships from Tarshish† over time represented a type of ship, as a certain lexicon says: †œLarge ships, suitable for high-seas navigation, suitable for making the journey to Tarshish† . (Brown, Driver, and Briggs, A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament, 1980, p. 1077.) Similarly, the English name Indiamen was originally applied to large British ships engaged in trade with India, but over time the term was applied to all ships of that type regardless of their origin or destination. Thus, 1 Kings 22:48 shows that King Jehoshaphat (c. 936-911 BCE) “made ships from Tarshish to go to Ophir for gold.” suitable for making the journey to Tarshish† . (Brown, Driver, and Briggs, A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament, 1980, p. 1077.) Similarly, the English name Indiamen was originally applied to large British ships engaged in trade with India, but over time the term was applied to all ships of that type regardless of their origin or destination. Thus, 1 Kings 22:48 shows that King Jehoshaphat (c. 936-911 BCE) “made ships from Tarshish to go to Ophir for gold.” suitable for making the journey to Tarshish† . (Brown, Driver, and Briggs, A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament, 1980, p. 1077.) Similarly, the English name Indiamen was originally applied to large British ships engaged in trade with India, but over time the term was applied to all ships of that type regardless of their origin or destination. Thus, 1 Kings 22:48 shows that King Jehoshaphat (c. 936-911 BCE) “made ships from Tarshish to go to Ophir for gold.” but over time the term was applied to all ships of that type regardless of their origin or destination. Thus, 1 Kings 22:48 shows that King Jehoshaphat (c. 936-911 BCE) “made ships from Tarshish to go to Ophir for gold.” but over time the term was applied to all ships of that type regardless of their origin or destination. Thus, 1 Kings 22:48 shows that King Jehoshaphat (c. 936-911 BCE) “made ships from Tarshish to go to Ophir for gold.”

However, the Chronicles account specifies that the ships Solomon used for the triennial voyages “went to Tarshish” (2Ch 9:21); furthermore, he comments that Jehoshaphat's ships were designed to "go to Tarshish", but "they broke up, and did not retain strength to go to Tarshish". (2Ch 20:36, 37) These texts indicate that Ophir was not the only port of call for the Israelite “ships of Tarshish,” but that they also sailed Mediterranean waters. Naturally, this poses a problem, as the launching site for at least some of these ships is shown to have been Ezion-geber in the Gulf of `Aqaba. (1Ki 9:26) For ships to reach the Mediterranean Sea, they had to traverse a canal from the Red Sea to the Nile River and then to the Mediterranean, or circumnavigate the African continent.

In the prophecy. It seems that Tarshish was an important market for the commercial city of Tyre, and perhaps the one that provided the greatest wealth for part of its history. Since ancient times, Spain has had mines to exploit its rich deposits of silver, iron, tin and other metals. (Compare Jer 10:9; Eze 27:3, 12.) Thus, Isaiah's formal prophetic statement regarding the fall of Tire says that the ships of Tarshish would †˜howl†™ when they reached Kitim (Cyprus, perhaps their last stop on their way E.) and received news that the prosperous port of Tire had been †˜forcibly despoiled†™. (Isaiah 23:1, 10, 14)

Other prophecies foretell that God would send some of his people to Tarshish to proclaim his glory there (Isa 66:19) and that “ships from Tarshish” would bring the children of Zion from afar. (Isa 60:9) The “kings of Tarshish and of the islands” are said to have to pay tribute to the one Jehovah appoints as king. (Ps 72:10) On the other hand, at Ezekiel 38:13 it is said that the “merchants of Tarshish,” along with other trading peoples, would express selfish interest in Gog of Magog’s proposed plunder of those whom Jehovah had gathered. Since the ships of Tarshish are included among other symbols of vainglory, haughtiness, and haughtiness, they have to be lowered, and Jehovah alone is to be exalted in the “day that belongs to Jehovah of armies.” (Isaiah 2:11-16.)

Source: Dictionary of the Bible

Montuno

...como el Son...

Encyclopedic Dictionary of Bible and Theology

1. Grandson of Benjamin, son of Bilhan (1 Chr. 7.10) 2. One of the seven prominent princes of Ahasuerus, ruler of Persia (Est. 1.14).

