Black Afhani - Kandahar USC @Cristalin

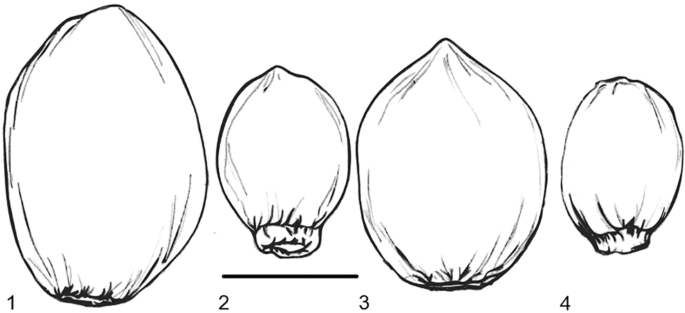

Figure 5.

Type specimens of C. sativa subsp. indica var. afghanica. Neotype on left (a), epitype on right (b).

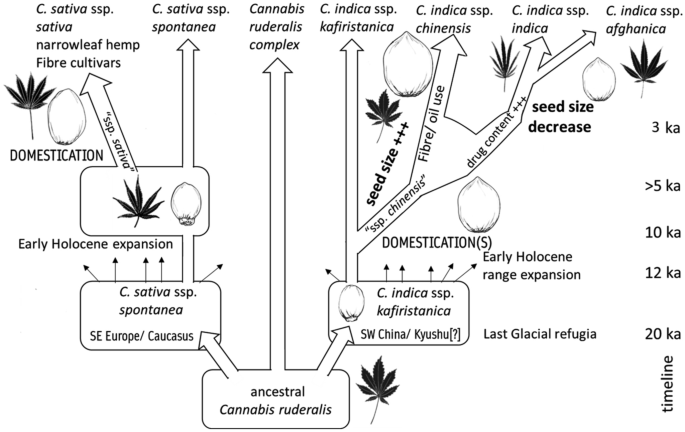

A classification of endangered high-THC cannabis (Cannabis sativa subsp. indica) domesticates and their wild relatives

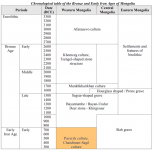

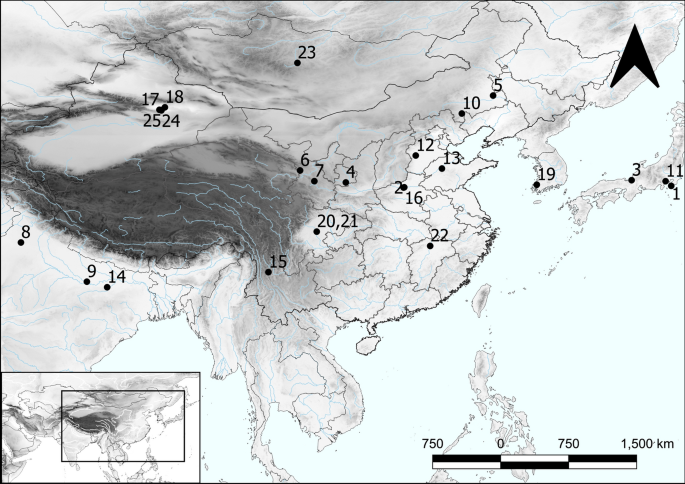

Two kinds of drug-type Cannabis gained layman’s terms in the 1980s. “Sativa” had origins in South Asia (India), with early historical dissemination to Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Americas. “Indica” had origins in Central Asia (Afghanistan, Pakistan, Turkestan). We have assigned unambiguous...

phytokeys.pensoft.net

Last edited: