acespicoli

Well-known member

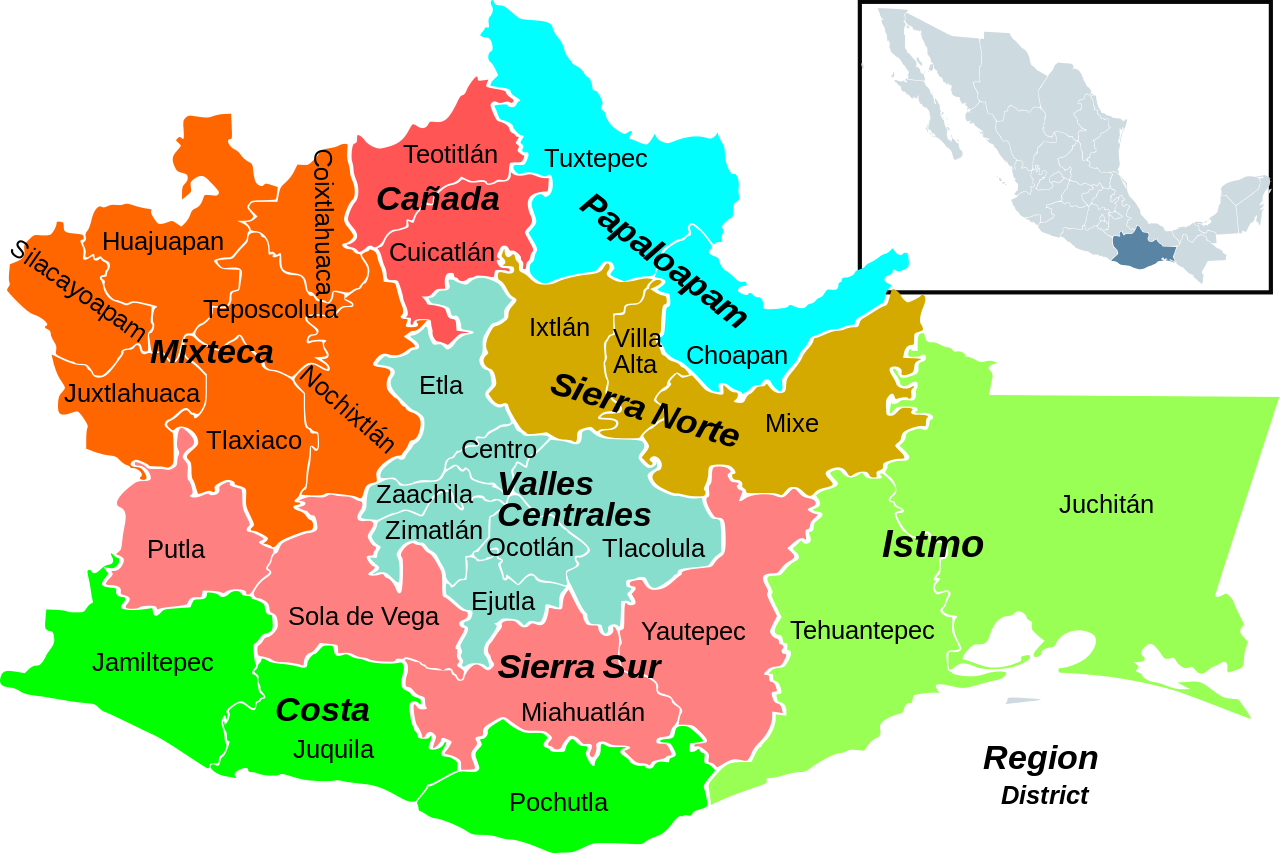

Oaxacan Landraces the land the people the history the plants

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

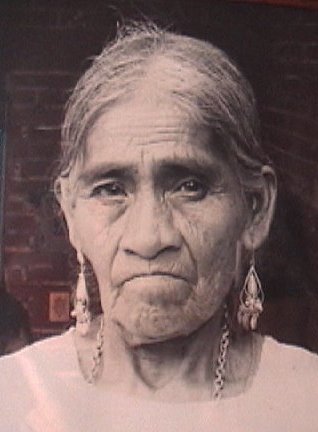

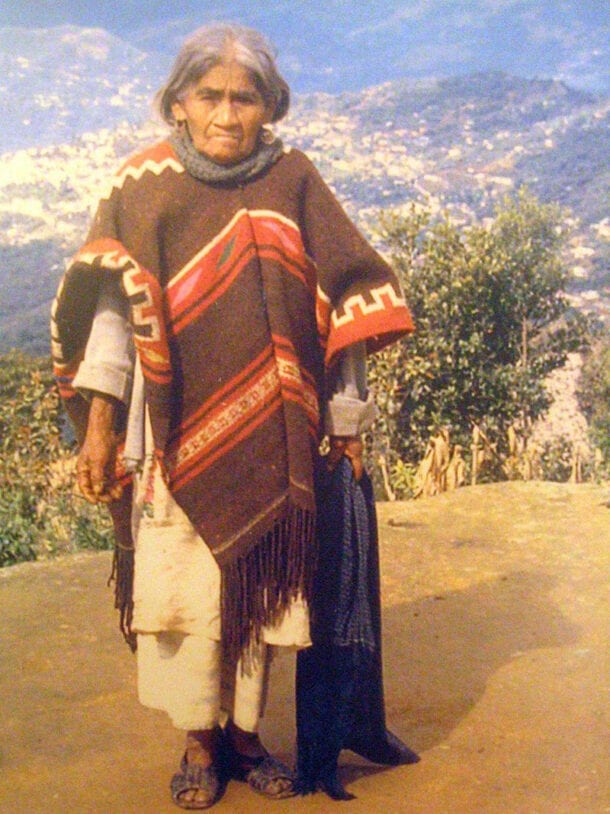

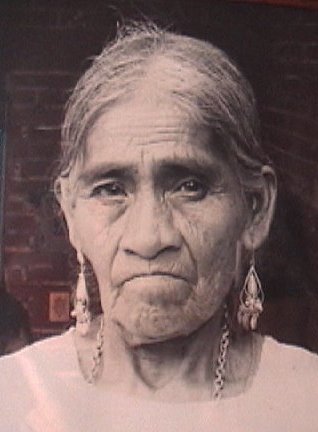

María Sabina

Mar 17 (Jul 22), 1894 - Nov 22, 1985

Summary

María Sabina was the Mazatec curandera from Oaxaca, Mexico who encountered R. Gordon Wasson on his trip to Mexico in 1955. On June 19th, 1955 she introduced him to psilocybin mushrooms during a healing ceremony. He became the first Westerner to experience the effects of these psychedelic fungi, followed shortly thereafter by Valentina Wasson. Wasson wrote about his experience with María and the psilocybin mushrooms in an article for Life Magazine in 1957.

In the Life Magazine article, Wasson referred to María Sabina as "Eva Mendez" in an attempt to protect her privacy, but the attempt failed. Over the coming years, María Sabina was inundated with visitors from the United States. The onslaught of "young people with long hair who came in search of God" disrupted her village and led to her arrest on more than one occasion by local federales. She sometimes turned visitors away, and sometimes introduced them to the mushrooms they sought, occasionally charging a fee, and often not.

María Sabina died in 1985 at the age of 91.

Books

María Sabina is regarded as a sacred figure in Huautla and considered one of Mexico’s greatest poets.

She did not take credit for her poetry; the mushrooms spoke through her:

Codex Vindobonensis Mexicanus

Pictographic representation of the first dawn

Cure yourself with the light of the sun and the rays of the moon.

With the sound of the river and the waterfall.

With the swaying of the sea and the fluttering of birds.

Heal yourself with mint, with neem and eucalyptus.