3. Son of Javan, grandson of Noah (Gen. 10.4; 1 Chr. 1.7). The name Tarshish ( taršı̂š ) refers both to the descendants and to the land.

Several of the OT references relate to ships and suggest that Tarshish was on the seashore. So Jonah embarked on a ship that left for Tarshish (Jon. 1.3; 4.2) from Joppa in order to flee to a distant land (Is. 66.19). The land was rich in metals such as silver (Jer. 10.9), iron, tin, lead (Ez. 27.12), which were exported to places like Jope and Tire (Ez. 27). A region in the western Mediterranean where there are good mineral deposits would seem to be a likely identification, and many have thought of Tartessos in Spain. According to Herodotus (4.152), Tartessos was "beyond the columns of Hercules", and Pliny and Strabo located it in the Guadalquivir valley. By the way, the mineral wealth in Spain attracted the Phoenicians, who founded colonies there. Interesting clues come from Sardinia, where monumental inscriptions erected by the Phoenicians in the ss. IX BC contain the name Tarshish. WF Albright has suggested that the very word Tarshish suggests the idea of mining and smelting, and that in a sense any territory producing minerals could be called Tarshish, although it would seem more likely that Spain was the land in question. An ancient Semitic root found in theacrašāšu means "to melt", "to melt". It is possible that a derived noun, taršı̄šu , was used to define a smelter or refinery plant (ár. ršš , 'drip', etc., with reference to liquids). Hence, any place where mining or smelting was carried out could be called Tarshish.

There is another possibility regarding the site of Tarshish. According to 1 Kings 10.22 Solomon had a fleet of ships from Tarshish that brought gold, silver, ivory, monkeys and peacocks to Ezion-geber on the Red Sea, and 1 Kings 22.48 mentions that the ships of Jehoshaphat of Tarshish set sail from Ezion -geber towards Ophir. Furthermore, 2 Chron. 20.36 says that these ships were made at Ezion-geber to sail to Tarshish. These last references would seem to rule out any Mediterranean destination but at the same time indicate a place in the Red Sea or in Africa. The expression ˒°nı̂ ṯaršı̂š, Tarshish navy or Tarshish fleet, could more generally refer to ships that transported molten metal either to distant lands of Ezion-geber or to Phoenicia from the western Mediterranean. For the view that the ships of Tarshish were deep-drafted and known by that name because of the port of Tarsus, or thegr.tarsos , 'oar', see * SHIPS AND BOATS .

These ships symbolized wealth and power. A graphic picture of the day of divine judgment was to represent the destruction of these great ships on that day (Ps. 48.7; Is. 2.16; 23.1, 14). The fact that Is. 2.16 compares the Tarshish ships with the “precious paintings” (“loaded ships”, °BJ ; “precious ships”, °VP ) suggests that whatever the original identification of Tarshish was, in literature it became , as well as in the popular imagination, in a distant paradise where all sorts of sumptuous articles could be obtained in order to be carried to such places as Phenicia and Israel.

BIBLIOGRAPHY. S. Bartina, “Spain in the Bible”, °EBDM , t(t). III, cols. 161–163; L. García Iglesias, The Jews in ancient Spain , 1978, pp. 31–34; J. M. Blázquez, Tartessos and the Origins of Phoenician Colonization in the West , 1975.

WF Albright, "New Light on the Early History of Phoenician Colonization," BASOR 83, 1941, pp. 14ff; “The Role of the Canaanites in the History of Civilization”, Studies in the History of Culture , 1942, pp. 11–50,esp. pp. 42; CH Gordon, "Tarshish",IDB, 4, p. 517s.

Source: New Bible Dictionary

(4 and End)-TARSHIS

1. Grandson of Benjamin, son of Bilhan (1 Chr. 7.10) 2. One of the seven prominent princes of Ahasuerus, ruler of Persia (Est. 1.14).

3. Son of Javan, grandson of Noah (Gen. 10.4; 1 Chr. 1.7). The name Tarshish ( taršı̂š ) refers both to the descendants and to the land.

