"mistakes were made" science is in a constant state of flux/evolution. until we know everything (after that as well), mistakes will continue to be made. this is not a reason to not TRY to eliminate fuckups though...and we still need to learn from our previous errors. kind of like a really twisted "groundhog Day".this generation will be credited with decisions

top of the heap to third world status in one generation

- Thread starter Thread starter Gry

- Start date Start date

Eltitoguay

Well-known member

"There is nothing more imperative than the left, and whatever billionaires aligned with it who are willing to make the investment, creating a strong, influential, independent media that rivals the vast reach of the propaganda networks on the right (...)"

This can be a double-edged sword, no?... And even more so if in capitalist language, an "investment" expects a "rate of profit"... Furthermore, the big millionaires can only expect from the true left, greater state control over their businesses, and taxes on their profits... And few millionaires have enough socio-political awareness to earn less, even if they truly believe that this is fair, as well as best for their society...

It is better if they give non-refundable donations without expecting to be able to influence the media to which they donate.

I believe that the true left should continue to try to penetrate the Democratic Party as much as possible, introducing as much of its political agenda as possible, so that people can observe those policies in action and judge whether they do not improve their lives enormously compared to the ultra-right and autocratic drift of the Republican Party.

View attachment 19066139

MAY 2020

The American Left after Sanders :

View attachment 19066140

The consequences of Bernie Sanders' strong performance in the primaries will not be easily dispelled. To a large extent, he won the "battle of ideas" within the Democratic Party and managed to shift it to the left. A strong debate is now looming over the strategies that the left should adopt and how to intervene in the always complex scenario of the Democratic Party.

Figures such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez embody the generational change.

Patrick Iber ; May 2020.

Since 2015, Bernie Sanders has been the standard-bearer of the left in the United States.

When he announced his candidacy for the presidency, only a few believed that it would be anything more than a protest campaign. Sanders described himself as a “democratic socialist” and called for a “political revolution,” positioning himself far outside the boundaries of traditional American politics. He was not even a formal member of the Democratic Party, although he was running for the presidential nomination for that party. Five years later, in early 2020, he was, for a time, the favorite in the race for the Democratic nomination.

Bernie Sanders - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

View attachment 19066149

Sen. Bernie Sanders at a rally at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, on Feb. 18, 2020.

In the 2020 Democratic primaries, the incumbent senator from Vermont performed well in the first three of the four early voting states . All told, he tied in the Iowa caucuses , won the New Hampshire primary, and won again in the Nevada caucuses, where he received strong support from working-class Latino voters. By then, projections had him as the Democratic front-runner. Then, in late February, Joe Biden, Barack Obama’s vice president who is considered a politically moderate Democrat, won South Carolina, the first early state with a significant African-American population. In an instant, many of the remaining candidates dropped out of the race, and on March 3, which is known as “Super Tuesday” because of the number of states holding simultaneous primaries, Biden dominated the scene. Sanders’ path to the nomination faded away.

While he remained in the race, Sanders demonstrated that the electorate for a social democratic agenda in the United States was much larger than most expected, but at the same time not large enough to stage what would have essentially been a takeover of the Democratic Party. Although his age will not allow him to run again, the consequences of his strong showing will not be easily dissipated. Sanders has largely won the “battle of ideas” within the Democratic Party, shifting it substantially to the left. But how American left organizations will seek to move forward in a post-Sanders era remains a matter of heated debate.

The strategy moving forward depends in part on whether you believe Sanders actually had a chance of being elected or, rather, that his chances of winning were illusory. Some Sanders supporters remain bitter that the party establishment favored Hillary Clinton in the 2016 primary, feeling that it tilted the playing field in their favor. In 2020, they again saw the Democratic establishment unify around Biden, who had struggled to generate enthusiasm, rally volunteers and secure donations. “What the establishment wanted was to make sure that people would unite around Biden so they could beat me,” Sanders said . Candidate Pete Buttigieg, for example, who had tied with Sanders in Iowa, dropped out after a phone call with Barack Obama . Amy Klobuchar did the same, and the support of Klobuchar and Buttigieg was essential in boosting Biden against Sanders on Super Tuesday.