Sweeten yourself with lavender, rosemary, and chamomile.

Hug yourself with the cocoa bean and a touch of cinnamon.

Put love in tea instead of sugar, and take it looking at the stars.

Heal yourself with the kisses that the wind gives you and the hugs of the rain.

Get strong with bare feet on the ground and with everything that is born from it.

Get smarter every day by listening to your intuition, looking at the world with the eye of your forehead.

Jump, dance, sing, so that you live happier.

Heal yourself, with beautiful love, and always remember: you are the medicine.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

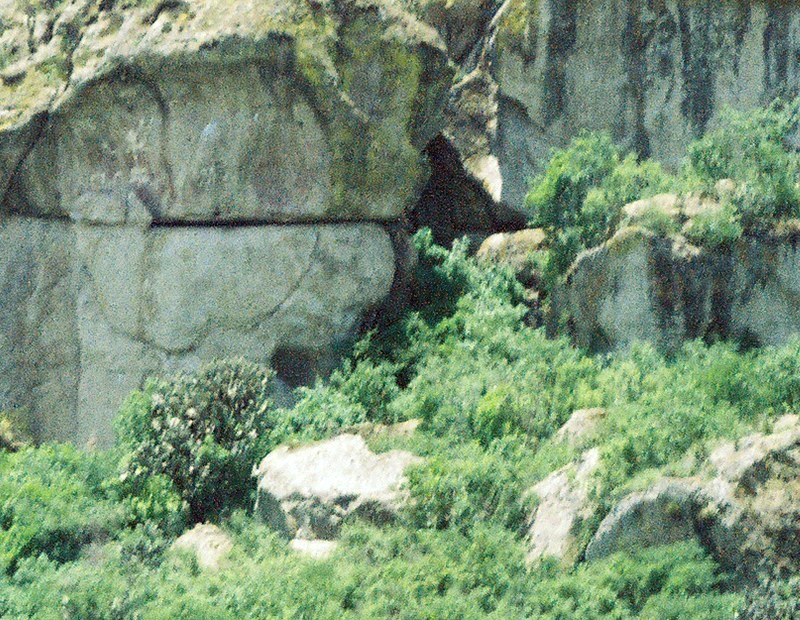

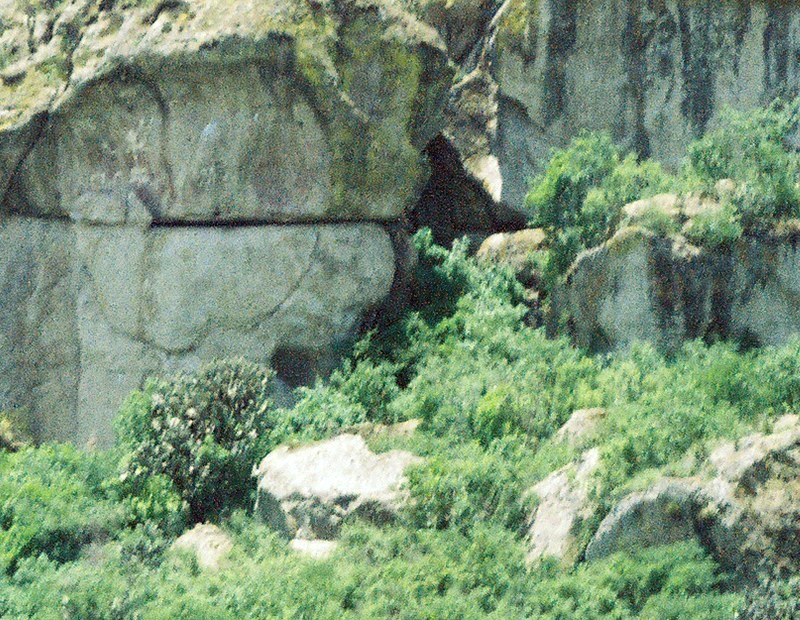

Guilá Naquitz Cave in Oaxaca, Mexico, is the site of early domestication of several food crops, including teosinte (an ancestor of maize),[1] squash from the genus Cucurbita, bottle gourds (Lagenaria siceraria), and beans.[2][3][4][5] This site is the location of the earliest known evidence for domestication of any crop on the continent, Cucurbita pepo, as well as the earliest known domestication of maize.[6]

Macrofossil evidence for both crops is present in the cave. However, in the case of maize, pollen studies and geographical distribution of modern maize suggests that maize was domesticated in another region of Mexico.[7]

www.tradewindsfruit.com

www.tradewindsfruit.com

theeyehuatulco.com

Mole Verde Recipe of Esperanza Chavarría Blando (reproduced with permission of her estate)

theeyehuatulco.com

Mole Verde Recipe of Esperanza Chavarría Blando (reproduced with permission of her estate)

is a nationally renowned Oaxacan chef

www.savoryspiceshop.com

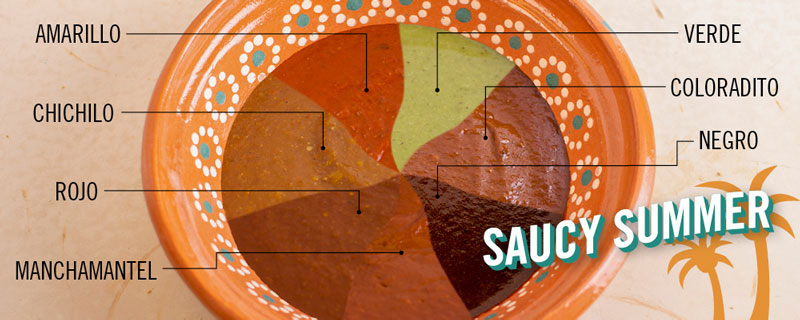

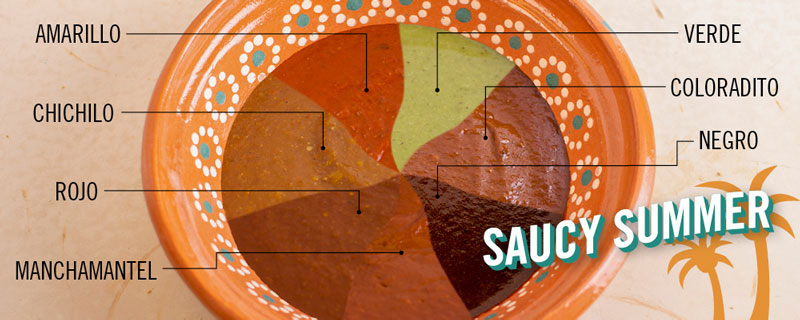

Puebla is generally regarded as the birthplace of mole but Oaxaca has claimed seven mole babies as its own: rojo, coloradito, amarillo, verde, negro, chichilo, and manchamantel.

www.savoryspiceshop.com

Puebla is generally regarded as the birthplace of mole but Oaxaca has claimed seven mole babies as its own: rojo, coloradito, amarillo, verde, negro, chichilo, and manchamantel.

message me if youd like to borrow this great cookbook

Photo by Kagyu

Oaxaca - Wikipedia

María Sabina - Wikipedia

“I am wise even from within the womb of my mother. I am the woman of the winds, of the water, of the paths, because I am known in heaven, because I am a doctor woman.”

– María Sabina Magdalena García

María Sabina was a Mazatec sabia (“one who knows”) or curandera (medicine woman), who lived in Huautla de Jiménez, a town in the Sierra Mazateca area of the Mexican state of Oaxaca in southern Mexico. She spent her entire life in that small village up in the mountains and worked the landMaría Sabina

Mar 17 (Jul 22), 1894 - Nov 22, 1985

Summary

María Sabina was the Mazatec curandera from Oaxaca, Mexico who encountered R. Gordon Wasson on his trip to Mexico in 1955. On June 19th, 1955 she introduced him to psilocybin mushrooms during a healing ceremony. He became the first Westerner to experience the effects of these psychedelic fungi, followed shortly thereafter by Valentina Wasson. Wasson wrote about his experience with María and the psilocybin mushrooms in an article for Life Magazine in 1957.