Several of the OT references relate to ships and suggest that Tarshish was on the seashore. So Jonah embarked on a ship that left for Tarshish (Jon. 1.3; 4.2) from Joppa in order to flee to a distant land (Is. 66.19). The land was rich in metals such as silver (Jer. 10.9), iron, tin, lead (Ez. 27.12), which were exported to places like Jope and Tire (Ez. 27). A region in the western Mediterranean where there are good mineral deposits would seem to be a likely identification, and many have thought of Tartessos in Spain. According to Herodotus (4.152), Tartessos was "beyond the columns of Hercules", and Pliny and Strabo located it in the Guadalquivir valley. By the way, the mineral wealth in Spain attracted the Phoenicians, who founded colonies there. Interesting clues come from Sardinia, where monumental inscriptions erected by the Phoenicians in the ss. IX BC contain the name Tarshish. WF Albright has suggested that the very word Tarshish suggests the idea of mining and smelting, and that in a sense any territory producing minerals could be called Tarshish, although it would seem more likely that Spain was the land in question. An ancient Semitic root found in theacrašāšu means "to melt", "to melt". It is possible that a derived noun, taršı̄šu , was used to define a smelter or refinery plant (ár. ršš , 'drip', etc., with reference to liquids). Hence, any place where mining or smelting was carried out could be called Tarshish.

There is another possibility regarding the site of Tarshish. According to 1 Kings 10.22 Solomon had a fleet of ships from Tarshish that brought gold, silver, ivory, monkeys and peacocks to Ezion-geber on the Red Sea, and 1 Kings 22.48 mentions that the ships of Jehoshaphat of Tarshish set sail from Ezion -geber towards Ophir. Furthermore, 2 Chron. 20.36 says that these ships were made at Ezion-geber to sail to Tarshish. These last references would seem to rule out any Mediterranean destination but at the same time indicate a place in the Red Sea or in Africa. The expression ˒°nı̂ ṯaršı̂š, Tarshish navy or Tarshish fleet, could more generally refer to ships that transported molten metal either to distant lands of Ezion-geber or to Phoenicia from the western Mediterranean. For the view that the ships of Tarshish were deep-drafted and known by that name because of the port of Tarsus, or thegr.tarsos , 'oar', see * SHIPS AND BOATS .

These ships symbolized wealth and power. A graphic picture of the day of divine judgment was to represent the destruction of these great ships on that day (Ps. 48.7; Is. 2.16; 23.1, 14). The fact that Is. 2.16 compares the Tarshish ships with the “precious paintings” (“loaded ships”, °BJ ; “precious ships”, °VP ) suggests that whatever the original identification of Tarshish was, in literature it became , as well as in the popular imagination, in a distant paradise where all sorts of sumptuous articles could be obtained in order to be carried to such places as Phenicia and Israel.

BIBLIOGRAPHY. S. Bartina, “Spain in the Bible”, °EBDM , t(t). III, cols. 161–163; L. García Iglesias, The Jews in ancient Spain , 1978, pp. 31–34; J. M. Blázquez, Tartessos and the Origins of Phoenician Colonization in the West , 1975.

WF Albright, "New Light on the Early History of Phoenician Colonization," BASOR 83, 1941, pp. 14ff; “The Role of the Canaanites in the History of Civilization”, Studies in the History of Culture , 1942, pp. 11–50,esp. pp. 42; CH Gordon, "Tarshish",IDB, 4, p. 517s.

Douglas, J. (2000). New Biblical Dictionary: First Edition. Miami: United Bible Societies.Source: New Bible Dictionary

Montuno

...como el Son...

Themes / Mythology

(1)- Tartessos: in search of the lost kingdom

Were the Tartessians Phoenicians?

Mythology Archeology Hispania

Credit: Photoaisa

1 / 7

The eastern influence

In goldsmithing, with the Phoenician presence, oriental motifs and techniques were introduced. Gold earring from the treasure of La Aliseda. VII century BC MAN, Madrid

Credit: Egmont Strigl/Age Fotostock

2 / 7

the phoenician metropolis

From the 9th century BC, the powerful Phoenician city of Tire established commercial contacts with the Tartessian world. In the image, ruins of the Roman Tyre.