Many on the left, skeptical that the Democratic Party is truly a vehicle for progressive change, feel their candidate was simply unacceptable to the party.

From a party perspective, there is little mystery in this. Sanders was not a formal member of the Democratic Party, but chose to remain independent throughout his political career as a senator.

This may have been an advantage in the general election to appeal to voters alienated from the party, but it was certainly not an advantage in the primaries, where most voters, almost by definition, identify as Democrats. In addition to programmatic divergences and hostility from party elites, who feared the implementation of Sanders’s program, there were also ordinary voters who feared that choosing him as the Democratic candidate would prove too risky in a year when the bottom line is defeating Donald Trump. (Polls suggested that both Sanders and Biden could beat Trump with roughly equal odds in the November election, but this did not allay fears that running a “socialist” might not be a smart political move.) Even those who supported much of Sanders’s agenda did not see him as capable of successfully implementing it. Among his most ardent supporters, little attention was sometimes paid to the problems he would have faced if elected, from “investment strikes” to various forms of political obstructionism. In the end, both the Democratic Party establishment and the majority of voters rejected Sanders. He mustered the support of just over 30% of voters, which would have only served to win in a divided arena. Once the competition was reduced to just two candidates, his chances all but disappeared.

There was, perhaps, some chance in February, when another outcome was still possible. Sanders was and remains very popular and seen as genuine, but in taking the lead he had to prove that he could be the candidate not just of the left but of the entire party. Had enthusiasm continued to grow, perhaps the party would have had to accept him. But Sanders continued to rival the Democratic Party itself, making it difficult to imagine that he could unite it after victory. He received little support from African Americans, the group most loyal to the party and some of those who had the most to lose. Culturally, his campaign remained wedded to the left in a way that did not allow it to forge the necessary coalitions.

In my case, for example, I returned to my home state of Iowa to canvass door-to-door for Sanders before the caucus . As part of that campaign work, I attended a rally of more than 3,000 people in Cedar Rapids—a city well known for the smell of oatmeal, due to a factory located just outside. In addition to a speech by Sanders himself, the rally featured a performance by the band Vampire Weekend and prominent figures such as filmmaker Michael Moore and Marxist philosopher, theologian, and African-American human rights activist Cornel West. The crowd was enthusiastic, but I left worried: there were probably more volunteers from other states than people from Iowa. I also noticed the absence of a plan to expand the movement beyond the left (represented by figures like Moore and West, who are highly respected but don’t mean much outside that space) and young people (represented by the many popular bands, like Vampire Weekend, who played for free at the Sanders campaign). The next day, speaking to voters door-to-door, I met many who had supported Sanders in 2016 but now thought Elizabeth Warren or Buttigieg were a better choice.

Sanders needed to broaden his appeal beyond those who identified with “socialism.”

But it wasn’t simply a matter of convincing people of the candidate’s merits: it was a matter of persuading skeptics that they had a place in his campaign and that his strategy of change would pay off. Sanders claimed that he was the only one who could bring young people and disillusioned abstentionists to the polls. But those groups did not mobilize in early voting states in a way that would fundamentally change the race. At the same time, relations soured between different groups of voters. Warren, the second-most progressive candidate in the primaries, gathered around her a loyal group of supporters represented by highly educated progressive professionals. Warren’s campaign gained considerable momentum in late 2019, when Sanders was still recovering from a heart attack. As she topped the polls for the first time, many pro-Sanders outlets, such as Jacobin magazine , launched attacks on Warren, eroding relations among her supporters. The kind of online behavior of some Sanders supporters was seen as rude , which may have deterred some from joining the campaign. Fundamentally, the identity of the left has been built around the shortcomings of “liberalism”—in its American sense, where it is more or less synonymous with progressivism—making it difficult to imagine how to forge the necessary coalition with the more moderate wings of the Democratic Party.