In the Life Magazine article, Wasson referred to María Sabina as "Eva Mendez" in an attempt to protect her privacy, but the attempt failed. Over the coming years, María Sabina was inundated with visitors from the United States. The onslaught of "young people with long hair who came in search of God" disrupted her village and led to her arrest on more than one occasion by local federales. She sometimes turned visitors away, and sometimes introduced them to the mushrooms they sought, occasionally charging a fee, and often not.

María Sabina died in 1985 at the age of 91.

Books

- María Sabina: Selections, by J. Rothenberg (2003)

- María Sabina, Her Life and Chants, by Álvaro Estrada (1981)

- Vida de María Sabina: la sabia de los hongos, by Álvaro Estrada (1977) (español)

- María Sabina and her Mazatec Mushroom Valeda, by Wasson, Cowan, Cowan, & Rhodes (1974)

- Conversaciones con María Sabina, by Enrique González Rubio (1992) (español)

- María Sabina: Saint Mother of the Sacred Mushrooms (1997)

- The Mazatec Indians: The Mushrooms Speak

- Re-Reading María Sabina, by H.Yépez

- Clock Woman In The Land Of Mixed Feelings, by H. Yépez

- Account of Mushroom Healing Ritual with María Sabina

- Mushroom Healing Quotes

- Mushroom Pioneers, by John W. Allen

María Sabina is regarded as a sacred figure in Huautla and considered one of Mexico’s greatest poets.

She did not take credit for her poetry; the mushrooms spoke through her:

Codex Vindobonensis Mexicanus

Pictographic representation of the first dawn

Cure yourself with the light of the sun and the rays of the moon.

With the sound of the river and the waterfall.

With the swaying of the sea and the fluttering of birds.

Heal yourself with mint, with neem and eucalyptus.

Sweeten yourself with lavender, rosemary, and chamomile.

Hug yourself with the cocoa bean and a touch of cinnamon.

Put love in tea instead of sugar, and take it looking at the stars.

Heal yourself with the kisses that the wind gives you and the hugs of the rain.

Get strong with bare feet on the ground and with everything that is born from it.

Get smarter every day by listening to your intuition, looking at the world with the eye of your forehead.

Jump, dance, sing, so that you live happier.

Heal yourself, with beautiful love, and always remember: you are the medicine.

Guilá Naquitz Cave - Wikipedia

Guilá Naquitz Cave in Oaxaca, Mexico, is the site of early domestication of several food crops, including teosinte (an ancestor of maize),[1] squash from the genus Cucurbita, bottle gourds (Lagenaria siceraria), and beans.[2][3][4][5] This site is the location of the earliest known evidence for domestication of any crop on the continent, Cucurbita pepo, as well as the earliest known domestication of maize.[6]

Macrofossil evidence for both crops is present in the cave. However, in the case of maize, pollen studies and geographical distribution of modern maize suggests that maize was domesticated in another region of Mexico.[7]