Credit: Photoaisa

3 / 7

Warrior with shield and chariot

In the funerary steles of warriors found in Extremadura and Andalusia, a manifestation of the Tartessian culture has been seen. Stele of Solana de Cabañas. 8th-6th centuries BC MAN, Madrid.

Credit: Prism

4 / 7

Treasure of La Aliseda

The set of gold pieces found in La Aliseda (Cáceres), which was perhaps the funerary trousseau of a noble lady, allows us to clearly appreciate the Phoenician influence in the area of Tartessos. This is the case with the belt, which consists of more than sixty pieces in which oriental themes such as winged griffins, palmettes and a man fighting a lion have been represented.

Credit: Scala

5 / 7

In Solomon's time

Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Gilt bronze relief by Lorenzo Ghiberti. 1438-1440. Gate of Paradise, in the Florence Baptistery. Solomon, monarch of Israel, lived around 970-931 BC The biblical Book of Kings refers to the ships that the sovereign sent together with Hiram I from Tire to Tarsis, identified with Tartessos by many authors, and that returned loaded with precious metals and exotic products. The Phoenician emporium of Tire laid out a wide commercial network over the western Mediterranean, and it was precisely Tyrian navigators who founded Gadir (Cádiz), considered the first city in the West.Montuno's note: Error. Jaén is several millennia older; from the fourth millennium before Christ

Credit: Oronoz / Album

6 / 7

Bull skin

Gold pectoral in the form of bull skin, from El Carambolo. The almost three kilograms of gold found in 1958 on the El Carambolo hill, near Seville, preceded the excavation, between 2002 and 2005, of a sacred precinct built there in the 8th century BC, which was remodeled and enlarged in the following century. Although this sanctuary is of the Phoenician type, its altar in the form of an extended bull skin, which corresponds to the pectorals of the treasure that have the same shape, would constitute an original feature of the Tartessian world. The jewels that make up the El Carambolo treasure may have been ornaments for a cult image (perhaps they adorned sacred bulls) or priestly attributes.

Credit: Dagli Orti / Corbis

7 / 7

The arrival of the Phoenicians

Phoenician war ship, equipped with a spur to ram enemy ships. Gold earring dated around 404-399 BC The tradition that places the foundation of Cadiz around 1100 BC perhaps includes the first commercial contacts of the Phoenicians with Tartessos, since the excavations carried out between 2008 and 2010 on the site of the Comic Theater of this city place its birth later, between the end of the 9th century and the beginning of the 8th century BC In the previous period, the exchanges between the Tartessians and the Phoenicians, whose demands for metals and other goods would have transformed the indigenous societies, would have been consolidated.

Last edited:

Montuno

...como el Son...

Themes / Mythology

(2)- Tartessos: in search of the lost kingdom

According to the Old Testament, in the 10th century B.C. C. the ships of Solomon, the king of Israel , returned every three years laden with gold from a distant and mysterious place called Tarshish: "King Solomon had the ships of Tarshish in the sea with those of Hiram [king of Tyre], and every three years the ships of Tarsis arrived, bringing gold, silver, ivory, monkeys and turkeys" . The quote comes from the Book of Kings, written around the 7th century BC, but it takes us back three centuries, when the mineral opulence of the south of the Iberian Peninsula attracted the first Semitic navigators to the other end of the Mediterranean.

Most historians have it clear: the first author who mentioned Tarsis was referring to the commercial relations that the Israelites had with Tartessos , the kingdom located beyond the Pillars of Hercules (the Strait of Gibraltar), in the Lower Guadalquivir , which ruled the mythical king Argantonio. Since this first mention, the enigmatic aura around Tartessos has not faded. Travelers, philologists and archaeologists have searched for decades to find the remains of that civilization that flourished between 1000 and 500 BC, only to later disappear and fall into silent oblivion that lasted until recently , immersed in a nebula of uncertainties and guesses.

TARTESSOS AND ATLANTIS

Interest in the mysterious Tartessos dates back to ancient times. Various Greek historians and travelers from the 6th to 4th centuries BC recorded what was known, or believed to be known, about that civilization. Such was the case of Hecataeus of Miletus, Herodotus and, above all, Avieno, who in his Ora maritime spoke of a river called Tartessos that surrounded the island on which the city was located , also called Tartessos. Another author of the fourth century BC, Eforus, also referred to " a very prosperous market, the so-called Tartessos, an illustrious city, watered by a river that carries a large quantity of tin, gold and copper from Celtic ".To all of them was added an even more intriguing reference, that of Atlantis sung by Plato in his Dialogues, particularly in the Timaeus, and that many did not hesitate to identify with Tartessos. To what else could Plato be alluding when he describes Atlantis as "a great island, beyond the columns of Heracles, rich in mineral resources and animal fauna"?

Even contemporary archaeologists have believed to find the remains of Atlantis in the Tartessian region. But, for now, it is an impossible connection, based more on fables than on certainties. Such is the case of the thesis of the Frenchman Jacques Collina-Girard, who in 2001 located Atlantis on Espartel Island, halfway between Cádiz and Tangier; and of the sightings of Rainer Kuehne, who in 2004 said he had located with aerial images the remains of the "silver" temple consecrated to Poseidon and the "golden" temple erected in honor of Cleito in the Hinojos Marsh, near Cádiz.The first author who tried to accurately locate Tartessos was a philologist, Antonio de Nebrija, responsible for the first Castilian grammar

Apart from the question of Atlantis, the first author who tried to accurately locate Tartessos was a philologist, Antonio de Nebrija, responsible for the first Castilian grammar. In 1492, Nebrija identified Tartessos with the river Betis (Guadalquivir) and with the landscape of sea arms that the river formed at its mouth. But Nebrija's conjectures, emitted from intuition, did not have any type of archaeological support.

AFTER THE RICHES OF ARGANTONIO

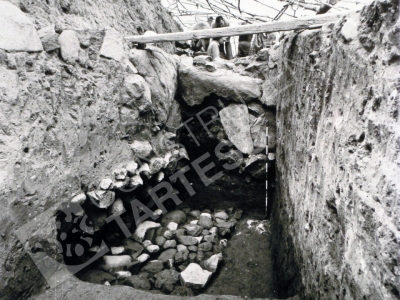

Archaeological research was delayed until the nineteenth century. The first to stir the Andalusian entrails in search of Tartessos was George Bonsor, an Anglo-French painter who was fascinated by the landscapes of Andalusia and who, from the 1880s, changed canvas and watercolor for pick and shovel as soon as he verified the archaeological potential that spread out under his feet. No one had taught him to dig, but his illusion was stronger than his inexperience. Bonsor recovered a cache of Tartessian pieces in various Seville necropolises such as Cruz del Negro, Carmona, Setefilla and Cerro del Trigo.Bonsor was followed by the German Adolf Schulten, a great promoter of research at the Numancia site, from where he was at odds with the Spanish cultural authorities. Schulten wanted to follow the example of his compatriot Schliemann, who had unearthed Troy thanks to his faith in classical sources. Avieno's Ora Maritime would be to Schulten what the Iliad had been to Schliemann; and the Coto de Doñana would serve as the hill of Hissarlik, in Turkey, where Schliemann found, in 1873, the Troy sung by Homer.

Schulten intended to prove that Tartessos lay in the Doñana Marshes and took action with the help of Bonsor. He got hold of the necessary tools and led the ambitious adventure of locating Tartessos there. But in the end the only thing he found was some ruins from Roman times in the so-called Cerro del Trigo. Schulten failed, but his contribution was nonetheless important. His work Tartessos, published in 1924, served to order all the knowledge that was had about the ancient civilization of the Guadalquivir and constituted the starting point for later investigations.Schulten's work served to order all the knowledge that was had about the ancient civilization of the Guadalquivir

All the testimonies left by the sources refer to Tarsis or Tartessos as a civilization with a metallurgical soul: "The most elegant of markets, the city of gold and silver...". So much so that Argantonius, the quintessential Tartessian king, has silver (Arg-) incorporated into his name.

But the literature was elevated to archaeological certainty on September 30, 1958, the day that a gang of workers who worked on the land of a hunting club in Seville -the Royal Pigeon Shooting Society-, in the town of Camas , four kilometers west of Seville, made a sensational discovery: a clay container in which 16 plaques, two bracelets, two pectorals and a necklace appeared. All the pieces were solid gold and weighed almost three kilos. After analyzing them, the archaeologist Juan de Mata Carriazo concluded that it was "a treasure worthy of Argantonio".

The discovery of the treasure of El Carambolo (it was named after the 91-meter-high hill, of this name, on which it was found) stirred up scientific forums when many were already resigned to a virtual Tartessos. The Carambolo became the leading image of the Tartessian culture and Juan de Mata Carriazo, the godfather of the discovery. For three years, Mata Carriazo excavated the site that represented the tangible Tartessos. He unearthed walls, studied ceramics, compared stratigraphic levels and finally demonstrated that Tartessos was not a hallucination of ancient authors.

In this way, scholars were able to define a map of the Tartessian civilization, which extended across the southern half of the Peninsula. Various sites were thus associated with Tartessos: in the province of Huelva, those of La Joya and Cabezo de San Pedro; in Seville, El Gandul and Carmona; in Córdoba, the Hill of the Burned; in Bajadoz, Medellín and Cancho Roano, and even in Portugal, the site of Alcácer do Sal is considered Tartessian. The Cadiz town of Mesas de Asta, the Roman Asta Regia, should also be included in the Tartessian area. The term Regia is an interesting clue to the type of political organization of the Tartessian world; Researchers such as Manuel Bendala suspect that some Tartessian elite ruled these lands before Rome named them.

In recent years, the question that has provoked the most debate about the culture of Tartessos is its relationship with the Phoenician world. Starting in the 8th century BC, Phoenician navigators and merchants founded cities and factories in the south of the peninsula , especially in the provinces of Malaga, Granada, Cádiz, Almería and Alicante; a territory, therefore, very close to that of the Tartessians, with whom the Phoenicians undoubtedly maintained contacts of all kinds, both economic and cultural and artistic.

Last edited:

Montuno

...como el Son...

Themes / Mythology

(3 and End)- Tartessos: in search of the lost kingdom

TARTESSIANS OR PHOENICIANS?

Traditionally, it has been thought that both areas, despite their geographical proximity and the relationships established between them, remained substantially independent of each other. The Tartessian nuclear territory has traditionally been located far from the coast, while the Phoenician is associated with the Andalusian and Alicante coast. However, some scholars today argue that there was an authentic cultural fusion between Tartessians and Phoenicians, to the point that in archaeological terms it is very difficult to distinguish on many occasions which elements are Tartessians and which are Phoenicians.This is precisely the theory held by two Sevillian archaeologists, Álvaro Fernández Flores and Araceli Rodríguez Azogue, who between 2002 and 2005 excavated at the El Carambolo site, expanding the research that Mata Carriazo had carried out decades before. In his opinion, El Carambolo would not be an indigenous settlement, a product of the Tartessian civilization, but a Phoenician sanctuary , dedicated to the goddess Astarte, which reached its maximum splendor in the 7th century BC and was abandoned in the following. A sentence that reduces Tartessos to imaginary props and whose shock wave has shaken the scientific community.

Both authors maintain that the area of colonial expansion of the Phoenicians even extended to Extremadura. They believe that the objects baptized as Tartessian (among them, the treasure of El Carambolo itself) are the colonial expression of a Semitic people that settled in Cádiz around the 10th century BC and later expanded along the coast and the interior of the peninsula. In this way, El Carambolo would be a Phoenician sanctuary, the result of a certain "miscegenation" between the Semitic and the local. It could be compared to the Spanish colonization of America after the arrival of Christopher Columbus. If one contemplates the footprint left by the Spanish in cathedrals or churches in Latin America, would he classify them as Spanish or local works?

A recent congress, held in Huelva in December 2011, has given resonance to the positions of the "tartessosceptics", those who doubt that Tartessos can be considered as a differentiated culture. The debate has even moved to the showcases of the Archaeological Museum of Seville. There, also since December 2011, the pieces of the El Carambolo treasure have been exhibited, which for decades had been safely stored in a bank safe. But now visitors read a new appellation of origin: Phoenician.

However, for most specialists, the opinion of Fernández Flores and Rodríguez Azogue errs on the side of daring. They believe, on the contrary, that specifically Tartessian features can be seen in El Carambolo. Evidence of this would be found in the bull-skin-shaped altar that has appeared in the epicenter of the sacred precinct, the same shape as the pectorals of the treasure of El Carambolo. In no Phoenician sanctuary are altars with this profile; only in Hispanic territory.

Other altars from the Tartessian area have the same shape as the one found at Carambolo, such as those at Cancho Roano (Zalamea de la Serena, Badajoz) and Cerro de San Juan (Coria del Río, Seville). The Greek myth tells that Hercules, after killing the giant Geryon –the first king of Tartessos, according to legend–, appropriated his herd of red bulls, in which he was the tenth of the twelve labors attributed to the Greek hero. Thus, the bull is Tartessos' safe-conduct so as not to burn on the pyre of historical inventions.

TO KNOW MORE

Tartessos unveiled. The Phoenician colonization of the peninsular southwest and the origin and decline of Tartessos. Álvaro Fernández Flores and Araceli Rodríguez Azogue. Almuzara, Cordoba, 2007.Tartessos. Contribution to the oldest history of the West. Adolf Schulten. Almuzara, Cordoba, 2006.

Tartessos. Jesus Master of the Tower. Edhasa, Barcelona, 2003 (novel).

Tartessos: el enigma del reino perdido de la Península Ibérica

El origen de la enigmática cultura orientalizante del sur de la Península Ibérica ha dado pie a un sinfín de hipótesis, ¿eran fenicios o tal vez sean la Atlántida perdida de Platón? Lo más probable es que se trate de una cultura local.

Last edited:

El Timbo

Well-known member

yesare you referring to paleo?

Cuddles

Well-known member

you mentioned that it´s been great for you,what kind of positive changes have you noticed?

I have never had the chance to actually ask someone who´s tried it directly and I´m very curious

Montuno

...como el Son...

España

David Rubio

27 March, 2020

"Tartessos, city of Iberia, named after the river that flows from the mountain of silver, a river that also carries tin". Hecataeus of Miletus , 6th century BC.

"And since the river has two mouths, it is said that the city of Tartessos, the river's namesake, was formerly built on the land placed between them." Strabo , 1st century BC.

Greek literary sources have often been the light that has guided archaeologists in their search for sites that explain the ancient history of the peoples of Europe. In some cases, the archaeological campaigns were successful in unraveling mysteries and debunking myths.

Although Tartessos still has a lot of legend and little history , excavations at sites such as Turuñuelo (Badajoz) are marking a turning point that could be definitive. Will we discover once and for all the origin, development and disappearance of the most mysterious civilization in Western Europe?

Turuñuelo site (Badajoz), the great hope in the study of Tartessos:

Turuñuelo site (Badajoz), the great hope in the study of Tartessos:

A two-story building from 2,500 years ago may be the missing link in Tartessian culture. Around it human bones, vessels, plates, remains of sculptures and many animals: bones of more than 20 horses, 3 cows, pigs, sheep... All of them sacrificed in a ritual ceremony? comparable only to those described in the Old Testament. But the archaeologists prefer to highlight the building, characterized by its monumental staircase "unique in the western Mediterranean at the time" .

The Turuñuelo excavations began in 2015 and soon reached the level of the famous Cancho Roano site, also in Badajoz, until claiming for itself the title of “the most important archaeological site in Spain” . With a grant from the Diputación de Badajoz, the work continued until the first great discoveries arrived in 2018.

And the controversies:

Among them the refusal of the owners of the land to allow the entry of more archaeologists while trying to sell the site at a price that "completely exceeded the limits of the value of the land", according to the Junta de Extremadura . While the negotiation for the purchase of the site comes to a successful conclusion, the "Building Tartessos" project , which revolves around Turuñuelo, will try in the coming years to illuminate the myth, definitively transforming it into History, with a capital letter.

Because what do we know so far about Tartessos? On what points do most historians and archaeologists agree? Not in too many… At the beginning of this decade a congress was held in Huelva in which the majority of historians specialized in the matter tried to reach “a minimum consensus” . Both the defenders of Tartessos as a great peninsular civilization, and the supporters of Tartessos as a hybrid culture between indigenous people and Phoenician settlers tried to lay the foundations for that more scientific and less literary "Building Tartessos".

“Bronze Carriazo”. Archaeological Museum of Seville. One of the most famous pieces of the Tartessos civilization.

“Bronze Carriazo”. Archaeological Museum of Seville. One of the most famous pieces of the Tartessos civilization.

Thus, it is accepted that Tartessos was a culture of the peninsular southwest , confluent with the Phoenician colonial presence that starts around the IX BC , that reaches its splendor in the VIII and VII centuries and that loses strength towards the V. It was not wanted to certify its disappearance due to a great war or a natural disaster (there is no evidence in either direction) and it was not assumed that Tartessos was a unified empire under a hereditary monarchy, as suggested in the first studies on this civilization based on the figure of Argantonius , the only Tartessian king who appears —probably mythologized— in Greek literary sources.

Although these conclusions were perhaps a jug of cold water for fans of the legends, (almost) no one questioned the existence of this culture. Tartessos existed —although it is still unknown in what dimension— as shown by the different archaeological sites that, in relation to the Greek literary sources, are shaping the definitive panorama of this civilization.

Estimated map on the expansion of the Tartessian culture.

Estimated map on the expansion of the Tartessian culture.

And where was Tartessos?:

leus of this culture would be located between present-day Huelva and Seville at a time when the sea level was higher than the current level, creating a gulf —known as the Tartessian Gulf— that occupied a large part of Doñana and the marshes of the Guadalquivir. Precisely this river is the one known as Tartessos by the ancient Greeks.

While on the coast there were Phoenician colonies such as the famous Gadir (present-day Cádiz), inland is where that civilization known as Tartessos would be located, which could have spread to the south of present-day Extremadura —as the Badajoz deposits show— and also in the southern part of Portugal.

The coexistence of Phoenician colonies and Tartessos and the great similarities between the majority of archaeological remains found in the Tartessian sites with the style of the Phoenician metropolis is the main cause of historiographical controversies, with some radical historians even denying the existence of Tartessos as a civilization . autochthonous: for them, Tartessos would be the consequence of a process of acculturation of the peninsular peoples by the Phoenician settlers.

The Pillars of Hercules in Ceuta (Spain), on the southern or African side of the Strait of the Pillars of Hercules (aka of Tarifa, aka of Gibraltar)

The Pillars of Hercules in Ceuta (Spain), on the southern or African side of the Strait of the Pillars of Hercules (aka of Tarifa, aka of Gibraltar)

But it is that Hercules would also have passed through Tartessos being a cornerstone of the myth of this peninsular civilization: "Hercules on his journey through Europe to kidnap the herd of Geryon was destroying many wild beasts wherever he passed and finally set foot in Libya (African coasts), and passing to Tartessos, he erected as a symbol of his journey two columns facing each other on each side”. Gerioneida of Stesichorus, 6th century BC.

Those Pillars of Hercules also appear in Plato's Timaeus when referring to Atlantis . Despite the fact that this mythical island supposedly full of wonders has been located in dozens of enclaves according to the interpretation made of the Platonic narrative, the reference to the Pillars of Hercules made some historians see in Tartessos the origin of Atlantis.

In this sense, the French geologist Marc-André Gutscher from the University of Western Brittany even stated in a study published by the journal Geology that he had discovered remains in the Strait of Gibraltar that would coincide with the mythical Atlantis and that they could belong to the Tartessian empire. . Almost nothing…

www.descubrir.com

www.descubrir.com

Tartessos, the peninsular civilization that fascinated the Greeks:

We travel back in time to try to reveal one of the greatest mysteries in the history of pre-Roman Hispania: Tartessos, a mythical civilization located in the southwest of the peninsula, which fascinated the ancient Greeks and still puzzles historians today.David Rubio

27 March, 2020

"Tartessos, city of Iberia, named after the river that flows from the mountain of silver, a river that also carries tin". Hecataeus of Miletus , 6th century BC.