View attachment 19066155

Sanders at a campaign rally in Michigan.

There were voices within Sanders’s campaign urging him to find ways to expand beyond his traditional base, but the candidate was finding it difficult to change the message that had taken him this far and that he had been advocating with great consistency since the 1960s. I saw some of this firsthand. During the primaries, I served as a campaign consultant, part of the foreign policy advisory team. (In my day-to-day life, I teach U.S. and Latin American history at the University of Wisconsin.) I had no direct contact with Sanders, no access to behind-the-scenes discussion or debate. But I was available to help craft messages and proposals in an area where Sanders had to tread carefully. He comes from the anti-imperialist tradition of the American left, and his critics have been eager to link him to Venezuelan “socialism.” Overall, I think he handled the campaign well, making clear that he had no interest in defending authoritarian governments, while emphasizing the need to establish a relationship with Latin American countries based on equality and nonintervention and criticizing the way the Trump administration's bluster helped entrench hard-line figures in the region.

But when Sanders began to lead in the polls, he inevitably faced increased scrutiny. One interviewer released a tape of Sanders from the 1980s in which he explained that Cubans had not rebelled against Fidel Castro during the U.S.-sponsored operation to overthrow him at the Bahía Cochinos (Bay of Pigs), saying that “he educated the children, he gave them health care, he completely transformed society.”

All of that is fairly accurate. When presented with the clip, Sanders responded, “We are totally opposed to the authoritarian nature of Cuba, but it would be unfair to say that it’s all wrong.” Again, nothing false: but it seemed to many people (and headline editors) that Sanders was praising Fidel Castro. This raised questions about both his views and his chances of being elected. What kind of socialist is he? Liberal journalist Chris Matthews practically had a nervous breakdown on live television, pontificating: “I think if Castro and the communists had won the Cold War there would have been executions in Central Park and I might have been one of those executed. And there would have been people celebrating.” Matthews, who certainly had no such doubts , said he was not sure whether Sanders’ vision of “socialism” resembled that of Cuba or Denmark. At the very least, this controversy was perceived as a major liability in Florida, an important state in the general election. In a state with many anti-Castro Cuban opinion-mongers (not to mention Venezuelan and Nicaraguan migrants, etc.), these statements constituted proof that Sanders either did not recognize the essentially repressive nature of Castro’s government, or that he was caught up in revolutionary nostalgia.

Invasión de bahía de Cochinos - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

es.wikipedia.org

I spent a few feverish days trying to provide Sanders with a set of ideas on how to approach the issue. In my view, he should avoid talking about Castro, use questions about these remarks as an opportunity to make his ideas about socialism clearer while explaining that people did not have to identify as “socialists” to support his campaign. He could highlight his long and well-documented defense of civil liberties in the United States. He could emphasize the setback that Trump’s policies represented regarding the Obama administration’s diplomatic opening toward Cuba and how this served to reinforce the most repressive wing of the Cuban government.

As a candidate, Obama also faced accusations—many of them racially charged—of being out of touch with mainstream American politics. In 2008, a video of his church pastor, Jeremiah Wright, saying “God damn America” surfaced, and Obama responded with a moving, nuanced speech about the complexities of race in the country that distanced him from his pastor and displayed great political skill. This calmed fears about Obama’s “unelectability” and showed that he knew how to navigate the obstacles put in his way. I thought the Cuba issue would give Sanders a similar opportunity that we could take advantage of. But in a debate a couple of days later, he basically reiterated his previous position, circling around criticizing American interventionism in Latin America. Again, everything he said was true, and even morally correct, but it fed into a broader perception, I think, that he didn’t have the skill he would need in the months ahead. Among other things, this made him an “unacceptable” candidate in the general election, leading voters and the party to their verdict on Super Tuesday.

In 2016, Sanders stayed in the primary race even when it was clear he had no chance of winning, seeking to maintain his influence on the party platform. This year, he made a different choice. The spread of the coronavirus and the various forms of lockdowns and social distancing put in place to combat it made voting dangerous. (Still, in Wisconsin, where I currently live, the Republican legislature and judges rejected the Democratic governor’s attempts to delay the election until it could be held safely.) Because of the staggered primary voting schedule, many states still had elections pending. Rather than put people at risk, Sanders dropped out of the race and decided to throw his support behind Biden.

Although Sanders and Biden have been personal friends for some time, Biden does not have much credibility on the left. He has a reputation as a mainstream Democrat. But he has come to realize that the support and enthusiasm Sanders generated has become a significant part of the party, and he must adapt to this new context. Against the backdrop of multiple crises, including the federal government’s catastrophic response to the Covid-19 pandemic and the potentially destructive effects of climate change, many young voters fear that Biden does not share their sense of urgency. But unlike Clinton in 2016, Biden has invited members of Sanders’ campaign staff to join his team . Biden has also tried to incorporate some of Sanders’ and Warren’s policy proposals, hoping to generate some enthusiasm among Sanders’ youthful base . In May, Biden and Sanders jointly announced the formation of unified task forces to develop the party’s policy platform , with three out of eight members chosen by Sanders.

During the pre-campaign, Biden struggled to attract large, enthusiastic crowds. But with the coronavirus making large campaign events impossible, mass gatherings are likely to be less relevant to the November results. In my hometown of Madison, I have yet to see a lawn sign supporting Biden, but I did see a few in support of “Any Able-Bodied Adult 2020.” Current polls suggest that lying low and not being Trump should already be a winning strategy, though the 2016 result warns against overconfidence.

Organizations on the left, meanwhile, are divided.

The Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) has refused to endorse Biden. Critics say this decision will doom DSA to irrelevance in the years to come (although it is unclear whether Biden would have wanted or benefited from DSA’s endorsement).

Some socialists see Sanders’s defeat as a sign of the limits of such electoral strategies within the Democratic Party and have pinned their hopes on a third party. However, beyond a few prominent commentators, the vast majority of Sanders’ supporters will vote for Biden in November. The mixed response on the left in some ways shows that the “cult of Bernie” imagined by some critics was no such thing: his supporters are thinking for themselves and not even necessarily following the lead of Sanders, who has been clear on the importance of electing Biden. But whatever they do, members and organizations on the left will have to look to the future.

Democratic Socialists of America - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

Sanders has brought many leading lights of the American left into positions in the political world that were unthinkable a few years ago.

Among them, perhaps, is his likely successor as the symbolic leader of the American left: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

View attachment 19066163

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

Unlike Sanders, Ocasio-Cortez is not ambiguous about her place in the Democratic Party, although she said in January that “in any other country, Joe Biden and I would not be in the same party, but in America we are.”

View attachment 19066164

It is a statement that sums up the challenge that the American left will always face: without constitutional reforms or changes to the electoral system, it will have to participate in a party that is not a left-wing party. Still, there are those who are hopeful. In May, it was announced that Ocasio-Cortez will serve on the special advisory body on climate change. And, looking to the future, she possesses formidable political talent. “The way she expresses herself seeks to create a majority on terms that Bernie is not interested in,” said Max Berger, a progressive member of Warren’s team. “If Bernie is Moses, then Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is Joshua.”

In this case, perhaps someone less burdened by the legacy of the past will be able to carry the flag of the future.

View attachment 19066160

La izquierda estadounidense después de Sanders | Nueva Sociedad

Las consecuencias del gran desempeño de Bernie Sanders en las primarias no se disiparán fácilmente. En gran medida, ganó la «batalla de las ideas» dentro del Partido Demócrata y logró desplazarlo hacia la izquierda. Ahora se avecina un fuerte debate sobre las estrategias que deberá adoptar la...nuso.org

View attachment 19068027

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

The pragmatism of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez:

The congresswoman has moderated her rhetoric in the five and a half years since she was elected and has evolved from the margins to the center of the Democratic Party.

Democratic Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez speaking at the U.S. House of Representatives.

JAVIER DE LA SOTILLA; WASHINGTON; 09/16/2024

A week after winning her election to Congress for her New York district , Democrat Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez staged a sit-in with 200 other climate activists in 2018 at the office of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. The youth revolt, which demanded that the Democratic establishment make the climate emergency a priority, was a statement of intent: a new progressive generation had arrived at the Capitol to challenge the party establishment .

Alongside Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley and Rashida Tlaib, the American left had managed to increase its share of representation in Congress, under the spiritual leadership of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, and had united in a hopeful group of young politicians who called themselves The Squad. That generation, which prided itself on being independent of the powerful lobbies of the fossil industry, carried the Green New Deal energy transition as its banner and, making trouble from the margins of the party, sought far-reaching transformations in an aging Congress.

Two years later, at the 2020 Democratic convention, Ocasio-Cortez had just 90 seconds to endorse Sanders in the Democratic primaries.

The party, fearful that a left-wing candidate would alienate moderates and facilitate Donald Trump’s re-election, threw its support behind Joe Biden, who went on to win the nomination and the election in November. After his victory, the Democrats signed a truce, and Biden and Sanders created joint working groups to define the policies of the new administration. Ocasio-Cortez participated in those decisive meetings.

Four years later, at last month’s Chicago convention, the progressive gave a prime-time speech lasting more than half an hour , preceding former candidate Hillary Clinton and winning over thousands of attendees, who chanted her name as she defended Biden’s mandate, Kamala Harris’ presidential ambitions and warned of a return of Trump, who “would sell this country for a dollar if it meant lining his pockets and greasing those of his friends on Wall Street.”

That speech, more focused on the dangers of the Republican than on the defense of progressive policies, was the signature of the pragmatism of a politician who aspires, in her own words, to “change the party from within” and progressively gain power shares in the Democratic apparatus. This does not imply a change in her ideology, but an adaptation of her speech: if before she addressed the young university students of New York, now she addresses an entire country and praises a candidate who defends the extraction of oil through fracking, rejects universal public health care and promises to limit the right to asylum and to deploy more national guards on the border.

The Democratic Socialists of America, the party's leftmost group, withdrew its support for his stance on Israel.

Ocasio-Cortez was one of the first congresswomen to speak out against what she called a “genocide” in Gaza and called for an end to the military aid to Israel that the Biden administration is defending. But those differences have not prevented her from giving her unconditional support to Harris, which has earned her criticism from the pro-Palestinian sector. While she assured inside the United Center stadium in Chicago that Harris is “working tirelessly to secure a ceasefire in Gaza and bring the hostages home,” thousands of protesters outside the venue chanted at her and other members of the Squad as one of the facilitators of the massacre of more than 40,000 Palestinians.

In response to these stances, the Democratic Socialists of America, the leftmost group in the Democratic Party, withdrew their support for her re-election to Congress on November 5, when, in addition to the White House, the entire House of Representatives and a third of the Senate will be up for renewal. In a long statement, the socialists accused her of “deep betrayal” after participating in an event with leaders of the Jewish community against “anti-Semitism” in the protests that have proliferated this year on university campuses across the country. At a recent event in the Bronx with Senator Sanders, dozens of protesters interrupted her speech to accuse her of being a “fraud.”

Democratic Socialists of America - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

Ocasio-Cortez's pragmatism is explained by the exceptional political moment the country is experiencing and by the party's urgency to show itself united in the face of an ulterior evil: Trump's victory in the elections. The congresswoman has evolved from activism to institutional politics in the five and a half years she has been serving in Congress, during which she has held leadership positions on the House Oversight and Accountability Committee, as well as on the Natural Resources Committee, from which she has worked hand in hand with the Biden Administration in the development of legislation.

Over the past six years, the left has expanded its representation, with the election of members such as Jamaal Bowman, Cori Bush, Greg Casar and Summer Lee, but it has become more institutionalised and its discourse has moderated. The truce within the Democratic Party, which tries to hide its deep divisions on social, environmental and geopolitical issues, will continue until the November elections, which will decide the future of the country and the party itself. If the centrist turn that Harris has also taken in her speeches proves ineffective in the elections, in the event of a Trump victory, it is expected that the Squad will revive the combative spirit that characterised its origins and push the party, once again, to the left.

Read also

Kamala Harris defends her pivot to the center in her first interview as a candidate on CNN

JAVIER DE LA SOTILLA

The Democratic Unity Convention Against the Cult of the Republican Leader

JAVIER DE LA SOTILLA

Harris leads in polls after debate, but holds back hope: “We start at a disadvantage”

JAVIER DE LA SOTILLA

Trump vows “mass deportations” of Haitian migrants after claiming they eat pets

EUROPA PRESS

El pragmatismo de Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

Una semana después de ganar las elecciones al Congreso como representante de su distrito de Nueva York, la demócrata Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez organizó en el 2018 unawww.lavanguardia.com

I'm sure that if the working class and/or poor Trump voter could suddenly experience a Universal Health System like in other countries, he would think twice before voting for Trump again. ...And while this happens, I'll try to make they think a little: How is it possible that the world's leading economic and geostrategic power, speaking, has a life expectancy at birth, 6 lower than the (at most) twentieth?

1962 :

2022 :

Comparar economía países: Estados Unidos vs España Esperanza de vida al nacer 2025

Comparativa de países. Comparativa de los datos macroeconómicos y socio-demográficos de países. Aquí tienes la comparativa de Estados Unidos vs España, Esperanza de vida al nacer

Health expenditure per capita in selected countries in 2022(in dollars) :

USA : 12.555Spain: 4.461

Gasto sanitario per cápita por país en 2022| Statista

Esta gráfica muestra el gasto sanitario per cápita en países seleccionados en 2022.

Last edited:

Eltitoguay

Well-known member

...It would also be interesting to be able to limit private funding to political parties by individuals/companies/organisations, which could then act as lobbyists...

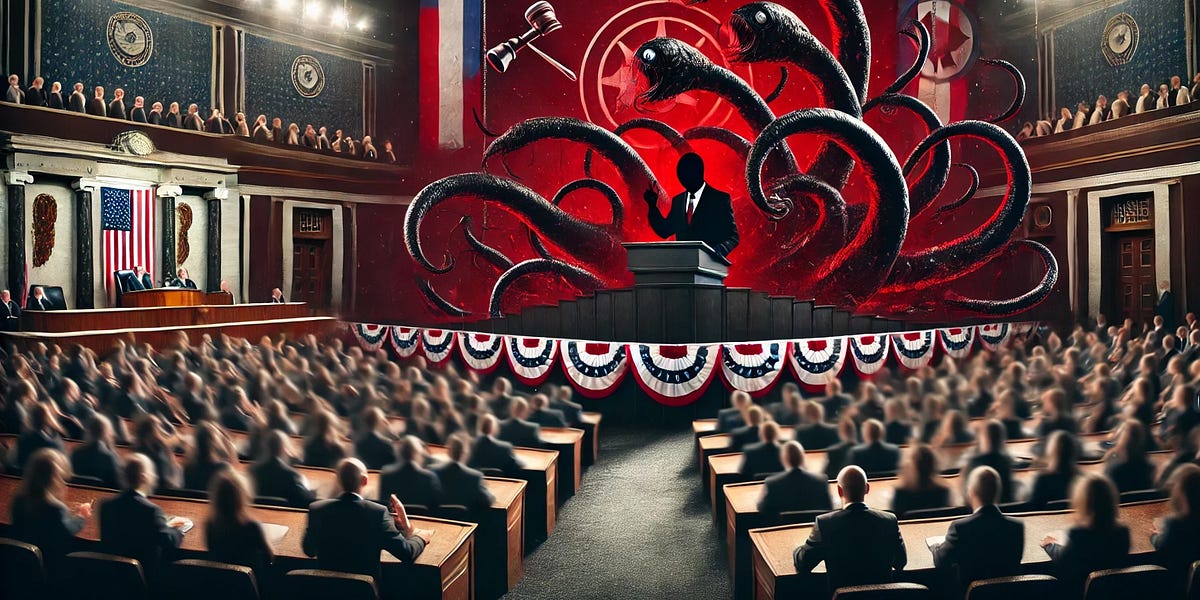

Elon Musk’s Privileged, Racist Roots

“I took them to school in the Rolls Royce most of the time.”

Meet the Project 2025 People Who Are Filling Up Trump’s Administration

Trump denied any ties to Project 2025 but these 10 appointments prove he was lying.

we HAD something along those lines, but our "Supreme" court ruled that mega-rich corporations were "people" that had rights as well. Congress (mostly) isn't sympathetic, understandably, since they get a large (all!) cut of the cash....It would also be interesting to be able to limit private funding to political parties by individuals/companies/organisations, which could then act as lobbyists...

"exoneration" is a matter of conscience for many. if they (he) believe he was exonerated, then he was...in their opinion.

Trump’s Monsters’ Playbook: Lies, Fear, and the Cult of Dehumanization

This is exactly the sort of environment which can turn normal people into monsters who then seize control and ultimately destroy nations from within…

sounds a lot like Germany during the 1930s, doesn't it?

Trump’s Monsters’ Playbook: Lies, Fear, and the Cult of Dehumanization

This is exactly the sort of environment which can turn normal people into monsters who then seize control and ultimately destroy nations from within…hartmannreport.com

well corp's are owned by 'people' .... i guess how the judges looked at it...we HAD something along those lines, but our "Supreme" court ruled that mega-rich corporations were "people" that had rights as well. Congress (mostly) isn't sympathetic, understandably, since they get a large (all!) cut of the cash.

Errol Musk also has a child that he had with his stepdaughter who he helped raise from the age of 4 when he was in his 70's and she was in her 30's. These people are pure filth.

“The Elon”: How a Nazi Rocket Scientist Invented the World’s Richest Man

Errol Musk named his son after a character in a sci-fi book by the inventor of the V-2 Rocket, Wernher von Braunwww.mind-war.com

Like Father Like Son: Elon Musk's Dad Has Secret Second Kid With Stepdaughter

Elon Musk's father Errol revealed that he had a second child with his stepdaughter Jana — and explained why he'd have more kids.

sounds a lot like Germany during the 1930s, doesn't it ?

In as much as each was financed by the same source, yes it surely does.

Eltitoguay

Well-known member

Post in thread 'commies' :

A party founded by Nazi leaders after World War II, about to govern Austria for the first time.

Austria opens the door to the heirs of Nazism.

https://www.icmag.com/threads/commies.17797147/post-18878462

Last edited:

What Will Be the Impact of Social Media Plunging Us Further into a Post-Truth Crisis?

Why Zuckerberg’s changes at Meta signal a darker future for Democracy...

The Rise of Trump’s Thugs?

Trump has long admired dictators who weaponize civilian gangs to crush dissent. Will his next chapter involve unleashing his own militias to terrorize the American public?

wrong... the last 4years we have been in darkness.... now i see the lightWe are seeing a global resurgence of right wing power structures,

long in the works by forces which redefine the concept of dark.