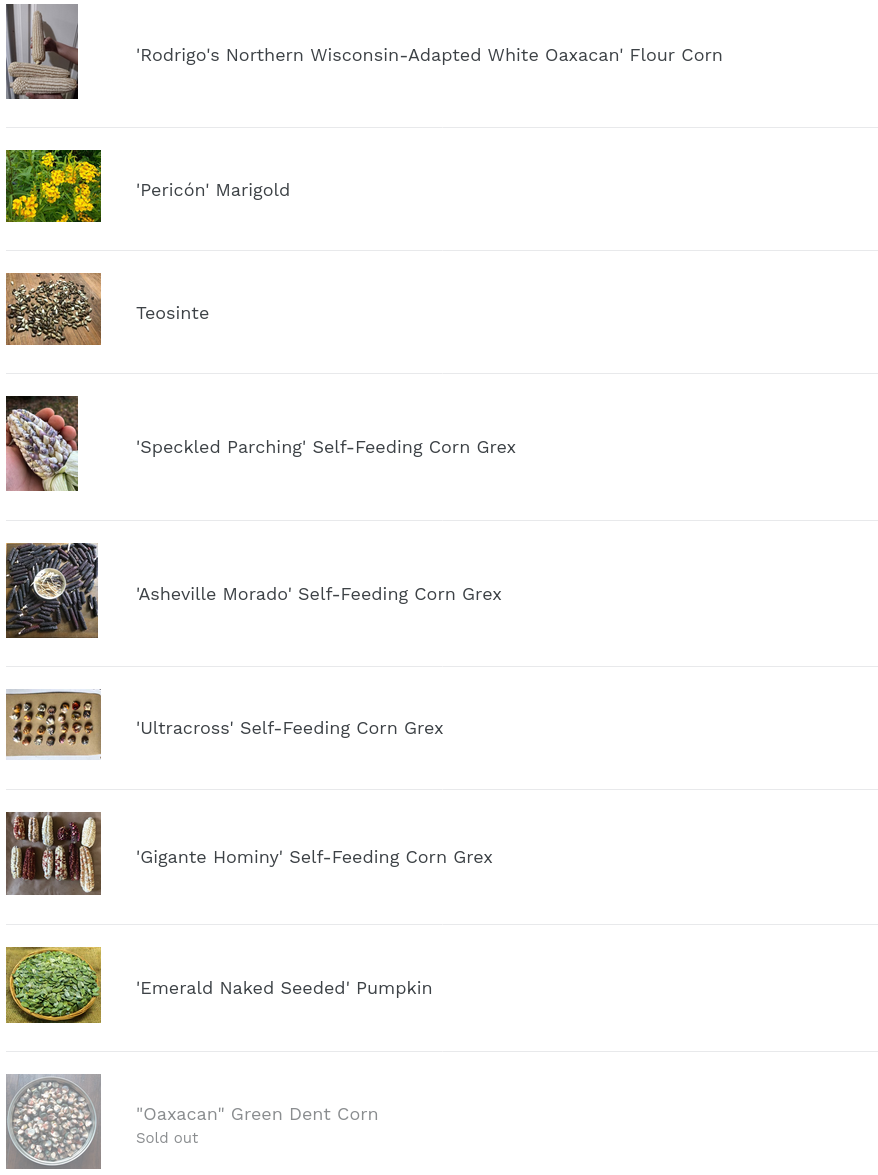

Trade Winds Fruit

Huge selection of rare and heirloom seeds perfect for any climate. Over 1500 varieties of peppers, tomatoes, vegetables, heirlooms, tropical fruits and ornamentals.

Oaxacan Green Corn Seed Emerald green kernels for cornmeal Dent Corn

Oaxaca’s Traditional Mole Verde

By Alvin Starkman, M.A., J.D. The seven moles of Oaxaca is a fiction, but it is an effective means of marketing Oaxacan cuisine and gastronomic tradition. While mole verde is indeed one of the purp…

theeyehuatulco.com

theeyehuatulco.com

is a nationally renowned Oaxacan chef

Making the 7 Moles of Oaxaca in 7 Days: A Survivor’s Guide

It’s pronounced “moal-ay” (sorry not sorry if you read that whole first paragraph thinking small, sightless rodents had taken over the Savory Spice Test Kitchen). The word literally means “sauce”. Key cooking methods and ingredients distinguish moles from other sauces, but this subcategory is...

message me if youd like to borrow this great cookbook

Photo by Kagyu

Attachments

Last edited: